The return of the exile

Activist, journalist and blogger,

Sunanda Deshapriya talks to Dilrukshi Handunnetti on journalism in

exile, digital platforms of advocacy, media reforms and the crucial need

for public service media

|

|

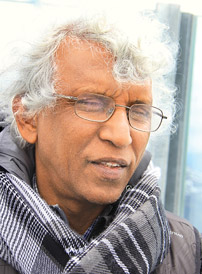

Sunanda Deshapriya, speaks

at a protest against the assaults on journalists during a

demonstration in Colombo July 2, 2008. REUTERS |

Driven into self exile in January 2009, in the immediate aftermath of

the brutal slaying of The Sunday Leader editor Lasantha Wickrematunge,

it is his first visit to the country of origin in six long years. At the

time of departure, Sunanda Deshapriya was labelled a 'traitor' along

with the likes of Wickremetunge, for voicing democratic dissent. "We

felt there was no option but to leave," he says.

Much has changed and much hasn't changed in Sri Lanka in six years,

claims Deshapriya, who feels a sense of disconnect, upon return.

Somewhere somehow, the years of separation had created a gulf that makes

him feel less integrated into his own society. "That feeling is a shared

one," he muses.

Being away, on the other hand, has given him the opportunity to

critically look at Sri Lanka and review its developments. His first

acknowledgment is of the broadening of democratic space post January 8

and some positive changes in the media landscape, which he considers a

'point of departure.'

"But I see partisan trends continue. What is gone is the suppression

and oppression. Clearly, nobody threatens journalists or have them

killed and assaulted.

That's a huge change for a country that had lived through serious

intimidation and violence against journalists. The next step is the

systemic changes that come through policies, mechanisms and practices."

Deshapriya also finds that economic control over the media, a

continued practice, 'policed by respective owners.' "This kind of

ownership control with heavy political leanings has got crystallized in

the past few years," he notes.

What Deshapriya regrets is the media's own inability to retain some

of the January 8 momentum by influencing the industry. "Change must come

from within ourselves. With the change in the national leadership, some

democratic space was created. It allowed the media industry an

opportunity to leapfrog. That's still missing."

Public service media

A strong believer of public service media, Deshapriya claims best

results can be achieved - despite existing drawbacks - through the

reformation of the State-owned media institutions into public service

models. A strong believer of public service media, Deshapriya claims best

results can be achieved - despite existing drawbacks - through the

reformation of the State-owned media institutions into public service

models.

"That's where the ownership control does not exist unlike in the

privately-owned media. There may be strong management control but that's

different to economic power being applied over media houses. It is only

the JVP that does not have the backing of a large media house, all

others do."

Learning from successful global models, Deshpariya insists that

quality journalism can flourish in State-owned media. "It must happen,

using the space created in January. The best course of action is to

either convert the existing State-owned media or the creation of

dedicated public service media outlets, modelled on existing

institutions elsewhere. From the servile to a service model," he quips.

What he does regret is the changing of gear with the announcement of

a crucial August 17 general election that has pushed the discussion on

media reforms to the political backburner. In that lost opportunity, he

also finds media behaviour changing, reflecting the political urgency

that is natural during a crucial election, regretfully sliding back to

old repulsive media culture. "There are hardly any progressively steps

taken to push the envelope, using the newly discovered space."

Dehsapriya says that "journalists must redefine their own role,

within the restrictions of the media landscape, both political and

economic.

One has to be impartial in crisis. During peace time, it is easy to

remain calm. This is the acid test for the Sri Lankan media: to

demonstrate their ability to withstand pressures and be professional,

converting the January 8 success to full-blown opportunity for positive

change."

He recalls seeds of public service broadcasting being sewn by the

late Tilak Jayaratne through the inspirational Uva Community Radio.

There were other models like the Ruhuna and Rajarata broadcasters,

which had local leadership and local flavour. "While the tags may

differ, we need models like the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC)

and National Public Radio(NPR).

Public-owned and public- led should be the model. That's the future."

In the scramble to enter parliament in August and secure majorities,

Deshapriya says that nobody makes a public commitment to "introduce a

public service media."

The next government, he insists, should ensure a strong commitment to

fostering public service media, make them sustainable and guarantee

their independence.

The conversion of the existing to a new model admittedly is

debilitated by the State-owned media's lack of credibility, after years

of being abusively used as 'disgraceful political tools.'

This trust deficit, he says, is being overcome in small ways but

needs to be strengthened. "State-owned media should reflect diversity

and give voice to public concerns, beyond the mere political.

The problem is, people do not believe that that State- owned media

are a platform for public discussion and engagement."

Beyond the models, the State must also investment in good journalism.

"The political conditions are much better. There is great scope, only if

they want to try. Political cohabitation has made it difficult to

practice ugly party politics, all of which should help us reach the next

level: a committed, professional, public-spirited media."

The public revulsion also stems from the use of State media not

merely for political propaganda but largely as platforms of hate speech

and serious polarization. There had been instances when they contributed

to the incitement of violence against activists and dissident voices.

Deshapriya strongly believes that as much as it is difficult to

control information, so is opinion. With the advent of social media,

people freely express themselves online, their rage and outrage. Deshapriya strongly believes that as much as it is difficult to

control information, so is opinion. With the advent of social media,

people freely express themselves online, their rage and outrage.

"What is important to bear in mind is not the inability to control

expression, even when it is hate speech. What is alarming is the lack of

outcry against such hate speech. In other places, when hate speech ends

as tweets, there are thousands of tweets opposing that. That social

engagement is missing in Sri Lanka, though it happens in pockets. That's

not enough.

Opinion makers must immediately engage and express dissent. That

contributes to media diversity and continued dialogue."

Recalling a recent incident, he said a key campaigner for the former

president, Wimal Weerawansa, was spewing out venom in a publicly

broadcast speech. "He said, he did not advocate attacking those who

opposed Mahinda Rajapaksa but only wanted the public to throw hot water

on those who criticized him. It's outrageous. His comment is alarming

but what is more alarming is the lack of public response to that."

He recalls: "As a child, growing up in a coastal village in the

South, I used to hear a lot of hate speech. That had changed

drastically. Now hate speech is practiced by the literate. It has lost

its value as a social practice but become a campaign tool and

mainstreamed by politicians."

His departure from the island also had its links to being a target of

continuous hate speech and branding him as a 'terrorist.' Sunanda

Deshapriya admits that the level of hate speech in Sri Lanka a few years

ago, not only drove people into self exile but brought physical harm to

people.

Despite all that, Deshapriya remained engaged from where he made a

new home, in Geneva. "It is tragic that activists were compelled to

leave. To me, it is also tragic to find them abandoning their engagement

with their country of origin. Even when driven out, we could mainstream

ideas and help broaden democratic space."

Vicious cycle

"Once exiled, it's as if you end up in some kind of cold storage.

There is freedom, a new place, new languages to learn, challenges of a

different kind and material comfort.

Yet, there is something missing. Exiled people often wonder why they

need to be engaged with a native place that drove them out."

Six years later, Deshapriya is able to clinically analyze the

situation of the exiled Sri Lankan media. Many have their own issues to

deal with, families, a new culture and a society, new jobs and a

complete overhaul. These adjustments take time and support.

Deshapriya feels it is a matter of choice for those who have left.

"Personally, I still feel like an outsider. It is difficult to come back

in six years and pick up the threads of my scattered life. I don't feel

I belong and it is difficult to explain sometimes.

"I am growing old and there is less worry for me. But for young

people, it is doubly difficult. They have to consider uprooting their

families, come back to old jobs or look for new jobs.

They have to reconsider their safety issues and worry about the

possibility of security risks, if things change suddenly. They need more

social security in order to return, not just a conducive backdrop. Look

at those who returned from Nepal. It is difficult for them to find their

own place in Sri Lankan society again."

Dealing with trauma

Deshapriya is of the view that journalists often discount their own

trauma, having lived covered a decades-long conflict and lived through

it. "In Sri Lanka, we hardly acknowledge this.

As a society, we need to heal. This is also the reason who we fail to

tolerate dissent in a civilized manner and call for blood.

We are maimed and bleeding and we need to heal. If the cacophony of

noises is a result of a society in crisis and suffering from trauma, so

is the deafening silence, which is paralyzing."

Healing is a process, and one in which both family and friends have

huge roles to play. After years, families have become different,

children have gown and their attitudes have altered. Families have

evolved, in the absence of other family members, he says.

"There is a need for tolerance and offering space. To step back and

given that space to acclimatize and find our feet. It is also possible

to feel rejected by families and friends. When trauma is borne in

separation, this can happen" he adds.

"I feel I have a right to return but there is that loss of

connectivity. I carry within me, this hollow feeling, the sense of an

outcast, an alien. I felt the same way when I went to jail in 1971.

Of course in the prime of my youth, I felt I was a hero. I find a

parallel, 40 years later. Those who left, feel that we made a sacrifice

by giving up our right to live here, by raising our voices until being

driven out. But I feel that the greatest sacrifice was made by those who

stayed and continued to work within the restricted space."

Considering the decision to return a personal one, Deshapriya says

that what should not be an option is making a contribution to enhance

democratic space in one's home country."

One can remain engaged from their new found homes. For me, leaving

was a mistake, even though the stakes were truly high at that time."

There are lessons learnt from being an exiled journalist. In

hindsight, he feels there should be scholarships or some other learning

opportunity offered for a limited period, offered on the basis of

return.

In sending people out, countries that are geographically and

culturally close should be the first option.

"Sinhala journalists have never left this country en masse like this

before. Sinhalese have been migrating since 1940s but that's actual

migration, not exile.

The Tamil community has been migrating but this is a first for

Sinhalese to go as asylum seekers."

People of course are free to live anywhere. In the migration of

activists, the situation in Myanmar offers some examples, he notes. The

exiled journalists have operated from different places and had never

left their engagement. Post 2012, they have begun to return and are

taking their place in Burmese society, Dehsapriya notes.

'That engagement is missing here. We need to demonstrate our desire

to contribute to the democratization of our country of birth. Instead,

we appear to have cut our umbilical cord, firmly." |