Water striders do a balancing act on water!

If you have ever had the opportunity of closely observing the surface

of a pond, well, marsh or any calm body of water, you may have spotted

insects running, hopping or skimming along the water. What exactly these

creatures are and how they manage to walk on water may have baffled you.

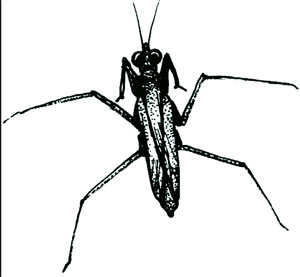

These large, long and slender-legged aquatic bugs are known as water

striders and you may be surprised to learn that they are perfectly

adapted to living on the surface of water and have the ability to

support and balance themselves nicely without sinking,

The creature is an arthropod (invertebrate with an exoskeleton, a

segmented body, and joined appendages; includes insects, arachnids and

crustaceans) and is also known as pond-skater, water-skater, water bug,

magic bug, skimmer, water scooter, water skeeter, water skimmer, water

skipper and water spider.

Water striders belong to a family known as Gerridae in the order

Hemiptera. Like all other insects, they have a body divided into three

segments (head, thorax and abdomen), six jointed legs and two antennae.

Its body is long, dark brown or black, and narrow. Some have wings while

others don't. Most water striders are over 0.5 inch (5 mm) long.

Scientists have identified over 1,700 species of gerrids, 10 percent of

which are marine (living in oceans) and are known as Halobates. Water

striders have two antennae with each divided into four segments. The

antennae have short, stiff bristles in the third segment. Relative

lengths of the antennae segments can help identify species within the

family Gerridae, but the first segment is generally longer and stockier

than the other three. The four segments combined are usually not longer

than the length of the strider's head.

The thorax, which is the section between the head and the abdomen, is

generally long and narrow. Some bodies are more cylindrical or rounder

than others. The outer layer of the thorax can be either shiny or dull

depending on the species, and covered with microhairs to help repel

water. The abdomen can have several segments.

Their short front legs are used to catch prey; the long, middle legs

act like paddles, moving the bug across the water surface, while the

long hind legs steer them and act as brakes. The front legs are attached

just behind the eyes while the middle legs are attached closer to the

back legs which attach mid-thorax, but extend beyond the terminal end of

the body. The specialised legs as well as their bodies are covered by

tiny water-repellent hairs called microsetae, with small nanogrooves and

it is this leg structure and their lightweight bodies that allow them to

stand on water, aided by the water's surface tension.The tiny hairs give

the water strider resistance to water, preventing drops of water from

weighing down the body.

Gerridae use the surface tension of water to their advantage through

their highly adapted long, strong and slender legs and weight

distributed over a larger surface area to stay afloat while the tiny

hairs on their bodies also provide a hydrophobic and larger surface area

to spread their weight over the water.

|

An adult water strider, *Gerris remigis**

*(WaterstriderOne) |

Striders can be seen making dimples or impressions with the ends of

their legs on the water surface. If their hair becomes wet due to oil or

detergent on the water surface, the surface tension would be broken and

the water strider will sink.Their legs also make them agile, helping

them to jump quickly to evade a predator or catch their prey. The

microsetae, which also cover the underside of their bodies, are also

used to detect vibrations in the water. If an insect accidentally falls

in the water, the water strider will feel it through the ripples the

insect makes in the water.

The water strider has very good vision and can move at speeds of 1.5

metres er second across the water surface, thereby grabbing its prey

quickly. It would push its mouthpart called rostrum into its prey and

pierce and suck the insect dry.

Its diet mainly consists of living and dead insects on the surface of

the water including aquatic insects such as mosquito larvae and land

insects, such as butterflies, dragonflies, beetles and worms and spiders

that accidentally land on the water surface or fall into the water.They

share the prey with other water striders around them. Halobates feed off

floating insects or zooplankton, and occasionally resort to eating their

own young. Cannibalism (eating their own kind) often occurs, but helps

control population sizes and restrict conflicting territories. Skaters

themselves become prey to predators such as birds and fish.

Their inability to detect any motion above or below the water's

surface is a disadvantage to them in this area. However, the fact that

they can move rather quickly on the water helps them escape predators.

They usually appear in large groups and prefer the protection of

overhanging trees and shade. Though they are found around water most of

the time, they fly far from the water to hibernate during winter,

returning to their watery homes with the onset of spring. In the

breeding season, water striders communicate by sending ripples to each

other on the surface of the water.

|

Close-up of a water striderís head |

Males generally produce ripples in the water under three main

frequencies: 25 Hz as a repel signal, 10 Hz as a threat signal, and 3 Hz

as a courtship signal. Females lay eggs at the water's edge, on stable

surfaces such as plant stems or stones, submerged in water. Halobates

often lay their eggs on floating ocean debris which are then spread

across the ocean. The amount of eggs laid depends on the amount of food

available to the mother during the season. They will reproduce

throughout the year in warm tropical regions, but only during warm

months in seasonal habitats.

Life cycle

Gerrids go through the egg stage and five instar (a stage of

development in arthropods) stages of nymphal (immature insects which

resemble the adult in basic appearance) forms before reaching the adult

stage. Individuals tend to develop at the same rate through each instar

stage.

|

Close-up of a water striderís head |

Each nymphal stage lasts 7-10 days and the water strider moults,

shedding its old cuticle. Nympths are similar to adults in behaviour and

diet, but are smaller (1mm long) and paler. It takes 60 to 70 days for a

water strider to reach adulthood, depending on the water temperature the

eggs are in. Water striders can live for many months.

The ability for one brood of striders to have young with wings and

the next without, allows them to adapt to changing environments. Long,

medium, short and non-existent wing forms are all necessary, depending

on the environment and season. Long wings allow them to fly to a

neighbouring water body when one gets too crowded.

However, long wings can get wet and weigh a water strider down. Short

wings may allow for short travel, but limit how far they can disperse.

Non-existent wings prevent them from being weighed down, but prevent

dispersal.Sudden increases in salt concentration in the water of gerrid

habitats can also trigger migration of water striders.

They will move to areas of lower salt concentration, resulting in the

mix of genes between brackish and freshwater species.

|

The sea skater or marine water strider, *Halobates

sericeu |

They also burrow into the mud when their habitat dries up, remaining

dormant until the water level comes back o normal.

As habitat, water stridesr prefer an environment abundant with

insects or zooplankton and containing rocks or plants for them to

deposit eggs on. It has been found that they prefer water bodies around

25 degrees Celsius with temperatures lower than 22 degrees Celsius being

considerd unfavourable.

This may be due to the fact that the development of their young are

temperature dependent. Some of the most prominent varieties of Gerridae

are found in Wales, the former USSR, Canada, USA. South Africa, South

America, Australia, China and Malaysia.

They control insect populations, especially mosquitoes, and are

therefore helpful to humans. They don't bite humans and are not harmful

to them.

- IT |