The critical 1%

CBK's final efforts at peace:

by Dr. Ram Manikkalingam

On August 12, 2005, the Foreign Minister of Sri Lanka, Lakshman

Kadirgamar, was killed by a sniper's bullet. The sniper had been

watching Kadirgamar for weeks. He knew he would have only a second or

two to get his shot off and that he would only get one chance.

|

|

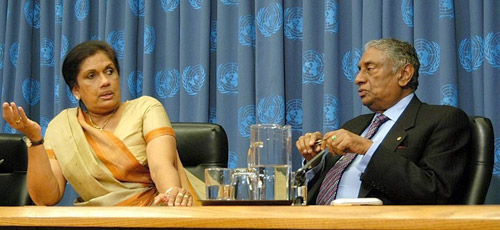

Former President Chandrika

Bandaranaike Kumaratunga with former Foreign Minister Lakshman

Kadirgamar at a UN Session. File Photo: ANCL Library |

After President Kumaratunga, Lakshman Kadirgamar was the most

protected person in the country. He travelled in an armour-plated

vehicle. He had dozens of commandos protect him. His convoy included

motorcycle outriders, point vehicles and back-up cars. His visitors

faced a security cordon, almost as stringent as that of the President.

The sniper pulled the trigger and struck Minister Kadirgamar down.

It was a sombre day when Lakshman Kadirgamar was cremated. Foreign

Ministers from neighbouring countries - India, Pakistan, Nepal and

Bangladesh and the entire foreign corps were present. President

Kumaratunga was devastated. There is a photograph of her at the funeral

wearing dark glasses.

Lakshman Kadirgamar's assassination was a doubly devastating blow. It

was the death of her foreign minister, her close colleague and friend of

11 years. And it was also the death of peace-something she had worked

hard for and believed in during her entire tenure.

Death of peace

In retrospect, Kadirgamar's killing changed everything for President

Kumaratunga's efforts and for the prospects of a peaceful end to the

conflict in Sri Lanka. Eventually, it led to another period of war in

the country. For, the assassination of Lakshman Kadirgamar was not an

isolated act; it came as a calculated decision made by the LTTE - an

organization that had come to deeply believe in violence.

As a leftist critical of Tamil extremism, I chose differently and was

willing to work for President Kumaratunga, who wanted to build a lasting

peace through political negotiations. The immediate context of our

negotiations was the ceasefire that had been established by Prime

Minister Wickremesinghe and signed in 2002. The ceasefire was being

mediated by the Norwegian Government.

The ceasefire had initially been fairly effective in holding down the

violence between the Tigers and government forces. It helped open access

to areas of the North and East that had been closed down for years. But

the ceasefire was not leading to any genuine dialogue about a lasting

peace.

During the 1990s, both the government and The Tigers had pretended

that violence was achieving results. But the illusions of victory

created by counting bombs and bodies could not mask the reality that

neither the Tigers nor the government was winning. The fighting had

reached a stalemate, to which the nominal ceasefire gave formal

recognition. Many analysts had come to the conclusion that further

military victories on the part of the State would require the use of

overwhelming force. But the problem with overwhelming force is that it

can succeed militarily and still fail politically. Nobody was sure how

to cut this Gordian knot.

With President Kumaratunga's leadership, we decided to try something

different. We rejected the easy solutions of hardliners: take on the

Tigers with guns, bombs and soldiers; ignore the pain and suffering

caused by war; disregard death and destruction; detain thousands of

Tamil civilians; restrict the flow of food and medicine; and deny that

Tamils were politically disenfranchised.

The UNP Government of the 80s under J.R. Jayewardene had taken

exactly this hard-line approach. They enacted draconian laws with the

power to detain people indefinitely. They shut the door on participation

by the country's largest Tamil party, TULF (Tamil United Liberation

Front), by making endorsement of secession a crime. They militarised the

Tamil areas, and they 'disappeared' thousands of Tamils. The result was

not encouraging. The tenacity of the Tiger-led rebellion only increased.

With the failure of the hard approach, there was always the hope that

a soft approach would transform a nasty enemy into a trusted negotiating

partner. This was the approach taken by the Wickremesinghe Government

with the ceasefire. While it may have been well intentioned, it was also

clearly not working.

So, President Kumaratunga began to develop an approach that was hard

on hard issues and soft on soft issues. We stopped treating Tamil

civilians like Tiger guerrillas. We discouraged the military from

committing excesses on the battlefield.

We were going to do everything we could to make life easier for Tamil

civilians and make war harder for Tiger fighters. And we developed

wide-ranging proposals for a political arrangement that would address

the concerns of the Tamil people and help them to live with dignity.

At the same time, President Kumaratunga was tough on the Tigers. When

the Tigers sought to land arms by sea in the midst of the ceasefire, she

ordered their ship sunk by the Navy. When the Tigers recruited children

she raised it with the Norwegian facilitators, demanding that this be

stopped. When the Tigers killed agents of the military in the North, she

ordered a crackdown on the Tigers and restricted their movement, even

though - or especially because - we were in the midst of a ceasefire.

International pressure

The Tigers, however, needed 'men' with guns. Most Tamils had fled the

war. Very few adults were left behind to conscript. The Tigers had

reached the limit of their recruitment. So they turned to the children.

In the face of international pressure, the Tigers feigned cooperation

with UNICEF, sending injured children, or those who could not fight, to

these rehabilitation camps, still using the healthy children as

soldiers.

Despite the clarity of our framework for engagement, everything

became a subject for intensive debate. For example, should we criticize

Nordic ceasefire monitors when they seemed to allow Tiger abuses? Should

we threaten to bring in other monitors? At what point should the

government respond and at what level? If the Tigers were to assassinate

State military intelligence operatives in Tiger-controlled areas, should

the government respond in kind in areas under government control?

On the face of it, the response might seem obvious - halt all Tigers

from moving into areas under government control. But if part of the

strategy was to get the Tigers more 'comfortable' with doing politics,

then shutting off their political wing from doing political work,

however rudimentary, undermined this long-term political goal. And

without a political unit arguing the case for peace, it was hard to

imagine anyone else in the Tigers ever doing so. Ultimately, the

Kumaratunga Government felt the best strategy was to covertly move

against Tiger intelligence operatives, holding up the Tiger movements

between areas they controlled, while continuing to permit Tiger

political cadres to engage in non-military activity.

President Kumaratunga knew that the ceasefire on its own was

insufficient to maintain peace. In the absence of political talks, we

needed something more. That is when we hit upon a soft issue we felt

would really make a difference, a reconstruction-oriented peace dividend

for both civilians in the North and the Tigers.

Importantly, from the point of view of avoiding hostilities, this

work kept military cadres within the Tigers busy with reconstruction

instead of waging war. Liaising with a senior official of the Health

Ministry or the Road Development Authority required the Tigers to send a

relatively senior counterpart -someone who was commanding at least a

couple of hundred men.

When engaged in development efforts, this Tiger commander was no

longer training and preparing men for war and, simultaneously, he was

getting a taste for peace. Indeed, the pride these commanders

demonstrated in completing reconstruction projects was palpable.

Reconstruction work

These reconstruction efforts were piecemeal. They served their

immediate purpose of delaying any resumption of the war. But they were

still not widespread enough to set the stage for making peace.

That was exactly the challenge we grappled with on a daily basis. We

had a ceasefire. We had a team to monitor the ceasefire. We had a

facilitator. We even had a group of friendly nations - the European

Union, Norway, Japan and the United States - to assist in the process.

But we still did not have political talks almost two years into the

ceasefire.

The lack of any concrete movement toward a more sustainable peace was

becoming a problem.

Even in the darkest moments of the ceasefire and the peace talks,

there was always that 1% chance for peace. It was something to work

with. That was my job, to not give up hope or succumb to pessimism,

however 'objectively' justified.

It may sound strange, but from a political or intellectual

perspective, going to war is not difficult. It requires denying the

others' humanity, buttressing support amongst your own, taxing the

people, conscripting soldiers and buying bigger and better guns. The

most challenging part is being willing to accept (or alternately deny)

the sorrow of war.

Even if in those months and years when it was beginning to feel like

the prospects for peace were close to 1%, I saw it as my job to hang

onto that 1% and transform it into 5, 10 and 50%. It is not in the job

description of a peace-maker to despair, nor to give up. And President

Kumaratunga did not expect us to.

But when it came to the Tigers, the very idea of getting beyond 1%

was beset with unavoidable stumbling blocks. Here we have a group that

resists politics and opts for armed conflict almost by its very nature.

Here is a political situation in Sri Lanka where, in a complex

historical development that took decades to mature, the ground was

almost perfectly prepared for war.

We wanted to get into direct talks with the Tigers. But instead of

moving straight to actual talks, the talks immediately got mired down in

the question of what the agenda for the talks would be.

The government wanted to talk about a permanent settlement. What

would a political solution look like? How much autonomy would the Tamil

regions have? What political power would the Tamil majority provincial

council have? How much money could they raise through taxes? Would they

have their own police force or would the police force be appointed from

Colombo? Would a Tamil council be permitted to raise funds overseas?

What would happen if such a council raised its own militia? Lurking

behind these questions was our ultimate worry. Would all of these

developments eventually lead to separation? We wanted some assurances

that the country would not be divided before we discussed our next

steps.

But the Tigers took the opposite tack. They wanted to talk about an

interim solution.

They wanted to know what powers an interim administration would have

without clarifying whether this interim entity would be within or

without Sri Lanka. For them the goal of a political settlement at the

end of the road - even if formalised in an agreement - was too vague a

commitment on which to abandon their fight of over three decades. They

wanted to know what it was that they would get here and now.

Obtaining interim powers for an interim settlement, allowed them to

say to their supporters that this was only a qualified solution that

depended on how the Sri Lankan Government would behave. If the Sri

Lankan Government failed to deliver, they always had the option of

reverting to war. The fears and distrust on both sides were clear. The

Norwegian Government tried to overcome this by drafting an agenda for

talks that both sides could accept.

The search for the agenda began. First, there were a series of drafts

that were meant to toe the line between an interim and a permanent

settlement. The Tiger leader and the Sri Lankan President were

constantly scratching out and adding phrases. When this failed, we tried

an agenda that discussed the permanent solution first, followed by the

interim one. The Tigers turned this round - discuss the interim solution

first, followed by the permanent one.

We said no. What about interim in the context of the permanent? They

said what about permanent in the context of the interim? And so it went,

with the poor Norwegians reaching the limits of their language skills,

and us our political ones. We could not even agree about what possible

talks might look like, let alone the possibility of a future peace.

Proxy battle

We were second-guessing and reworking drafts in our search for the

perfect wording, when no amount of wordsmithing could solve the

political problem of trust. The political pressure of the process and

the polarization caused by the ethnic conflict had become reduced to a

proxy battle over the wording of the agenda.

We could stop fighting, but we could not start talking. We needed

radical input from outside to shake things up and bring us to the table.

Tragically, this input came from no human actor, but from nature, in

the form of the tsunami of December 2004. Like the Hindu god of

destruction, Lord Siva, who dances as the world ends, the tsunami - one

of the worst natural disasters in recorded history - wreaked havoc on

all our communities in equal measure. Suddenly it mattered less what we

- Tamils, Sinhalese, Muslims, and Burghers - were doing to each other,

and more what something else, the tsunami, had done to all of us. In the

space of a few minutes, we lost the same number of lives that the war

had taken from us in three decades.

Post tsunami overture

Sinhala farmers, living in the hinterland of Sri Lanka, loaded

lorries and tractor trailers with foodstuffs for Tamils on the coast

affected by the tsunami.

They were the first to provide aid and succour to those affected, not

the international volunteers who showed up later. Military units known

for their harsh measures- not just against the Tigers, but also against

the Tamil people - risked their lives to assist Tamil victims.

This enabled us to begin talks that led to an agreement to jointly

engage in reconstruction. We were at pains to point out that this

mechanism was not political, but only humanitarian. By calling it

humanitarian, the Tigers and government were able to create the

political space to talk. In the aftermath of such destruction - a

million displaced and thirty thousand dead - it was hard for even the

hardest of hardliners to oppose working together on rebuilding

communities.

We called this a humanitarian issue. But we knew that if it worked,

it could create the climate for something more. The talks around the

tsunami created hope that we could build on the 1% that we were moving

from the realm of dreams about a possible peace into a more concrete

reality.

The agreement to set up a joint body between the Tigers and the

Government to do reconstruction was eventually signed at the end of June

2005, six months after the tsunami. Unfortunately, this agreement came

too late. The political sands were already beginning to shift beneath

our feet. As the talks dragged on, the agreement looked less and less

solid.

The Muslim representatives wanted to be co-signatories. But the

Tigers rejected this. Finally, the build-up of political opposition made

it easy for the Supreme Court (traditionally unsympathetic to minority

concerns) to block the agreement in a landmark decision for the future

of Sri Lanka's war.

When this happened, I knew it meant the end of the politics of talks.

But I hoped this would not be a return to the politics of war. I was

proved to be wrong. The 1% was not growing in the cooperation that came

immediately after the tsunami; it was sinking toward zero. The Tigers

communicated their displeasure about the Supreme Court decision in their

usual manner. They sent a sniper. And Lakshman Kadirgamar was killed.

At midnight, shortly after the killing, I received a call from the

chief of the President's security. I was told to get ready. They were

sending a limousine to pick me up. The President wanted to meet with her

advisers to discuss how to respond to the killing. As the car sped

through the deserted streets of Colombo, I had no idea the decisions we

were to take that night would contribute to the inexorable pull of war

and lead to the bloody denouement on a sandy strip of beach in Northern

Sri Lanka four years later.

I was confounded by the brutality of the Tigers.

Their resort to violence to correct a situation they didn't like was

hardly surprising. But that they did this in the midst of a ceasefire

under the gaze of the international community, and so soon after the

tsunami, seemed extreme even for them. The Tigers were now demonstrating

complete disregard for what the world would think. Where was our

leverage, other than military, if the Tigers cared naught for what the

world thought? The President wanted to respond to this Tiger action in a

decisive manner. But she did not want to break off the ceasefire and

return to an all-out war.

Making peace

After a brief but intense discussion, she made the decision to

declare a state of emergency. This gave the Police and the Armed Forces

the powers of search and seizure without judicial authorisation. It also

permitted restrictions on assembly, movement and in some cases, even

speech. These measures have draconian result on the functioning of civil

society when used in a widespread and systematic manner. And they can

have negative repercussions, as we were well aware from previous

experiences in Sri Lanka. Still, a draconian law seemed a lesser evil

than a declaration of war.

The President also wanted to send a clear message to the Tigers

internationally. The killing of the Foreign Minister would have severe

repercussions for them.

One of these was the ban on the Tigers in Europe, which had a large

Tamil diaspora. The Tigers were already banned in India, the United

Kingdom and the United States. Going further meant asking the European

Union to include the Tigers on their list of terrorist organizations,

which until then had refrained from doing.

In the space of one day, we had moved from engaging the Tigers to

seek a decent peace into the opposite direction entirely. To our

thinking at the time, they had not just killed the Foreign Minister, but

also the very idea of peace in Sri Lanka.

My hope in the 1% chance for peace was gone. We had reached 0%. This

is a far more radical shift than from 25% to 1%. At 0%, peace is no

longer possible.

The balance had shifted from how to pursue peace to how to wage war

more effectively. I had given up hope of re-engaging the Tigers. It was

an uncomfortable place to be.

Within four months (December 2005), President Kumaratunga was out of

office and, as her advisor, I was out of a job - no longer involved in

peace negotiations. A new government was in place.

Our failure to keep the chance for peace alive moved rapidly into a

period of outright war. By August 2006 the die was cast - both sides had

decided to fight first and talk later. This crisis was now going to be

resolved by force of arms. War was not only inevitable, but also

required before any fresh political process could emerge. By mid May

2009, they had both gotten their wish, though not as the Tigers had

expected and with results and costs that are still a matter of

controversy today. |