Should we stop time?

We spend it, waste it

and then wish that we had more of it. In Brazil, there's a tribe that

doesn't believe in it - and many physicists feel the same way. So why is

time such a contentious concept - and could we put an end to it all

together?

by Michael Brookes

When it comes to time, your brain is making a fool of you.

Everyone has their own story of when time ground to a halt, for

instance.

Mine was when a car knocked me from my bicycle. I was 12 years old. I

remember flying through the air after the impact, and thinking how

strange it was to be able to think so clearly while airborne. But that's

almost certainly a false memory. In dramatic moments, time doesn't

really slow to the point where you can pay attention to details.

We know this because David Eagleman, an associate professor of

neuroscience, and Chess Stetson, one of his postgraduates, once

persuaded a group of people to throw themselves off a tower from a

height of 46m (151ft).

The tower was at the Zero Gravity amusement park in Dallas, Texas,

but the experience was clearly far from amusing.

There's a clue in the title of the research paper they published

afterwards: Does Time Really Slow Down During a Frightening Event?

Eagleman said it was the scariest thing he had ever done.

|

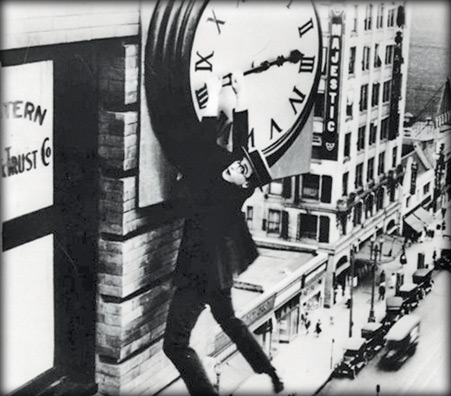

Time on his hands: silent comedian Harold Lloyd grasps the

hands of a skyscraper’s clock in his film ‘Safety Last’ |

During their free-fall, the volunteers read out any numbers they

could see on a "perceptual chronometer" attached to their wrists. This

device was a square array of 64 red LED lights.

A display of the number in LED lights - red on black - was alternated

with the illumination pattern inverted: the same number was then

displayed black on red. The human eye can see the difference if the

alternation happens slowly enough, but at a sharp threshold in speed the

two become superimposed and the display looks as if all the lights are

on.

If time really does slow down and perception is heightened when you

are in a frightening, life-threatening situation, the researchers

reasoned, the volunteers should be able to see the numbers. First, they

tested the threshold speed at which the volunteers could see the

flickering number.

Then they gave them a test jump and asked them to estimate how long

the fall lasted. With a safety net installed 15m above the ground, the

fall took 2.49 seconds, but the participants all overestimated their

fall time by roughly one third. Time, it seems, really was slowing down

inside their heads.

Then the researchers made them jump again, this time wearing

perceptual chronometers set to one-third above their threshold flicker

speed.

Number

If time really was slowing down, they should be able to see a number

as they fell. Eagleman and Stetson ended up with only 19 data points,

because one volunteer kept her eyes closed all the way down. But it made

no difference: none of the fallers saw a number.

There is no evidence to support the idea that time ever runs in slow

motion.

The truth is, time doesn't actually run at all. The whole thing is an

illusion.

Ticking off: most of those at the cutting edge of physics don't

believe in the notion of time and think it should be banished altogether

(Alamy) At the cutting edge of physics, very few people still believe in

the notion of time. In 2008, the Foundational Questions Institute, a

kind of think-tank for physicists, held an essay competition on the

nature of time. Some of the world's leading researchers entered and laid

out their stalls for how we should view time. Carlo Rovelli, of the

University of Marseille, suggested that if we want to unite quantum

theory and relativity - the ultimate goal of theoretical physics - "we

must forget the notion of time altogether".

Fotini Markopoulou Kalamara, of Ontario's Perimeter Institute for

Theoretical Physics wrote that we would have to ditch the notion that

physical space is real if we want to save time (she believes that the

trade is worth it). The winner of the competition, Julian Barbour, of

Oxford, took no prisoners. "Unlike the emperor dressed in nothing, time

is nothing dressed in clothes," he said. "Time," he concluded, "should

be banished." We already know that the universe has no truck with time.

In his Principia Mathematica, Isaac Newton wrote that, "Absolute, true,

and mathematical time, of itself, and from its own nature, flows equably

without relation to anything external... All motions may be accelerated

and retarded, but the flowing of absolute time is not liable to any

change."

But Newton was wrong, as Einstein proved in his special theory of

relativity. We now know - and have shown in experiments - that the

passage of time is different for people who are moving in different ways

through the universe.

That means it is possible for two people to move relative to each

other in such a way that they can both see two events but cannot agree

on which one of them happened first. Another casualty is the concept of

a universal "now": one person's present moment is in another person's

past, depending on how they are moving relative to one another.

Quantum physics, our most successfully proven scientific theory, does

not consider time as something worth even including as a measurable

phenomenon.

We already had hints - such as the fact that photons, the quantum

particles of light, don't experience time. But last year, Viennese

researchers showed that quantum particles can simultaneously exist at

two separate moments at once.

Imagine Einstein and Newton are bound only by the laws of quantum

theory.

The theory says that it is possible for Einstein to walk into a room

and see a message that Newton has left for him. He erases the message,

then writes a reply.

As Einstein finishes, Newton comes into the room to write the

original message. It's what's known as a superposition: two seemingly

separate possibilities both occurring at once.

In this case, Einstein was in the room before Newton and Newton was

in the room before Einstein. It is, as sometimes happens with

relativity, impossible to say who came into the room first. Why? Almost

certainly because time isn't a fundamental component of the universe.

There is no way to make this palatable; our common sense tells you that

it can't be true. However, common sense is not a useful guide to

reality. And if the physicists have taken away our time, at least they

are helping to explain why we think it's still there.

In 1967, two renowned physicists, Bryce DeWitt and John Wheeler,

found a way to bring quantum theory and relativity together to create an

ultimate theory of reality. You won't be surprised to hear that the

scheme involved ditching the notion of time.

However, in October last year, a group of Italian researchers made an

intriguing breakthrough. They showed that those inside DeWitt and

Wheeler's universe would still sense time passing.

They created a physical system involving two photons and demonstrated

that the photons' properties were static when viewed from outside the

system, but changed when viewed from within. The explanation comes from

the "observer effect", where quantum properties of particles are

affected by being measured.

Circling back to our everyday lives, it's clear that Barbour's idea

of banishing time could never work.

Description

We can't even bring ourselves to redefine time in modern terms. While

we have decimalised almost every description of the physical world, we

still work with primitive measures of time.

The Babylonians knew of seven planets, which is why we have seven

days in a week.

There are 12 hours in each day and each night because they gave one

hour to each sign of the zodiac.

We have 60 minutes in an hour because they thought 60 an auspicious

number. There are other ways of doing it. Thousands of years ago, China

ran on decimal time; the Chinese foolishly gave it up when Jesuit

astronomers brought them the European system. Decimal time made a brief

reappearance after the 1789 French revolution. Pierre-Simon Laplace, the

mathematician, even had a watch that gave decimal time, and he wrote his

celebrated Treatise on Celestial Mechanics using decimal time units.

In the end, though, the Babylonians prevailed - largely because of

economics.

Nations that built their wealth on an ability to navigate the oceans

for trade were loath to give up their sextants, theodolites, charts and

tables - all configured for the Babylonian system. These days that

obstacle has gone; GPS uses atomic time, which is based on the frequency

of radiation emitted by caesium -133 atoms. However, we use that atomic

standard to define the second, not to change it.

The Greenwich Meridian which sits at the centre of our system of time

zones (Alamy) Modern life, it seems, won't allow us to mess with time:

it's just too precious to us. It is perhaps telling that only the most

untouched of remote tribes has the most scientifically accurate

relationship with time.

The Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau people of Brazil can talk in terms of one event

happening before or after another, but they have no abstract concept of

time as something separate, as a background in which things happen.

Their language has no word for time as a stand-alone idea. They have

no word for month or year.

It's impossible to imagine living like that - in our culture, notions

of the passage of time are sacrosanct. That is why we might see an

international incident over time next year. The crisis is coming

because, thanks to tidal forces from the sun and moon, the Earth's spin

is slowing down.

As a consequence, the days - defined as one full rotation of the

planet - are getting longer. We have been compensating for this since

the 1970s by adding a "leap second" every now and then, but there is a

rumbling against this.

Technology companies who have to insert the leap second into their

computers' software on an ad-hoc basis complain that it's a pain, and it

sometimes goes wrong and makes computer systems fall over.

The governments of most countries have agreed that this means we

should stop inserting leap seconds.

The UK's Science minister, David Willetts, thinks it would be foolish

to sever our cultural connection between the sun and our clocks just

because it gives computer programers an occasional headache.

Not that the effect of ditching the leap second is going to be

terribly noticeable for a good while yet: if we do stop inserting it, it

will take 600 years before the sun is at its highest point at 12.30,

rather than noon.

Nonetheless, Willetts is exercised enough about the issue to have

commissioned a public consultation to find out if we all agree with him

before he (or his successor) has to participate in an international vote

on the matter in 2015.

If the vote goes against the technology community's desire to abandon

the leap second, it's always possible that the companies will just

redefine time for themselves. There's no reason why they couldn't

implement a proprietary time-stamp on their devices and software; before

too long, some of us might be running our lives on Google Time.

Perhaps that will be the moment we accept that time really is the

ultimate delusion.

- The Independent

|