|

Launch of the Lester James Peries and Sumitra Peries

Foundation:

Preserving cinematic legacy for posterity

By Ranga CHANDRARATHNE

The Lester James Peries and Sumithra Peries Foundation, was launched

recently in a simple but dignified ceremony at the BMICH. The ceremony

commenced with the welcome address by Trustee Yadamini Gunawardena (

Minister Dinesh Gunadardena’s son) outlining the objective of the

Foundation. The Lester James Peries and Sumithra Peries Foundation, was launched

recently in a simple but dignified ceremony at the BMICH. The ceremony

commenced with the welcome address by Trustee Yadamini Gunawardena (

Minister Dinesh Gunadardena’s son) outlining the objective of the

Foundation.

Apart from preserving the cinematic legacy of the doyen of Sri Lankan

cinema Dr. Lester James Peries and pioneer woman filmmaker and one time

Sri Lankan Ambassador in France Sumithra Peries, one of the cardinal

objectives of the foundation is to set up a ‘National Cinema Archives’

in Sri Lanka with the aim of preserving Sri Lanka’s cinematic legacy for

the future generation. Among the objectives are the promoting the art of

filmmaking and Children’s Cinema in Sri Lanka.

A message by President Mahinda Rajapaksa passing on good wishes to

Dr. Lester James Peries and Sumithra Peries and the Foundation was read

out by Ravindra Randeniya. The foundation’s official website WWW.

ljpfoundation.org was officially launched by Speaker Chamal Rajapaksa.

The Foundation was incorporated by an Act of Parliament and the proposal

for the Bill was made by Malini Fonseka and was seconded by J.R.P

Sooriyapperuma.

Indian filmmaker Padma Vibushan Dr. Adoor Gopalakrishnan, who is an

admirer of Dr. Lester James Peries and Sumithra Peries cinema, described

Dr. Lester James Peries as “a remarkable filmmaker – one of the greatest

living filmmakers in the world today"

In his remarks, Dr. Adoor Gopalakrishnan, stressed the need to set up

a ‘National Cinema Archives’ describing that "Both our countries are

blessed with humidity and heat which are the real enemies of films".

Dr. Lester James Peries oration

The focal point of the launch was the inaugural Dr.Lester James

Peries oration which was delivered by Prof. Wimal Dissanayake of the

University of Hawaii. In the oration, Prof. Wimal Dissanayake observed

,“Lester James Peries is unquestionably the greatest filmmaker that Sri

Lanka has produced. He is also among the greatest of Asian filmmakers.

His work can be approached profitably from diverse conceptual vantage

points . In this talk, my chosen conceptual vantage point that if the

social imaginary which opens a useful theoretical space for film

analysis.

|

|

Sumithra Peries |

The first Sinhala film ‘Broken Promise’ was made in 1947. This film,

directed by B.A.W. Jayamanne., was based in a stage play, had a great

impact on Sinhala audiences. He went on to direct a number of other

films that were based on stage plays. During the 64 years of its

existence, Sri Lankan cinema had made appreciable progress; it has had

its ups and downs.The recently concluded ethnic war, which lasted for

about three decades, severely and adversely impacted the local film

industry. Despite this, a number of Sri Lankan filmmakers went on to

make films that have won international acclaim. Among these filmmakers

Lester James Peries is the foremost; he is the doyen of Sri Lankan film

directors. He has received the highest honours bestowed on film

directors in India, France and Sri Lanka. Apart from Peries there are

other talented filmmakers such as Vasantha Obeyesekere, Dharmasena

Pathiraja, Sumithra Peries, Prasanna Vithanage, Asoka Handagama,

Vimukthi Jayasundera….”

One of the principal cultural theoretical theses that Prof.

Dissanayake who is an international expert on Asian Cinema, invoked was

cultural modernity. He pointed out that cinema served as both a

‘reflector and shaper of cultural modernity. “As we examine the growth

of cinema in Sri Lanka, one fact that emerges clearly is that from its

very inception it was associated with the question of cultural

modernity. Cinema is both a reflector and shaper of cultural modernity

in the island. During the four stages of expansion Sri Lankan cinema

manifested different interests and investments in confronting cultural

modernity.

Before we discuss how cultural modernity was captured in films, it is

important to describe what is meant by this term. Modernity signifies

not only cognitively understood categories such as science and

rationality but also values like secularism, individual freedom and a

sense of equality.

The way tradition inhabits modernity has to be teased out carefully

because the easy binary of tradition and modernity as polar opposites is

not borne out by the facts. Max Weber articulated the view that a

defining trait of modernity is the important emphasis placed on choice

as an aspect of one’s individuality. What is evident now is that the

question of choice is far more complex than Weber believed.

Social theorists saw modernization as a neo-evolutionary narrative

which pointed to a universal path that led to social development

(Weber,1947).. It was their firm conviction that there was only one

pathway towards modernity and it was the one that was traversed by

Europeans. However, the experience of developing societies has proved

otherwise. What has firmly being established is that there are many

modernities, and the velocity of the modernization process varies

considerably according to the culture of the society concerned.

Therefore, it is of the utmost importance that we talk in terms of

cultural modernities rather than discuss it as a monolithic term with

unambiguous meanings. This idea of cultural modernity is important

because it is precisely what we see in Sri Lankan films.

In the first phase of Sri Lankan cinema, questions of subjectivity,

clash between the individual and collectivity, which are marks of

modernisation were presented in culture-specific terms, often very

crudely. The second stage witnessed the spread of urban consciousness,

secularism, and scientific rationality as they impinged the local

culture. In the third stage, ideas of socialism, youth unrest, problems

of unemployment, alienation of youth, which were all inevitable

concomitants of the modernisation process, found cultural expression. In

the fourth phase, the ferocity of the ethnic conflict and its impact on,

and implications for, the state, civil society, rule of law and so on

began to be explored in terms of the vocabulary of local culture.

Therefore, it can legitimately said that during the fur sages of

development of Sri Lankan cinema, the idea of cultural modernity figured

very prominently. “

Citing Dr. Lester James Peries's trilogy of films Gamperaliya ( The

'Changing Village,') Kaliyugaya ( 'The Age of Kali') and Yugantaya ('The

End of an Era') , Prof. Dissanayake pointed that the person who made the

important conjunction between cultural modernity and social imaginary

was Dr. Lester James Peries. " .. a significant moment in the history of

Sri Lankan cinema, this idea of cultural modernity intersected with the

notion of the social imaginary in interesting ways.

|

|

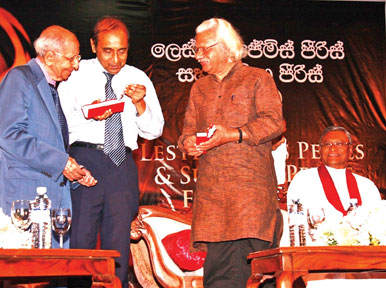

Dr. Lester James Peries, Dr. Adoor

Gopalakrishnan and Prof. Wimal Dissanayke at the launch |

This marks an important moment. The person responsible for the

conjunction is Lester James Peries. His trilogy of films The 'Changing

Village,' 'The Age of Kali' and 'The End of an Era', based on three

highly acclaimed novels by the foremost Sinhala novelist, Martin

Wickremasinghe. precipitated this moment. With 'Line of Destiny', Peries

inaugurated the art cinema in Sri Lanka; it constituted a formidable

challenge to the existing and bemused film culture, such as it was.

However, it is with 'The Changing Village' (Gamperaliya) that he found a

perfect concordance between the chosen experience and the desired supple

form leading to a cogent lyrical poise.

While 'The Line of Destiny 'represented, in terms of cinematic art, a

bold attempt to transcend the formula-guided cinema that was prevalent

at the time, the experience itself did not carry complete conviction for

me as some one who was born and bred in a remote village ( similar to

the one depicted in the film); things did not quite add up. However,

with the production of 'The Changing Village' (Gamperaliya), 'The Age Of

Kali' (Kaliyugaya) and The End of an Era' (Yuganthaya,) Lester James

Peries was able to fashion a cinema that was experientially authentic,

that carried the requisite social density and cultural modulation of

meaning and that carved out a concomitant cinematic poetics and

representational strategies for achieving his artistic ambitions. While

Nidhanaya, (TheTreasure) in my judgment, is Peries' most accomplished

work in terms of willed cinematic art, and Wekanda Walauwa (Mansion by

the Lake) is replete with Chekhovian visual symbolism, in this short

essay I wish to focus on The 'Changing Village', 'The Age of Kali' and

'The End of an Era', made in 1963,1983, 1985, respectively as

representing Peries' first measured attempt to explore the indigenous

social imaginary in terms of cinematography.; his cinematic fingerprints

are unmistakably present in these works.

Indeed, it was 'The Changing Village' that captured most powerfully

the birth of this moment. In response to these films, Peries found, what

most conscientious filmmakers are incessantly looking for - the supreme

spectator with discernment.

The term social imaginary has been put into wide academic circulation

by the eminent philosopher Charles Taylor.(Taylor 2004). This is indeed

a concept that I have deployed productively in some of my books on

cinema. As Taylor remarked, the concept of the social imaginary

encompasses something much wider and deeper than analytical schemes and

intellectual categories that scholars are in the habit of pressing into

service in there investigations.

He calls attention to the 'ways in which they (people) imagine their

social existence, how they fit together with others, how things go on

between them and their fellows, the expectations which are normally met,

and the deeper normative notions and images which underlie these

expectations.' Here, it is evident, that Taylor is focusing very

insistently on the existential and experiential dimensions of social

living. "

In the final analysis of Dr. Lester James Peries' cinema, Prof.

Dissanayake drew home the point that 'realism' for Dr. Peries is not a

mere 'mimetic reflectionism' but 'a poetic recreation and cinematic

re-coding', "Lester James Peries' attempt to capture the social

imaginary of Sri Lanka is that it is buttressed by his deep conviction

of the efficacy of cinematic realism and the importance of humanism as a

functional creed.

Realism, for him, is not merely a form of mimetic reflectionism but a

poetic re-creation, cinematic re-coding, of social reality where the

locus of meaning shifts to history and its inflections of human lives.

What Peries has sought to re-create in this trilogy of films is not raw

verisimilitude but poetic verisimilitude.

Peries, in my judgment, sought to go beyond the kind of realism

valorized by film theorists such as Andre Bazin, (Bazin, 1967) who urged

the importance of films as a neutral medium for recording natural and

cultural phenomena and viewed with great suspicion on the efforts if a

filmmaker at authorial intervention. Lester James Peries, on the other

hand, while recognizing the importance of verisimilitude also underlined

the significance of codes and conventions, both cinematic and cultural,

and the creative powers of the filmmaker in modulating reality and

giving it a sharper definition. The eminent film critic, Siegfried

Kracauer (1960) once remarked that, 'the cinema can be defined as a

medium particularly equipped to promote the redemption of physical

reality.'

|

|

Sumithra Peries |

This is precisely what Peries intended to do. He wanted his created

cinematic images to be true to Sri Lankan life and society; at the same

time, he wanted them to shine with a modulated lyricism. Similarly,

humanism, in his judgment, is not merely a mind-set but also a mode of

feeling and a part of his representational arsenal. His decision to

select three critically acclaimed Sinhala novels for cinematic

representation, his poetic lyricism, and sensitivity to indigenous

cultures on the move enable him to create three works of cinematic art

that resonated with the social imaginary of the people. "

Dr. Lester James Peries as a pioneer filmmaker

The launch of the Dr. Lester James Peries and Sumithra Peries also

marked the Diamond Jubilee of winning the first-ever international award

in 1951. It was 'The Mioni Cinema Challenge Cup' presented to Dr. Lester

James Peries by the British Government for 'Soliloquy'. The launching of

foundation also marked a half a century for Sumithra Peries's brilliant

career in cinema. She joined Dr. Lester James Peries in 'Sandeshaya' as

an assistant director.

Looking back on Dr. Lester James Peries's trailblazing career in

Sinhala cinema and the evolution of Sinhala cinema from studio-shot

formula films to artistic films of international repute, what is obvious

is that it is Dr. Peries's pioneering attempt with the production of

Rekawa that altered the course of Sinhala cinema. 'Gamperaliya' (Change

in the Village -1964) which has recently been restored is still

appreciated worldwide by diverse audiences. It is one of the instances

where a cinematic masterpiece was made based on a classic Sri Lankan

novel by Martin Wickramasinghe. Gamperaliya as a restores classic is

considered as one of the ten best films of the twentieth century.

'Nidhanaya', (The Treasure),a brilliant cinematic exploration into

the human psyche is not only a superb cinematic analysis of human psyche

but also a masterpiece of Sinhala cinema, marked for its mature

cinematic diction which is peerless in the annals of Sri Lankan cinema.

A significant facet of Dr. Peries's career in cinema is the sheer

diversity of his creations; 'Gamperaliya' is recognised for its

non-dramatic and realistic depiction of the village, 'Madol Duwa' (The

Enchanted Island -1976) may be evaluated for capturing the lives of

youthful escapade in a Southern coastal village. A living legend, Dr.

Lester James Peries is the only Sri Lankan filmmaker, who belongs to a

generation of legendary filmmakers such as Akira Kurasawa, Satyajith

Ray, Ingmar Bergman.

Sumitra as a pioneering woman filmmaker

Sumitra Peries is the path breaking Sri Lankan woman filmmaker who

paved way for the entry of women breaking the monopoly of then male

dominated Sinhalese cinema.

Looking at her remarkable career in cinema which bequeathed the

nation a corpus of creations including Gehenu Lamai (1977), Ganga Adara

( 1980), Yahalu Yeheli (1982), Maya (1984), Sagara Jalaya ( 1988) , Loku

Duwa ( 1996), Duwata Mawak Misa ( 1997- based on novel by G.B

Senanayake) and Sakman Maluwa ( 2003- based on a short story by Godfery

Gunatilake), Sumitra Peries stands out as a Sri Lankan filmmaker who

realistically depicted the Sri Lankan woman from diverse aspects.

The character of woman portrayed in her films is not a prototype or

stereotype woman often valarised by cultural puritans but the one who

plays a dynamic and significant role in life as a mother. For instance,

in her film Duwata Mawak Misa, Sumitra portrays the close relationship

between a mother and a daughter not only in Sri Lanka but also in any

Asian society.

Feminist issues

What is noteworthy is that her approach to dealing with feminist

issues is neither sympathetic nor clinical but a realistic one.

Her maturity in the craft was amply demonstrated in Yahaluwo (Best

friends) in 2007. The film was made at the tail end of the conflict and

masterly depicts the dynamics of ethnic relationships among diverse

ethnicities in Sri Lanka through the eyes of a child of mix parentage.

Yahaluwo is so far the most sensible cinematic exploration of diverse

ethnic relations in Sri Lankan polity as the sub-text of the film. At

the same time, it is also a children's film.

Study and exposure

|

|

A scene from

Gamparaliya |

One factor which makes Sumitra Peries is her deep understanding, vast

knowledge and experience in the field of cinema. It was in 1950s that

she studied film making at the London School of Film Technique and

earned a Diploma in Film Direction and Production (1957-1959).

Significantly she was the only woman student at the time and began

working at Mai Harris, a subtitling firm for a short spell.

Sumitra's brother Gamini contacted Lester and checked the possibility

of her sister to work with him.

Lester agreed and Sumitra started the work as assistant director in

his second film Sandesaya. A filmmaking company called Cinelanka was

established in 1963 with Anton Wickramasinghe also Lester and Sumitra as

major shareholders.

Apart from serving the nation in diverse capacities such being a

member of the Presidential Commission for two years to conduct an

inquiry into Sri Lanka's film sector, a member of the Board of

Management of the Institute of Aesthetique Studies, Kelaniya University,

Sri Lanka, Sumitra Peries was the Sri Lanka's Ambassador to France. She

won the award for the best film director in fifty (50) years of Sri

Lankan cinema.

|