Broken lives and social justice

New role for museums as Liverpool chooses focus on

human rights and be upfront about it:

by A.D. Mckenzie

|

|

Dr David Fleming, director

of National Museums Liverpool, which includes the city’s

International Slavery Museum. Credit: National Museums Liverpool

|

An exhibition on modern-day slavery at the International Slavery

Museum in Liverpool, is just one example of a museum choosing to focus

on human rights, and being 'upfront' about it.

"Social justice just doesn't happen by itself; it's about activism

and people willing to take risks," says Dr David Fleming, director of

National Museums Liverpool, which includes the city's International

Slavery Museum (ISM).

The institution looks at aspects of both historical and contemporary

slavery, while being an 'international hub for resources on human rights

issues'.

It is a member of the Liverpool-based Social Justice Alliance for

Museums (SJAM), formed in 2013 and now comprising more than 80 museums

worldwide, and it coordinated the founding of the Federation of

International Human Rights Museums (FIHRM) in 2010.

The aim of FIHRM is to encourage museums which 'engage with sensitive

and controversial human rights themes' to work together and share 'new

thinking and initiatives in a supportive environment'. Both

organisations reflect the way that museums are changing, said Fleming.

"Museums are not dispassionate agents," he says, adding, "They have a

role in safeguarding memory. We have to look at the role of museums and

see how they can transform lives."

The International Slavery Museum's current exhibition, titled 'Broken

Lives' and running until April 2016, focuses on the victims of global

modern-day slavery - half of whom are said to be in India, and most of

whom are Dalits, or people formerly known as 'untouchables'.

The display "provides a window into the experiences of Dalits and

others who are being exploited and abused through modern slavery in

India", say the curators.

"Dalits still experience marginalisation and prejudice, live in

extreme poverty and are vulnerable to human trafficking and bonded

labour," they add.

|

|

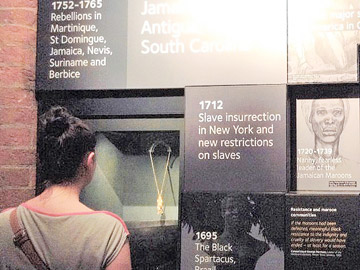

A visitor looking at a

panel at the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool, England.

Credit: A.D. McKenzie/IPS |

Presented in partnership with the Dalit Freedom Network, the

exhibition uses photographs, film, personal testimony and other means to

show 'stories of hardship' that include sexual servitude and child

bondage. It also profiles the activists working to mend 'broken lives'.

"Museums (in Liverpool, Nantes, Guadeloupe and Bordeaux ) hope that

they can play a role in global citizenship, educating the public and

encouraging visitors to leave with a different mind-set - about respect

for human rights, social justice, diversity, equality, and

sustainability"

Legacy of racism

The display occupies a temporary exposition space at the museum,

which has a permanent section devoted to the atrocities of the

trans-Atlantic slave trade and the legacy of racism.

Along with the Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery in the French

city of Nantes and the recently opened Mémorial ACTe in Guadeloupe, the

Liverpool museum is one of too few national institutions focused on

raising awareness about slavery, observers say.

But it has provided a 'vital source of inspiration' to permanent

exhibitions on the slave trade in places such as Bordeaux, southwest

France, according to the city's Mayor Alain Juppé. Here, the Musée

d'Aquitaine hosts a comprehensive division called 'Bordeaux,

Trans-Atlantic Trading and Slavery' - with detailed, unequivocal

information.

These museums hope they can play a role in global citizenship,

educating the public and encouraging visitors to leave with a different

mind-set - about respect for human rights, social justice, diversity,

equality, and sustainability.

"We try to overtly encourage the public to get involved in the fight

for human rights," Fleming says, adding, "We've often said at the

Slavery Museum that we want people to go away fired up with the desire

to fight racism. "You can't dictate to people what they're going to

think or how they're going to respond and react," he continues,

claiming,"But you can create an atmosphere, and the atmosphere at the

Slavery Museum is clearly anti-racist. We hope people will leave

thinking: I didn't know all those terrible things had happened and I'm

leaving converted."

Despite Liverpool's undeniable history as a major slaving port in the

18th century, not everyone will be affected in the same way, however.

There have been swastikas painted on the walls of the museum in the

past, as bigots reject the institution's aims.

Mobilising Memory

|

|

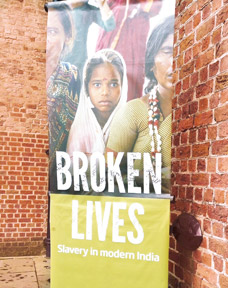

A poster sign for the

‘Broken Lives’ exhibition under way at the International Slavery

Museum in Liverpool. Credit: A.D. McKenzie/IPS |

"Some people come full of knowledge and full of attitude already, and

I don't imagine that we affect these people. But we're looking for

people in the middle, who might not have thought about this," says

Fleming.

He describes a visit to the museum by a group of English

schoolchildren who initially did not comprehend photographs depicting

African youngsters whose hands had been cut off by colonialists.

When they were given explanations about the images, the

schoolchildren "switched on to the idea that people can behave

abominably, based on nothing but ethnicity," he explains.

Fleming visits social justice exhibitions around the world and gives

information about the museum's work. As a keynote speaker, he recently

delivered an address about the role of museums at a conference in

Liverpool titled 'Mobilising Memory: Creating African Atlantic

Identities'.

The meeting - organised by the Collegium for African American

Research (CAAR) and a new UK-based body called the Institute for Black

Atlantic Research - took place at Liverpool Hope University at the end

of June.

It began a few days after a white gunman killed nine people inside

the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, in the US state

of North Carolina.

The murders, among numerous incidents of brutality against African

Americans over the past year, sparked a sense of urgency at the

conference as well as heightened the discussion about activism - and

especially the part that writers, artists and scholars play in

preserving and "activating" memory in the struggle for social justice

and human rights.

"Artists, and by extension museums, have what some people have called

a 'burden of representation', and they have to deal with that," says

James Smalls, a professor of art history and museum studies at the

University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC).

"Many times, artists automatically are expected to speak on behalf of

their ethnic group or community, and some have chosen to embrace that

while others try to be exempt," he adds.

Scholarship and activism

Claire Garcia, a professor at Colorado College, says that for a

number of academics "there is no necessary link between scholarship and

activism" in what are considered scholarly fields.

Such thinkers make the point that scholarship should be 'theoretical'

and 'universal', and not political or focused on 'the specific plights

of one group'," she said. However, this standpoint - "when it is

disconnected from the embattled humanity" of some ethnic groups - can

create further problems.

The concept of museums standing for 'social justice' is controversial

as well because the issue is seen differently in various parts of the

world. The line between 'objectifying and educating"' also gives cause

for debate.

Fleming says the National Museums Liverpool, for example, would not

have put on the contentious show 'Exhibit B' - which featured live Black

performers in a "'human zoo' installation; the work was apparently aimed

at condemning racism and slavery but instead drew protests in London,

Paris and other cities in 2014.

"Personally I loathe all that stuff, so my vote would be 'no' to

anything similar," Fleming says and adds,"And that's not because it's

controversial and difficult but because it's degrading and humiliating.

There are all sorts of issues with it, and I've thought about that quite

a lot."

He and other scholars say that they are deeply conscious of who is

doing the 'story-telling' of history, and this is an issue that also

affects museums.

Moral compass

Several participants at the CAAR conference criticised certain

displays at the International Slavery Museum, wondering about the

intended audience, and who had selected the exhibits, for instance.

A section that showed famous individuals of African descent seemed

superficial in its glossy presentation of people such as American

talk-show host Oprah Winfrey and well-known athletes and entertainers.

Fleming says museums often face disapproval for both going too far

and not going "far enough". But taking a disinterested stand does not

seem to be the answer, because "the world is full of 'faux-neutral'

museums", he says.

The most relevant and interesting museums can be those that have a

'moral compass', but they need help as they can "do very little by

themselves," Fleming says. The institutions that he directs often work

with non-governmental organisations that bring their own expertise and

point of view to the exhibitions, he explained. Apart from slavery,

individual museums around the world have focused on the Holocaust, on

apartheid, on genocide in countries such as Cambodia, and on the

atrocities committed during dictatorships in regions such as Latin

America.

"Some countries don't want museums to change," said Fleming. "But in

Liverpool, we're not just there for tourism."

-IPS |