|

Six Personal Investigations of the Act of Reading:

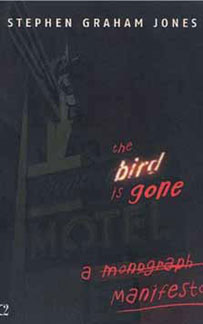

Stephen Graham Jones' The Bird is Gone : a manifesto

By Pablo D' Stair

|

Stephen Graham Jones

|

I've never been one to stop much during the act of reading-by this I

mean that unless (as they often do) some things come up to take me away

from a piece of writing I have sat down to go through, I read in an

unrelenting flow, one word, the next, the next-if there is a word I

don't recognize, I don't find a dictionary, if there is a name I don't

know how to pronounce, I just resort to acknowledging it visually, and

if I feel lost, if I for whatever reason miss a cue, don't exactly get a

firm grounding or sense of place, pace, situation etc. well...I just go

on.

***

I've always been of a mind that literature and the act of reading

literature is a particular interface meant to stimulate and jar loose

associations, the act is one of immersion, much the same as (in a lay

sense) I would listen to a piece of music-if I don't catch the chorus of

a rock-and-roll song, I don't rewind before the song is finished, pause,

squint my ears until I have it and if I don't quite get the import of a

ballad-love or murder-I don't, during the act of listening, find

secondary resources to help me understand peculiarities in word choice

or rhythmic progression.

And I am a lay reader-as much as I admire (and truly truly I do) a

scholarly reader and awe at what they do, much like I envy at what Glenn

Gould would hear when a quartet plays versus what I would, I nonetheless

embrace my philosophy of lay readership, finding it no less pertinent or

of import than its counterpoint.

***

Rather early on in Stephen Graham Jones' novel The Bird is gone: a

manifesto, there is a sequence where a character has ingested

hallucinogenic substances and the prose of the novel carries us along

with the viewpoint of this character, making no blatant distinguishing

between tangible reality and perceived reality-the

narcotic-sequence-of-events is as real and pertinent and banal as the

non-narcotic. Much in the way Celine could drift into a feverish

mindscape, navigate it, and tack out if it without needing a word to

note the shift in perception or a word to note the shift back, this

moment is where I first felt comfortable with Jones' novel-it's also the

first moment that made me wonder if my technique of reading forward with

no reversal was one that had an effect-and possibly a detrimental

effect-on my reading of the piece, or any piece.

|

What am I to do when confronted with a text that (and it seems at the

least blatantly if not flippantly, Jones' does this) eschews any call to

ordinary context, especially a text that, despite this dissociative

quality, seems to be telling a linear story-or, better to say, as is my

impression of Jones' work, "wants to be telling a linear story" (or

better still, a text that, while wholly nonlinear, "contains a linear

story")

Because, Bird is not a linear story in the same way that, for

example, The Trial is not a linear story-much as there is prose denoting

character, mood, opinion, and action, the very nature of "un-realitying"

the piece purposefully undertakes makes normal, human, interpersonal

narrative-connection completely non-essential, even ill fitting.

***

Or I thought so, at any rate. And in the many times my daily

activities took me away from the book, these thoughts took up some time

in my considerations-it could be said that these thoughts about the

nature-of-the-book became part-and-parcel to my experience-of-the-book.

Which is not, I wouldn't think, what the author intended (to use that

slightly ill phrase) and not what, generally, I intend.

My act of departing from the novel and returning, according to the

dictates of my life, is one that long ago (so much so it is

subconscious, now) I accepted-that's a flat fact, but it's also, I

realize, part of how I read. And it redoubles the difficulty of context

in a work like Jones', because the fragmented, self-consciously

constructed aspects of Bird stand precariously enough on their own

(stable, no doubt, but precarious) without the added cross to bear of a

reader (me) moving through them with no pause and then diving in every

three pages after being distracted, not even back peddling a paragraph

to get an idea "Where was I?"

***

Bird, to say a few words about it directly, is a novel that in both

plot-element and technique seems to me built upon the fascinating

premise that myth, folklore, arcane (and perhaps apocryphal) symbolic

identity and history is actually much easier and more tangibly grasped

than the nuance of the here-and-now. The here-and-now, flashing forward

two hundred, two thousand years, might as well be mythology and so it

seems that were the events of today described in a language akin to that

of myth, fable, poetic dreamscape, they would be equally as

unconsciously understood as an epic poem or piece of folklore from the

past-indeed, the sociopolitical context of the here-and-now would lose

bearing on matters just as that of ancient times does not influence a

casual understanding of stories originating there. But throughout Bird,

I found myself much more readily able to "understand" and "follow" the

abstract narratives introduced, those set outside of time and place-oral

legend, description of abstract, expressionist stage-play-than the story

set in the immediate present (a fictional future, to follow the conceit

of the novel) and this further made me conscious of how I behave as

reader.

Hadn't I ought to be taking some pains to interpret, rather than to

experience? The fact that I increasingly understood the work was not an

abstraction merely because of the circumstances of my having to read it

piecemeal, but was actually, purposefully a carefully constructed series

of (to my way of thinking) fever dream revelations, an "abstract on

purpose" seemed to be relevant, but I didn't care to interface with the

piece outside of my ordinary methods (or, perhaps I should say,

anti-methods).

***

Yet here: why would I say "carefully constructed"? Why this

assumption as a reader about the motivations or techniques of the

writer-motivations and techniques which, really, I should say I feel are

irrelevant?

***

I found the prose of the novel intelligent, cognizant of itself (even

at times arresting, beautiful) so from this I assumed there must've been

a schematic, some mathematic to decipher which could render the novel

"more ordinary" make the fact it was constructed and written with such

obvious avoidance of ordinary pattern-of-thought or narrative construct

nothing more than a fun-and-games, a personal indulgence of kink on the

part of the Jones.

But this is absurd. In the same way I could not say Bob Dylan's book

Tarantula-which I felt kin to Bird-was either calculated or

uncalculated, and couldn't (and certainly shouldn't) equate it to being

unconsidered gobbledygook, just something churned out willy-nilly

without reason merely because it seems pattern-less with regard to

generic "books", I could not say that Bird was either careful or

slapdash, purposeful or (even partially) random.

***

I will state bluntly that I think imagining or wanting context in

literature to come from the author is a pointless and irrelevant way to

experience it--this reduces art to chit-chat, reduces experience to

smiling at someone else's anecdote.

***

Do I, in fact, while I am reading think that what I read "wants me to

understand it"? Is understanding at all relevant to my experience as a

reader?

I've never found literature to be (or at least not primarily) a tool

for aiding understanding-in fact, the fever-dream sequence I considered

Bird, a writing that seemed unconcerned with itself except as expression

of mind-state, poetic, sequences-of-words that "fit-together" but meant

as little as they meant much, is something I find profoundly valuable in

reading, the act. To start a book (a pile of words) and to read them, in

sequence, regardless of whether anything is being consciously grasped is

a kind of sublime thing-much like when walking down the street I notice

only some microscopic portion of what there is yet say I know the

street, I think it is a misstep on the part of a reader to think that a

novel, merely because its order can be manipulated, can be reordered,

should be, and a bigger misstep to think the reordering is more

appropriate, or as appropriate, as letting the sequence lay.

A side-thought that kept cropping into my mind while reading Jones'

book was that sequence, in the end, is irrelevant, because the mind does

not remember things sequentially, however much it may receive input that

way. Indeed, I've often felt that it might be better to say "I watched a

book" than "I read it" -the same way one watching the performers of a

symphony orchestra or watching the specific colours of stage lighting

during a play is impactful and necessary-the way a book is watched,

under what circumstances, is as much a part of its necessary self, its

lived self, as the words, the craft, the thing.

***

Yet for all of my belief in a necessary disintegration of authorial

intent, intent-of-artwork, for all of my preferring to note my own

thought processes when confronting a piece rather than ponder the

theoretical thought processes of others, I still have to admit that I

have preferences and cannot talk my way out of them-I have preferences,

beliefs, and so my time with Bird brought up another question-Do I

consider it something I've read?

After all, if I listened to portions of a song, five seconds at a

time, over the course of a month, I would be in little position to say I

even knew what it "sounded like" let alone that I'd listened to it. In

fact, books, like music, I principally feel are built, intended,

needed-to-be read more than once. Certainly I could not think that

either Jones or (to be poetic a moment) the book itself would consider

someone who gave it a close, careful, sequential, investigative first

read in any better position to say they've read it than someone who read

it half-drunk and mad-dash if both parties only went through just the

once-going through pages slowly, keeping a notebook to assure myself of

X or Y or Z is not a way to any more make certain I have read

something-indeed, I would imagine with a piece such as Bird a

methodical, calculating reader would come away as much with a void on

them as I have.

***

The subject matter of what is read is irrelevant to the act of

reading-perhaps that is the quickest way to summarize here, and The Bird

is Gone: a manifesto, seems if not to embrace that (for who could ever

say that) but to represent it.

Jones seems to me to have rendered an instant folklore, something no

more understood than not, something to be hummed and made into separate

songs as much as the novel itself (in choice of section break and

typeface) makes itself so clearly built of components, shows all the

seams of the garment as part of the seamless whole. It's something of a

tradition-less folklore (or I think of it that way) an instantly old

story, bereft of specificity, left only to personal interaction and

interpretation-it's like something written in a lost language and

translated by guesswork, the party translating aware that all of the

important words lack context, lack the ability to be themselves-much the

same way an ancient might point smiling to a slumbering volcano to mean

"we have to be careful" but without knowledge of their worldview I might

just think they were pointing to a peaceful hill, tranquility, a symbol

of peace.

Pablo D'Stair is a writer of novels, shorts stories, and essays.

Founder of Brown Paper Publishing (which is closing its doors in 2012)

and co-founder of KUBOA (an independent press launching July 2011) he

also conducts the book-length dialogue series Predicate. His four

existential noir novellas (Kaspar Traulhaine, approximate; i poisoned

you; twelve ELEVEN thirteen; man standing behind) will be re-issued

through KUBOA as individual novella and in the collection they say the

owl was a baker's daughter: four existential noirs.

|