|

19th National Convention in Colombo today:

SLFP in contemporary politics of Sri Lanka

by Prof. Wiswa WARNAPALA

The

19th National Convention of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), which is

scheduled for today, coincides with the 57th anniversary of the party

which, founded in 1951, emerged as the most effective and formidable

alternative to the United National Party (UNP) which dominated the

political life of the country in the first decade of post-independent

Sri Lanka. The formation of the SLFP was a historic need as the people,

who suffered under colonialism and under the leadership of the

Senanayake regime, wanted an alternative political party to represent

their interests and grievances. The

19th National Convention of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), which is

scheduled for today, coincides with the 57th anniversary of the party

which, founded in 1951, emerged as the most effective and formidable

alternative to the United National Party (UNP) which dominated the

political life of the country in the first decade of post-independent

Sri Lanka. The formation of the SLFP was a historic need as the people,

who suffered under colonialism and under the leadership of the

Senanayake regime, wanted an alternative political party to represent

their interests and grievances.

|

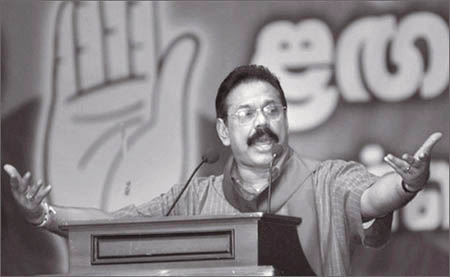

President Mahinda Rajapaksa addressing the SLFP Convention of

2007 |

The people, especially those of rural Sri Lanka, who remained

marginalised during the period of colonial domination, needed a

political party which can successfully aggregate the varied interests of

the people in the rural areas who, in the course of time, became the

arbiters of the national political conflict in the country. The late

S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, who, from the time he entered the political arena

in the country and through the State Council, engineered the

construction of a number of institutions through which he intended to

mobilise the oppressed and the emerging rural intelligentsia. It was on

the basis of the political potential of those forces and institutions

which had an exclusive traditional character that he identified the

historic foundations of the party, which, in 1956, came to be associated

with the “Pancha Maha Balavegaya” which constructed both the historical

and the ideological foundations of the party which, to a great extent,

looked at the major issues of the day from the point of view of

nationalism.

The “Pancha Maha Balavegaya” represented the major traditional

institutions in Sri Lanka, and they were vital instruments of political

change; the mobilisation of those with nationalist demands created a

strong popular base for the party which, due to the continued influence

of those forces, was expected to remain loyal to its traditional support

base and its historical foundations. Over time, it became a major

political resource of the party and its utilisation, in the context of a

growing awareness of the international factor, guided the major policies

of the party; its content, in a way, influenced the formulation of

public policy in a wide area of government activity. From that point of

view, the 1956 historic political change, based on the nationalist

political resources of the period, represented a major political

resource, though part of which remain politically invalid today, from

which the party, its main pressure groups and its widespread political

base derived immense political inspiration to convert the party into a

virtual political and social movement, the important features of which

nourished the party in the last fifty years. It’s still based on this

orientation.

Growing influence

The issue before the party, therefore, was how to come to terms with

the ever-growing influence of those traditional forces which derived

inspiration from both the history and culture of the country. At a later

stage, the question was what place, if any, was to be given the

traditional institutions, as these institutions and systems normally

have a powerful appeal to the masses and the SLFP understood its

potential as a source of power whereas the Marxist parties and others

saw this whole process as a form of political retardation. Much of the

politics of this period centred on this issue, and the continued

reliance on the forces and issues in the rural areas of the country,

helped the party to retain its formidable popular base, and all leaders,

irrespective of their standpoint on major issues of policy, were

expected to derive inspiration from this popular source of mass support.

As in 1956 and in the post-1956 period, the formulation of public

policy came to be stimulated by such political compulsions, many of

which were rooted in the traditional rural instruments of power. This,

in political terms, meant that the SLFP, from its inception, was a party

founded on the legitimate aspirations of the masses in the village, and

both the late S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and the late Sirimavo Bandaranaike

realising its tremendous impact on the whole process of political change

in the country, never deviated from this strategy which, till the

mid-seventies, determined the nature and content of public policy. Some

of the policy changes came to be determined by an ideology which

contained certain important strands of social democracy, and the

influence of the socialist ideology was not totally absent as this was a

period of socialist experiment in most countries of the third world.

All these countries, immediately after de-colonisation, began to

emulate certain features of the socialist experiment and the State-centred

development strategy came on the scene as the panacea for all ills in

the post-colonial State. Both economic and foreign policy came to be

built on those foundations which were partly ideological in character,

and this was inevitable as the trend in the post-colonial State in both

Asia and Africa advocated this direction in policy. Though angering the

West, it was a necessity for an emergent State to realise its objectives

and aspirations as an independent State, and the SLFP, as the political

party which enjoyed power in the Sri Lankan State on a number of

occasions, emulated this political strategy with a view to accelerating

the process of economic and social change on the basis of the legitimate

aspirations of the common man, whose interests and grievances, dominated

the policies of the party.

It was on the basis of such aspirations of the common man that the

SLFP’s historical foundations came to be built and any attempt to

deviate from such foundations interfered with its popular base. As long

as the party and its non-cosmopolitan leadership remained loyal to this

base, the party remained strong and continued to command respect among

the masses of the country.

Some regimes, which were formed under its leadership, were perceived

as “regimes of the common man”, whose improvement and enhancement of his

opportunities remained the basic policy-strategy of the SLFP, and all

rural reconstruction programs, enunciated in the ‘Mahinda Chintana’ and

put into practice through the main village reconstruction programs -

Gama Neguma, Maga Neguma, Jathika Saviya and Api Wawamu - are part of a

conscious policy strategy to address the burning issues of the rural

people, from whom the SLFP historically derives inspiration. The party,

from the very beginning, articulated the dynamism of the rural elite,

and unlike the UNP, never depended on the prowess of the

English-educated elite in Colombo. It was the over-reliance on the rural

intelligentsia which gave the party a solid base in the rural areas of

the country.

It was this formidable base which made the SLFP, despite internal

problems it experienced since the famous Kurunegala Conference in 1959,

became the most powerful political party with an illustrious record in

Government. All its Governments - the 1956, 1960, 1970 and 1994 regimes

and the present regime under the able leadership of President Mahinda

Rajapaksa, were regimes which made distinctive contributions to social

and economic development in the country.

The SLFP today has to play a leading role in the transformation of

the country; today the world is going through a period of

transformation. The SLFP, therefore, as the party of the people, needs

policy perspectives, based on its historical foundations, which take

cognisance of this transformation. President Mahinda Rajapaksa, as the

President of the SLFP, has understood the nature of this transformation,

and his policy package, based on his ‘Mahinda Chintana’, is a realistic

compendium of policies which could be utilised to bring about this

transformation, the main features of which need to be stability, peace

and development.

Harmony and understanding among the different communities are equally

important for the acceleration of economic development. It is in this

context that the issue of the legitimate aspirations of the minorities,

especially those of the Tamil community, arises and they need to be

addressed in such a way that the nature of the Sri Lankan State remains

unitary in character. It was the SLFP which gave the unitary character

of the State a constitutional status, and the party, though deviating a

bit in 2000, remained totally committed to the preservation of the

unitary character of the Sri Lankan State, and it is through absolute

commitment to the concept of the unitary State that sovereignty, unity

and territorial integrity of the Sri Lankan State could be preserved.

Coalitions

It was under the leadership of the SLFP that coalitions were formed

in this country, and a new coalition political culture came to be

inaugurated. It, in addition to the nature of political stability which

it nurtured in the system, gave certain smaller political parties the

opportunity to share political power. It created opportunities for

national integration; this kind of coalition political culture has had a

major impact on national politics, for which the SLFP, with the correct

political perceptions, provided leadership.In the area of foreign

policy, the SLFP historically took the lead in framing the right foreign

policy strategies for a new State which was emerging out of colonialism.

All post-colonial States had their own foreign policy postures, some

of which showed their alignment with certain powers. Sri Lanka, on the

other hand, gave expression to a kind of dynamic neutralism based on

national interests; it took regional interests too into consideration in

formulating the foreign policy, and the political and intellectual

inputs for the formation of this policy came from the SLFP, whose

leaders, both the late S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and Sirimavo Bandaranaike

made the most outstanding contribution.

In formulating foreign policy, the SLFP always thought in terms of

national interest, and President Mahinda Rajapaksa, in the last four

years, managed power as one of the ablest political managers of this

period, to see that foreign policy becomes an important element in the

management of political power in the context of a massive humanitarian

offensive to defeat the most sophisticated and brutal terrorist

organisation in the world.

The foreign policy calculations became fundamental and vital in such

operations, and the past record of the SLFP’s foreign policy, in the

most crucial period, came to the rescue.

Foreign policy

The foreign policy legacy of the fifties, sixties and the seventies

began to exert an influence, and Sri Lanka was seen as a small nation

which deserves international support to help it to crush terrorism of an

international dimension. The SLFP is the only political party in the

country which conducted a realistic and pragmatic foreign policy based

on national interests, and Mahinda Rajapaksa, in the last three years,

gave leadership to a foreign policy based primarily on pragmatic

considerations and it was on the basis of this policy that he sought the

assistance of new friends. A nation, when faced with a major internal

crisis, the main plank of which is to assault both national sovereignty

and territorial integrity, cannot bank on the friendship of traditional

friends alone. Pragmatic changes and adjustments, based on the immediate

national interest tied to the security of the State, are needed, and

President Mahinda Rajapaksa made one or two superb foreign policy moves

in the international arena with which he demonstrated his capacity for

bold policy initiatives.

As Henry Kissinger says, foreign policy always comes down to making

choices, and President Mahinda Rajapaksa made such choices at the

appropriate time, and established constructive relationships with

countries. It was an aspect of summit diplomacy. Relations with India

have been constructed on the basis of historical and geo-political

considerations and the SLFP, from inception, has made friendship with

India as one of the major elements in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy.

President Mahinda Rajapaksa, displaying his ability in handling major

foreign policy issues, managed the India factor and the Tamil Nadu

factor in an admirable way.In the context of a fundamental challenge to

the security of the Sri Lankan State, vital foreign policy adjustments

are necessary to meet the challenge, and it was in this scenario that

the SLFP took certain bold initiatives in the area of foreign policy.

This, again, was due to his bold policy initiatives, based on the

party’s historical foundations. He never gave into unwanted

international pressure.

He, with an unique and extraordinary charisma and popular acceptance,

has successfully obliterated all the names of the leaders of independent

Sri Lanka, and this is his unique and historic achievement which is

certain to remain alive in the minds of the people who saw the defeat of

the LTTE as a major historic achievement.

Individual leadership

According to Max Weber, “there is the authority of the extraordinary

and personal gift of grace, the absolutely personal devotion and

personal confidence in heroism and other qualities of individual

leadership. This is charismatic domination exercised in the field of

politics.”On the basis of Weber’s assessment, one can say that the

leader of the SLFP, President Rajapaksa, within a short period of time,

displayed effective qualities of individual leadership through which he

strengthened his own mass base which, in effect, has now become a major

challenge to all established political parties in the opposition.

How did he succeed in obliterating the names of all the leaders of

post-independent Sri Lanka? It was through his commitment and dedication

to the unity, sovereignty and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka and

this was primarily in the context of a massive challenge by the LTTE

which, according to many, was invincible. It was his firm belief in the

need to protect the unitary character of the Sri Lankan State which

motivated him to launch a humanitarian offensive to crush the LTTE, and

its demolition and the virtual annihilation brought in a massive fund of

political support which is a major political resource which, through its

integral relationship to ancient traditions and traditional symbols of

power and legitimation, is certain to provide him and his party with

many more such resources to strengthen himself and the party in power.

President Mahinda Rajapaksa, unlike all leaders who preceded him in

office, converted all the available traditional symbols of power and

instruments of legitimation, based in history and ancient political

lore, into very effective sources of aggregation of interests and

mobilisation of mass support. It was a kind of political strategy based

on a tradition - not an invented tradition - which can be described as

the careful reconstruction and renewal of an ancient tradition through

which a political resource has been unearthed to sustain himself in

power. He, on the basis of this resource, has now emerged as the most

outstanding leader whose position is unassailable and unchallenged

primarily because of the popular acceptance which he commands in the

country. It is an incomparable political achievement.

This special feature in relation to the political leadership in Sri

Lanka has had a tremendous impact on the political process, especially

within the parties in the political opposition in the country. The

Opposition, both inside and outside the legislature, is in total

disarray and is in steep decline; its support base has been damaged

beyond repair. As Harold Laski said, the Opposition, particularly the

Parliamentary Opposition does not know how to “bicker safely”.It does

not bicker at all and it engages only in cheap political rhetoric.

sTherefore President Mahinda Rajapaksa and the SLFP, with its tactics

and current strategies, have successfully engineered this crisis within

the main party in the Opposition whose support base has begun to erode.

All political parties in the Opposition are faced with a legitimacy

crisis where their membership has begun to desert the parties and join

the SLFP en masse because of the visible failure of their parties to

provide leadership to an effective alternative. This is a major crisis

within the ranks of the Opposition which specialises only on political

rhetoric instead of effective and efficient political strategies. The

growing rebellion within the UNP has weakened its leadership as well as

its popular base which has now begun to erode because of its failure to

understand its own role and its interests. Its leader cannot hide his

lack of authority within the UNP, and its political impotence is the

biggest advantage to the Coalition in power.

It, apart from its lack of cohesion, cannot generate new ideas, and

therefore, is in steep decline. The latest Provincial Council Elections

in Uva and the South amply demonstrate this fact, and the decline of the

UNP a permanent feature in the politics of the country, cannot be

arrested even with a change in its present leader.

Minority representation

The Coalitions, to which the SLFP provided leadership since 1956, are

an unique experience in the politics of Sri Lanka; the SLFP has

tactfully given places to all shades of minority representation. The

present coalition led by President Mahinda Rajapaksa is perhaps the only

government in post-independent Sri Lanka that accommodated such a

variety of minority interests.

All minority political parties remain fragmented and they have failed

to show their ability to work on the basis of a joint political agenda

and this again is due to their own regional and communal agenda. The

Government, at this point of time, has to perform a number of complex

functions that require continued governmental capability.

All functions of government, therefore, demand political capability,

and the SLFP and its leader, President Mahinda Rajapaksa have

endeavoured to develop a capacity to defend the territorial integrity of

the State, while taking calculated measures to sustain both internal

order and economic and social development.

The process of change, now taking place under the leadership of the

SLFP, is derived from such imperatives of governance, for which all

interests have to be carefully aggregated. This has been the main

achievement of this coalition government led by the SLFP, and this

particular strategy needs elaboration to understand the new processes of

change in Sri Lanka.

No party can remain in power without aggregating sufficient power

through the activation of individuals and groups who have power, and the

SLFP, with its experience in coalition politics, has successfully

mobilised the power of such groups to pursue its own political

objectives and purposes.

A leader needs certain political skills to manage power in a complex

situation, and it is the political resource which one commands that

gives the leader the opportunity to project an effective personalised

charismatic leadership as represented in the style of leadership of

President Rajapaksa who, through a unique kind of charisma, has put the

entire Opposition on the defensive.

The role and leadership of the SLFP, therefore, combines history,

tradition, ideology and personality, and the party has now emerged as

the most powerful political formation, which, given its solid popular

base in the Sri Lankan polity, is certain to remain the party of the

Government for a considerable length of time.

Through President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s personality, his style of

leadership and the wide popular acceptance which he still commands

within the polity, the party has obtained the kind of legitimacy which

it needs to remain in power.

It has not been acquired; it has been thrust upon the party on the

basis of a number of historic and contemporary political factors. SLFP,

as in its history of 57 years, has produced a leader to undertake yet

another historical mission on behalf of the party.

With the annihilation of the LTTE, which claimed invincibility for

more than three decades, a page in history has been turned by President

Mahinda Rajapaksa. The mere fact that this is so is enough to change the

vision of every politician and citizen in Sri Lanka.

(The writer is Minister of Higher Education)

|