Anne Frank and the cult of the diary

From Samuel Pepys to Bridget Jones,

the private journal combines the mundane with the confessional. Lucy

Scholes reveals why the diary still fascinates readers.

It's a story so well-known it doesn't need much elaboration. On 6

July 1942, just a month after Anne Frank received the diary that's since

become so famous, she, her father Otto, her mother Edith, and her older

sister Margot went into hiding in a secret annex in Amsterdam. They were

joined by another Jewish family, Hermann (a colleague of Otto's) and

Auguste van Pels and their son Peter, along with Fritz Pfeffer, the van

Pels' dentist. The eight remained hidden away for two years and one

month until, in August 1944, they were discovered and dragged off to

concentration camps. Anne's diary was found by some of Otto's colleagues

who kept it safe in the family's absence. Anne died of typhus along with

her sister in the Bergen-Belsen camp in March 1945 - 70 years ago this

month - shortly before it was liberated by British and Canadian

soldiers. Otto was the only member of the family to survive the war.

"I hope I will be able to confide everything to you, as I have never

been able to confide in to anyone, and I hope you will be a great source

of comfort and support," Anne writes in her first entry on 12 June 1942,

perfectly encapsulating the motivations of the adolescent diarist.

Diaries stand as memorials to the mundanity of everyday routines, but

they also offer the comfort of the confessional, the blank pages

offering a sympathetic and non-judgemental ear into which secrets can be

whispered; in Anne Frank's case, fears for her life and that of her

friends and family intermingle with schoolgirl crushes and exasperation

with her parents. Just like any other teenage diary, Anne's began as a

personal account written for her eyes only, but all this changed in

March 1944 when she heard a radio broadcast from London in which the

exiled Dutch minister for education, art and science called for the

preservation of what he described as "ordinary documents" detailing the

experiences of his countrymen and women under Germany's occupation. Anne

went back over her earlier entries and began re-drafting them with the

end goal of publication, and a public audience, in mind.

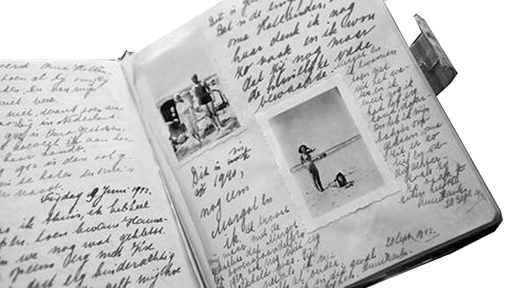

|

Just like any other teenage diary, Anne’s began as a

personal account written for her eyes only, but all this

changed in March 1944 (Credit: AP Photo) |

Although she didn't live to see her ambition realised, Otto pursued

his daughter's dream and the first edition of The Diary of a Young Girl

was published in 1947. Since then it's been translated into 67 languages

and has sold more than 30 million copies worldwide, ensuring Anne

Frank's name in the annals of history.

The critical and commercial consensus is that the book is a

remarkable work, both as a historical document and as an example of a

talented young writer. But it's in the coming together of these two -

the marriage between the personal and the public, the individual

experience and the universal - that the diary's particular potency lies.

Teenagers today read it with such interest, more than 70 years after it

was written because it's an account of the trials and tribulations of

growing up that still resonates.

Notes on a scandal

"What sort of diary should I like mine to be?" Virginia Woolf asks in

a journal entry written in 1919. "Something loose knit and yet not

slovenly, so elastic that it will embrace anything, solemn, slight or

beautiful that comes into my mind. I should like it to resemble some

deep old desk, or capacious hold-all, in which one flings a mass of odds

and ends without looking them through." The vast majority of diaries

conform to Woolf's hold-all metaphor, but those published must have the

coherence she aspires to. Many writers keep diaries, whether as a medium

through which to hone their craft, the result of a compulsion to write,

or simply the same ego-driven impulse that induces the rest of us to put

pen to paper. By comparison, our interest in reading these works is a

tad more complicated.

The tension between the public and the private is at work in all

published diaries. Diaries are by nature supposed to be secret: reading

them, regardless of how legitimately they've been presented and packaged

by a publishing house, is something of a violation. This, in part,

explains why they're so popular; that taste of transgression is

tantalising, especially when it comes to the more scandalous offerings.

From the Marquis de Sade to Anaïs Nin, notorious journals delight and

repel in equal measure.

Obviously there's the value of a diary as a historical document; what

we learn about Restoration London from the diary of Samuel Pepys, for

example - his eyewitness accounts of the Great Fire and the plague - has

been invaluable to those studying the period. Then there's the diarist

as voyeur, one whose journals provide the reader with a fly-on-the-wall

view of a world otherwise bared to them. From Dorothy Wordsworth (sister

of the famous poet, William) to Andy Warhol, and all the American

presidents and presidential advisors in between, these journal keepers

offer us something similar to the guilty pleasures afforded by the

magazines and websites that pander to our contemporary

celebrity-obsessed culture.

'Warts and all'

But there are also those diarists who seem to spin their own myth as

they write. Perhaps the prime example here is not an individual so much

as an entire collective: the Bloomsbury Group. "Were their lives really

so fascinating," the cultural critic Janet Malcolm asks, "or is it

simply because they wrote so well and so incessantly about themselves

and one another that we find them so?" Their great achievement, she

surmises, is that they "placed in posterity's hands the documents

necessary to engage posterity's feeble attention - the letters, memoirs,

and journals that reveal inner life and compel the sort of helpless

empathy that fiction compels."

This last assertion is particularly interesting - diaries captivate

their readers when they function in a similar way to novels, inspiring

sympathy in the reader. On the flipside, of course, is the attraction of

the fictional diary. It's a structure often used by children's fiction

and YA writers - from Jeff Kinney's Diary of a Wimpy Kid series and Meg

Cabot's The Princess Diaries, to Dodie Smith's I Capture the Castle and

the more recent The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky -

precisely because it's the quickest way of drawing readers into the

consciousness of the protagonist they're reading about.

Satirists love the diary form because of the same immediacy. George

and Weedon Grossmith's spoof The Diary of a Nobody that pillories its

fictional author, the snobbish middle-class Mr Pooter, was not only an

instant hit on its initial publication (in serial form between 1888 and

1889 in Punch magazine), it's also never been out of print in the UK

since. Written in the same humorous vein is E M Delafield's caustically

funny take-down of 1930s English middle-class domesticity The Diary of a

Provincial Lady.

More recently, Sue Townsend's comic The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole,

Aged 13 3/4 was a bestseller in the 1980s, spawning seven sequels,

seeing its protagonist through to "the Prostate Years" in 2009. And, of

course, the '90s had its own diary-keeping heroine: Bridget Jones, Helen

Fielding's bumbling, white-wine swilling, cigarette smoking singleton

searching for her Mr Darcy. We enjoy a fictional diary, it seems, for

much the same reason we enjoy a real one: the allure is the promise of a

portrait devoid of artifice (it's the warts-and-all element from which

the comedy is so easily extracted). But this isn't simply the assumption

that reading someone's diary allows you a unique insight into their

mind.

This lack of pretence extends to the very structure of the narrative.

One of the attractions of a diary is the reader's knowledge that the

story is constantly in the process of being constructed - even in

fictional versions, the success of the book is dependent upon this being

believable. Wartime diaries, for example, are hugely popular - from Vera

Britten to Joan Wyndham, and the offerings of every unknown soldier or

nurse in between - this is because the medium effortlessly fits the

message, capturing the fragmented and ephemeral day-to-day existence of

not knowing what tomorrow will bring.

-BBC |