|

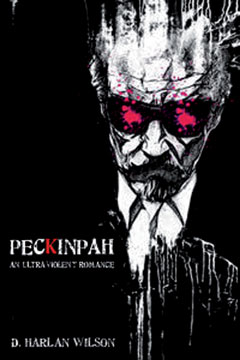

Six Personal Investigations of the Act of Reading:

Harlan Wilson's Peckinpah: an ultraviolent romance

By Pablo D'stair

The majority of the time I spent reading D. Harlan Wilson's

Peckinpah: an ultraviolent romance, I was involved in a mumbled debate

with myself about my feelings concerning the filmmaking Sam Peckinpah's

work, at least what I have seen of it. The primary reason for this is

because I have a very deeply felt and pondered take on the filmmaker and

the titular presence of his name-as well as textual references

throughout Wilson's book-seemed to suggest to me that an assessment of

some kind, a reflection on the filmmaker, was a necessary (or at least a

desired) touchstone, the name and all that could be attaché to it

something included by the author with a kind of pertinence.

|

|

D Harlan Wilson |

It is, of course, a disappointing trait about myself I have mentioned

elsewhere, the need to so overtly personalise my reading experience I

rather have to personalise the object and the content being read, then

if I fail to be able to synthesise the stimuli into some personal

version of expression I go blank. That is, I ask myself "What would the

meaning of this be had I written it? What would it take to get me to

write something 'like this'?" and all manner of solipsistic nevermind.

But, it's irrelevant to a piece of writing that I would not have

written it, as irrelevant as the content and opinions of the actual Sam

Peckinpah in relation to a cartoon scattershot of wordplay violence and

structural irreverence.

I got stuck with this book somewhere in the investigation of

referents, of the presence or lack of them, of the possible meanings of

them-the whole time thinking to myself there is no meaning to them. In

an odd way, it was the closest I feel I've honestly come to "just

reading" and the closeness to that I found off putting.

***

The "bizarro" or "irreal" nature of Wilson's book (these are both

terms I do not claim to understand beyond the suggestion of "weirdness")

of course suggested that no direct assessment of anything outside of the

pages would have bearing on that which was inside. Peckinpah, other than

a name and one neither mentioned gravely nor glibly, had nothing to do

with the text.

***

Honestly, I didn't know that the text had to do with anything, or

that anything had to do with the text-it struck me as a kind of

"novel-as-cartoon" heavily reliant on what (if visual) would have had a

peculiar zazz to it, but as a collection of words had more a ring of an

adolescent enthusiastically scribbling doodles on loose leaf or smoking

cigarettes and talking about celluloid imagery as though an adolescent

was who the filmmaker's were looking to dialogue with: the novel seemed

an enthusiasm crafted to be a "reaction object," the experience of it

lost the more an assessment of the particulars of the text was

attempted.

***

I guess I got to wondering about the confrontational nature of some

(all?) literature, and the relative nature of this confrontation-most

specifically, I read the book and spent time surrounding the read

wondering to myself whether I had ever felt "confronted," by this book

or any.

What did it mean to me, "to be confronted by a piece of literature"?

***

But, before I riff off in that direction, I should explain my basic,

superficial impressions of the work. Wilson takes the (at least

fractional) skeleton of what has become a rather typical story-type,

that of "absurd violence" being visited on an "innocent"

(if...questionable) town and its peoples, and during this torrent of

violence a "good man" loses "the woman he loves", and so is positioned

in the avenger role-the "villain" of the piece is cobbled up

gratuitously and a rather straightforward confrontation takes place in a

freeform, irreverent fashion.

That is, rather than humanistically flesh out this standard trope

(something I feel Peckinpah, the filmmaker,to harp on that, surely does)

Wilson dehumanises it through any means, reducing it to spectacle beyond

celluloid, beyond "over the top," seems to insist on keeping the world

fleshed only as far as pencil sketch, emotions treated as maybe some

thicker lines of ink here or there, focal points more than engines for

empathy or actual connection.

Which is not to say that something "other than humanity" is not

presented and presented hauntingly, something wholly impressionistic-a

terror, a void not meant to be personally contemplated but reduced to a

kind of cathartic gobbledygook, a kind of hell-of-observation never

being able to lead beneath a surface for the very fact that (the work

suggests) the world is nothing more than two dimensional dot-to-dot.

***

So, from this impression I initially found myself thinking that

confrontation, as I personally tend to consider it-an inner

confrontation, a reader confronted with thoughts of self, of human-ness,

a "forced or prodded contemplation"-was not present in any measure.

Instead, the confrontation was an affront to perspective, to the very

nature of accessibility, of dialogue, of meaning.

I rather liked the intricateness of how I read the book, the thoughts

it put in my mind (those doodlings in the margins of my own

schoolbooks)the prompt, the allowance of thinking of things only in

exaggeration, only as comic book. So I began to take the book as this

statement, and I began, in turn, to take its inclusion of Peckinpah as a

kind of rye, underhanded irony-to title a piece so devoid of measured,

felt, desired admission of the human condition after an artist (and to

mention him throughout) whose body of work is so rich with nuance and

almost neurotic attention to the interpersonal psychology of the

character's featured, seemed flippantly "on purpose," a glaringly,

almost angry way of bringing a reader into a consideration of how

Peckinpah and his workis often (and I feel wrongly) relegated to an

"expression of violence" or an "assault on the sensibilities of X era."

***

But of course, this would suggest that a familiarity-indeed, a

considered familiarity and particularised slant of Peckinpah's work-was

all but required, that the book would only with any gravity be speaking

to someone who...thought just like me.

And I doubted that.

Actually, I doubted it so much I read the work a second time, trying

to falsify my personality, to consider it as though it were a

celebration of a commonly held mindset, not something trying to get in

the face of anything else. Kind of a limp endeavoar, though, especially

as it lost the tension of the piece-for some reason I was still holding

onto the notion of labeling the piece confrontational, and somehow my

imagining it as a hearty celebratory thing just made it flatline.

***

MaybeI didn't feel confronted by the book, yet I could still paint it

as "confrontational." I do this all the time, in fact. I don't find

something flippant, but I say "it is clear that it wants to be flippant"

or I say "Well, I can think of people who would find it flippant, so it

must be aimed at them, so to speak"-the underlying idea always being

that my unruffled, perfectly-smooth-surface-response is kind of "where

it's at" that, in fact, to feel affronted is a mistake on the part of

someone else, a mistake I have overcome, somehow.

But certainly, there is something peculiar in labeling something

"edgy" if I don't feel any edge, in labeling something "absurd" if it

actually makes me nod inagreement-I wanted to call this book

confrontational because somewhere in me it was important to believe that

"confrontation," especially in literature, is something that somehow

stamps a badge of "quality" on a piece.

Now, I hate this thought, I hate that I think in anything close to

those terms.

So, I read through this bit and that bit of the book with it in mind

to think of something else, anything else.

***

It struck me as interesting that Wilson certainly did not shy from

what I'd go so far as labeling a traditional and linear storyline-all of

the flashes of difficult-to-pin-down excesses in the prose, all of the

departures from the status quo, so to speak, did nothing to carve out

anything particularly fresh, as far as I felt.

Now, I wondered what it was in me that figured something being

"irregular" in its descriptive properties should also eschew all

convention and this again drifted me back into my thoughts on Peckinpah,

the filmmaker. In fact, I wondered if I was even earnestly considering

my opinion or if I had gotten lost in a cycle of riffing-or worse, that

I was chasing my own tail, wanting to insist on some intrinsic desire to

communicate something through a literature, just getting bent out of

shape that a text seemed to be unconcerned with it-or more directly, I

wondered was I upset for some God unknown reason that the book wasn't

"my thing", didn't want to be "my thing" and so was forcefully insisting

on finding more and more elaborate ways to describe it, trying to own

it, trying to make it mine?

***

Except for the referents to its own exterior-the title suggesting

connection to something directly other than the text-I would think the

book was a statement meant for its own contemplation, and if not for

these exterior referents alsoso pointedly being brought interior,

sections of the text directly referencing not only the Peckinpah the

filmmaker, but his philosophy (or takes on his philosophy) I would have

thought of the book as a kind of punk rock riff for the sake of

immediate, superficial release.

Why the insistence on finding something to care about, when reading,

some line of argument, some interpretation? In other medium, really, I

am kind of against this-painting, photography, sculpture, whatever-and

certainly I never(even with literature) tend to put merit in anything

but "felt" response, yet with this piece by Wilson-though I felt things,

surely-my mind went every which way trying to intellectualise, trying to

treat it as a coded thesis.

It was a book I kind of felt I was dismantling, picking apart to

examine the pile of components with no real drive to reassemble once I'd

catalogued them-I just destroyed it and called that "reading".

***

And I somehow see nothing wrong with that.

Pablo D'Stair is a writer of novels, shorts stories, and essays.

Founder of Brown Paper Publishing (which is closing its doors in 2012)

and co-founder of KUBOA (an independent press launching July 2011) he

also conducts the book-length dialogue series Predicate. His four

existential noir novellas (KasparTraulhaine, approximate; i poisoned

you; twelve ELEVEN thirteen; man standing behind) will be re-issued

through KUBOA as individual novella and in the collection they say the

owl was a baker's daughter: four existential noirs.

|