The sense of being between cultures

By Sunil Govinnage

“The sense of being between cultures `has been very, very strong for

me. I would say that’s the single strongest strand running through my

life: the fact that I am always in and out of things, and never really

of anything for very long.” Edward Said

Though Edward Said was born in Jerusalem (on November 1, 1935) due to

the wishes and choices of his parents as a child, Said lived "between

worlds" in roaming between Cairo and Jerusalem until he reached the age

of 12. At the age of 16, his parents sent him from Cairo to a

‘Puritanical’ boarding school where he began to broaden not only his

intellectual curiosity but also learning the art of music and developed

good skills as a pianist.

His movements between worlds have been a major issue that he had to

grapple with as a Palestine exile, and later as an American scholar and

intellectual, and above all, as a cultural critic who provided several

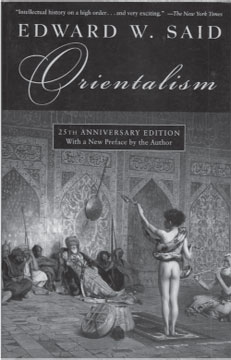

important theories including Orientalism, not only for his

contemporaries but for many emerging theorists and intellectuals who are

influenced by his work as tools to understand and analyse the world

around them exploring and expanding Said’s work on Orientalism, culture

and imperialism and many other theories he had left us with.

In the first instance, it was not his choice to select a life that

kept him moving between cultures. During an interview Said has

highlighted this issue: “... my father had American citizenship, and I

was by inheritance therefore American and Palestinian at the same time…” In the first instance, it was not his choice to select a life that

kept him moving between cultures. During an interview Said has

highlighted this issue: “... my father had American citizenship, and I

was by inheritance therefore American and Palestinian at the same time…”

Though the themes of feeling out of place, the meaning and the need

to live in interweaving cultures, and being far from ‘home’, affected

him significantly, and echoed throughout his brilliant academic and

private life. In this last article on the work and life of Edward Said,

I endeavour to look at his life between cultures.

Edward Said, Imperialist!

A Harvard trained right winger, Stanley Kurtz wrote in an article

titled ‘Edward Said, Imperialist -The hegemonic impulse of

post-colonialism (2001): “SAID’S HAS BEEN A LIFE of no fixed

attachments. Reared as a Christian by parents who were part Arab and

part American; educated in an elite British colonial boarding school

that forbade the use of Arabic; sent alone to the United States to

complete his education while still a youth, Said became a loner—out of

place in either America or the Middle East.

By the time he began his academic career, Said had been completely

Americanized, so Americanized that he held himself aloof from other Arab

immigrants. Yet his sense of being betwixt and between cultures—without

a real home—still burned.”

Despite such criticisms, it is important to understand (with similar

efforts invested to understand Said’s work on Orienatalism) why and what

Said has written on the theme of “Out of Place” and examine the

foundation for his thoughts behind his philosophy and outlook in this

regard.

Stanley Kurtz also believes that the basic premise of post-colonial

theory is that “it is immoral for a scholar to put his knowledge of

foreign languages and cultures at the service of American power” and

cites Edward Said's work in this area as most harmful.

However, other scholars who have also examined the issue that Said

had to live between cultures consider it as one of his strengths. Ramin

Jahanbegloo, a well-known Iranian-Canadian philosopher with a PhD in

philosophy from the Sorbonne writes: “Said’s conception of intellectual

thinking cannot, in this sense, be identified either with the liberal

tradition or with the claims advanced by a number of radicals. In this

sense, the trope of “outsiderhood” is a prominent one in Said’s life and

works. His childhood sense of being always ‘out of place’ as a

Palestinian exile, was never entirely lost, but was rather transformed

into a powerful intellectual spirit of criticism.”

Jahanbegloo adds further: “The idea of cultural border-crossing that

Said refers to should be considered not as a paradox of identity, but as

an indicative of the complex post-colonial and exilic consciousness. The

intensity of this exilic consciousness is exemplified in his book on

Palestine, After the last Sky, where he underlines: “Identity, who we

are, where we come from, what we are- is difficult to maintain in

exile…. We are the other.”

Said’s intellectual project is profoundly guided by this sense of

‘otherness’ or ‘outsiderhood’. Most of Said’s own works greatest

strengths and insights, results from this position of marginality where

he reflects on the intellectual advantages of being an outsider both his

native country and his domiciled USA.

Said’s sense of ‘outsiderhood’

Said’s great sense of ‘outsiderhood’ helped him to question the myths

and previously assumed perspectives through this outlook raising

questions such as “who we are, where we come from, what we are?”

informing the world what he believed in his book titled, Representations

of Intellectual as follows:

“[A]s an intellectual I present my concerns before an audience or

constituency. But this is not just a matter of how I articulate them,

but also of what I myself, as someone who is trying to advance the cause

of freedom and justice also represent. I say or write these things after

much reflection they are what I believe; and I also want to persuade

others of this view. There is therefore, this quite complicated mix

between the private and the public worlds, my own history, values,

writings and positions as they derive from my experiences, on the one

hand, and, on the other hand, how these enter into the social world

where people debate and make decisions about war and freedom and

justice.”

It is evident that Said’s firm belief on the role of Intellectual has

stemmed from a “mix between the private and the public worlds, [his] own

history, values…” suggest that his worldly perspective is a direct

result not only due to his ‘outsiderhood’, but also due to his living;

the sense of being between cultures is clearly comes out Said’s

insightful memoirs “Out of Place: Memories of Edward Said”. It may not

be considered a biography but a tedious meditation on his identity,

exile, and above all, a description of psychological scars of

dispossession.

This disposition that Said has articulated in words has also been

transformed into cinematic images based on his memoirs.

The film ‘Out of Place’ is a good mixture of Said's memoirs and other

key writings blended craft fully from readings of his work including

family home movies, dating back to 1947 adding a touch of personal

history. It also includes interviews with family who offer personal

reminiscences, Arab, Israeli and American thinkers, including many of

Said's colleagues and friends lan Pappe, Elias Khoury, Azmi Bishara,

Daniel Barenboim, Rashid Khalidi, Michel Warschawski, Noam Chomsky and

Dan Rabinowitz, among many others.

The film was directed by Sato Makoto and music score came from Daniel

Barenboim, the world renowned Israeli pianist and conductor, who took

Palestinian citizenship later in life.

The Japanese author, Oe Kenzaburo, the 1994 recipient of the Nobel

Prize for Literature wrote the following about the film:

"The serene, beautiful camera presses ever on through the landscape

of Edward Said's absence. The many folds of the pain of Palestine and

Israel are illumined. Said cuts across people's vibrant memories. And

Said's hopes appear above us."

As Kenzaburo points out, Edward Said’s enduring exile and the feeling

of dispossession along with his hopes and aspirations have kept him

going giving him the ability to “appear above us [others].”

The West-Eastern Divan Orchestra partnership

Edward Said’s partnership with conductor and pianist, Daniel

Barenboim brought about the West-Eastern Divan Workshop and Orchestra

(through the Barenboim-Said Foundation), promoted music and co-operation

through projects targeted at young Arabs and Israelis.

The West-Eastern Divan Orchestra was not a fantasy of social harmony

but was useful in addressing complex and hard political realities in

which it functioned.

Though now it is an international phenomenon, the orchestra began as

a small-scale series of music workshops. The workshops developed in 1999

to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Goethe’s birthcomprised chamber

music and was named the West-Eastern Divan was given,

As reported in the Jewish Quarterly, “[a]s part of Weimar's programme

of 'Cultural Capital of Europe' events, Barenboim was asked to establish

a workshop to bring together young musicians from across the Middle

East. With the support and enthusiasm of Edward Said, Barenboim invited

applications from young musicians from Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and

Israel. With the support and interest of Said, Barenboim invited

applications from players in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and Israel.

The response was overwhelming.”

Barenboim views the venture as creating a new and innovative channel

of communication and cooperation between assumed antagonists. Speaking

in his 2006 Reith lectures, Barenboim stated categorically that “the

orchestra cannot bring peace.” However, he suggested that it can ‘bring

understanding. It can awaken the curiosity, and then perhaps the

courage, to listen to the narrative of the other, and at the very least

accepts its legitimacy.’ Music, and specifically the orchestral

experience, is celebrated as the ideal vehicle for open interaction.

On describing a young Syrian and young Israeli musician sharing a

music stand, Barenboim stated: ‘they were trying to play the same note,

to play with the same dynamic, with the same stroke of the bow. They

were trying to do something together, something about which they both

cared… Well, having achieved that one note, they can’t look at each

other the same way, they have shared a common experience.’

Despite all the criticisms aimed at Edward Said by right wing critics

around the world form the USA to Australia, he had provided us with a

new philosophical framework and perspectives that could enlighten the

intellectual condition in today’s world and provided us with new

perspectives on our human world.

In 1994, three years after he was diagnosed with leukaemia, Said

started writing his memoirs, ‘Out of place.’ As articulated by him, it

“it is a record of an essentially lost or forgotten world.” He said:

“All families invent their parents and children, give each of them a

history, character, fate, and even a language. There was always

something wrong with how I was invented and meant to fit in with the

world of my parents and four sisters. Whether this was because I

constantly misread my part or because of some deep flaws in my being I

could not tell most of my early life... [I]t took me about fifty years

to become accustomed to, or more exactly to feel less uncomfortable

with…”

As he has articulated in his memoirs, most of his life Edward Said

felt, an urgency for intellectual exploration and resistance which

provided him with his new place whether it was the case in or look at

the issue of Palatine people’s struggle for their own sense of place.

Said’s discovery of his “new place” became an authentic space that

brought together all those who were struggling against all forms issues

about injustice and colonial authority.

In my understanding of Said’s work, he did form a unique approach;

the role of global public intellectual. Many of Edward Said’s admirers

and followers will continue to be inspired by his courage and many will

undoubtedly continue his journey by sharing and promoting what he

believed about the world around us. However, there is no doubt that his

death leaves a visible gap in public and intellectual life across the

world.

Edward Said died in 2003 after a decade-long battle with leukaemia.

(For

reader’s responses: [email protected])

|