|

Emperor Ashoka at Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh preseved at

Guimet Museum |

Ashoka's recipe for reconciliation

by B.C. Sharma

Given the repeated use of the term 'reconciliation' in Sri Lanka's

post-war context, one is liable to get the impression that it is a new

concept evolved to address the ethnic situation in the island. But

reconciliation is needed not only in Sri Lanka but in all countries

facing conflict and the many troubles created by conflict, especially

prolonged conflict.

In fact, the need for reconciliation was felt in the distant past

also.

One of the first rulers to attempt reconciliation and build an

inclusive society comprising diverse peoples was the great Indian

Emperor Ashoka (269 -232 BC).

Ashoka's seminal contribution to the ideology of reconciliation and

an inclusive society was highlighted by Prof.Rajeev Bhargava, Director

for the Delhi-based Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, at a

lecture delivered in Colombo on July 5.

It was Ashoka's singularly bloody military campaign to annex the

Eastern Indian region of Kalinga in 262-261 BC (100,000 people perished

in it) which made him turn to Buddhism and its message of peace,

non-violence and tolerance. While the war might have been the immediate

trigger for his conversion and adoption of a totally new way of life and

a new philosophy of governance, various kinds of conflicts in the India

of Ashoka's time also had a major role to play in bringing about change.

|

Prof.Rajeev Bhargava |

In his 1925 work 'Ashoka' D. R. Bhandarkar says that in Ashoka's

time, there was a lot of wrangling by competing religious groups.

"Religious fanaticism and sectarianism was rampant," Bhandarkar wrote.

According to historian Romila Thapar, there was the "uncompromising

materialism" of the Charvakas, the metaphysical subtleties of the

Upanishadic thinkers, and of course the multi-layered and complex

ritualism of the Vedic Brahmins.

Rituals and sacrifices

Religion in pre-Buddhist India was dominated by the Vedas. The Vedas

were essentially about rituals and sacrifices meant to increase the

wealth and happiness of the two top castes in the Hindu caste hierarchy,

namely, the Brahmins (ritual specialists ) and Kashtriyas (the ruling

class). The boons sought by the Kshatriyas were quintessentially 'this

worldly' and not 'other worldly'. As for the Brahmins, they held the key

to happiness as only they knew how to conduct the increasingly complex

rituals and sacrifices.

Of course, there was an 'other worldly' aspect to the rituals, but

the 'other worlds' of the Vedas and 'this world' were not independent of

each other. They were part of a single cosmos. In other words, Loka,

Swargaloka and Narakaloka were all part of the same cosmos. Even the

Gods transited between Loka and Swargaloka. One of the goals of the

Vedic rituals was to become 'Amartya' or immortal, which is very

different from wanting to attain the Upanishadic 'Moksha' which is

release from life anywhere.

Apart from those who believed in this Vedic religion, there were

sects which held as being undesirable, acquisition of wealth and other

forms of worldly happiness through rituals and sacrifices. The sect of

Munis believed that salvation would come from self-abnegation,

withdrawal from society and performance of exacting and severe

practices.

The third system of thought was the Upanishadic one. The Upanishads

distinguish between the world (samsara) and Brahman or Atman (the

Ultimate Reality embedded in the universe or in one's inner imperishable

self). The knowledge of the Brahman comes by a search for Gnana

(knowledge) through intellectual exertion. In the Chhandogya Upanishad,

it is clearly stated that rituals and sacrifices or self-abnegation and

self-mortification are useless for attaining Moksha or True Immortality.

Prof. Bhargava says that the Upanishads provide the "axial turn" in

Indian civilization. But still, he notes that the goals of Vedic rituals

and Upanishadic search for the knowledge of the Brahman and attainment

of Moksha are "individualistic" and have nothing to do with "other human

beings or living creatures."

Buddha's Contribution

It was the Buddha who bought in the "inter-personal" element into the

concept of Dharma or good conduct, says Prof. Bhargava. The Buddha even

extended the inter-personal to the animal world. His Dharma was 'social'

inasmuch as it had to do with how people treated each other and treated

animals and other living beings.

|

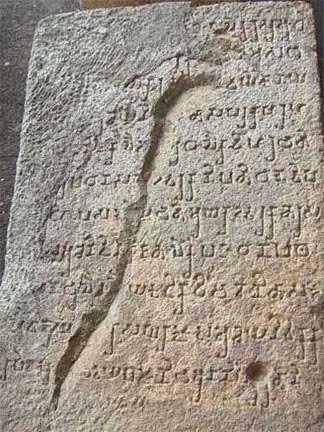

Rock Edict in Dhauli, Odisha, Eastern India |

With the coming of Buddhism, there was a need for public or political

morality, Bhargava observes. The necessity to have systems to arbitrate

between multiple, radically different and rival conceptions had arisen

as society began to advance and diversify as a result of trade and other

interactions with the world. Ashoka's edicts give the recipe for

reconciliation of these divergent tendencies so that they can interact

and mutate each other and in that process contribute to peace,

understanding and growth. Jawaharlal Nehru's concept of 'unity in

diversity' as the goal for India, had its roots embedded in Ashoka's

ideology. It was with a view to establishing his social Dharma that

Ashoka put up rock edicts in thirty places in what is now India, Nepal,

Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan. And they were written in various

local scripts like Prakrit, Sanskrit, and even Greek and Aramaic. The

language was not flowery and formal but simple and direct so that the

masses might understand. It was the beginning of mass communication as

we understand it today.

"At the core of these edicts are a set of precepts about how to lead

a good individual and collective life," Bharagava said. Ashoka took into

consideration and accommodated two realties. One reality was that people

want uniformity in thought, word and deed.

The second reality was the fact of societies being composed of

diverse elements often contradicting and conflicting with each other. He

recognized that diversity was in the nature of things and could not be

wished away not could one wish away the feeling of security provided by

uniformity and sameness. But Ashoka's vision was to see a society that

accommodated diversity because he believed that diversity and mutual

interaction were necessary for the whole society as well as its

constituent parts.

In Edict 7, for example, Ashoka says that all 'Pasandas' (members of

various sects) should dwell everywhere in his empire. He particularly

wanted the leaders of the Pasandas to move about in the empire,

espousing their respective doctrines. This Ashoka did in the context of

sects being persecuted and even expelled en masse in something like

modern ethnic cleansing. He wanted tolerance to be built through

interaction under State patronage. He did not believe in uniformity and

homogenization but in diversity and coexistence based on a true

understanding founded on interaction and discussion. In other words,

Ashoka evolved a new "public morality" based on mutual interaction,

which was, at once, for individual and common good.

Respective doctrines

According to Bhargava, Edict 7 was an attempt to curb the then common

practice among Kings to dispense justice as per their own personal

interest and make them think in terms of the common good, as per a

Dharma which was an 'mmutable moral principle above the King'. The

enlightened King was called a 'Charavarti' in which the Chakra or Wheel

represented the Wheel of Dharma.

|

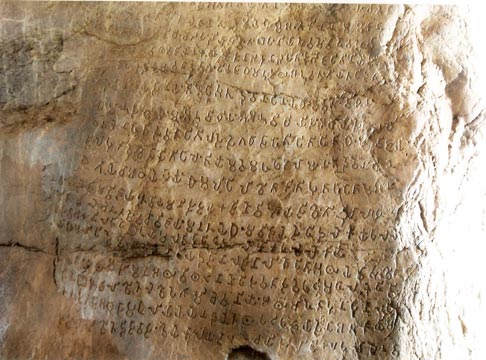

Rock Edict in Kalsi in Dehra Dun district Uttarakhand, India |

However, Ashoka was not oblivious to the common man's need for

rituals. Edict 9 allows rituals and ceremonies on occasions like birth,

marriage, ahead of journeys, sickness and death. But it was his desire

to substitute rituals for the good of man, by State welfare measures. He

urged Kings to dig wells, build rest houses, plant trees and arrange for

the cultivation of medicinal herbs.

"Ashoka said that the Dhammika Dhammaraja must not only be concerned

with upholding the property and family rights of people in society, but

go beyond these minimum obligations and ensure that everyone's basic

needs are met," Bhargava says.

For Ashoka, the 'ceremonies' of Dharma (Dharma Mangalas), are the

proper treatment of slaves and employees, restraint in violence towards

living creatures, and reverence to teachers, Brahmins and ascetics.

To bring the various sects or Pasandas to a meeting point, Edict 12

says that the essentials of all faiths are the same and these essentials

are the common ground for them to meet.

Restrained Speech

For Ashoka, one of the essentials of Dharma is Vachaguti (restraint

on speech) and this is emphasized in Edict 12. He put great emphasis on

right speech because in the oral culture of his day, what was said and

how it was said, could do or undo a relationship for what was uttered

could not be withdrawn. "Words can be a weapon or an elixir. They can

soothe or cause grievous hurt." Bhargava observes that even in this day

and age, speech or oral communication plays a huge role in inter

personal and social communication and well being.

Ashoka says that speech that is critical of others may be freely

made, but only if we have good reasons to make the criticism. Even then,

one's views must be uttered only on appropriate occasions. A critique

must not be done with a view to humiliating others. Edict 12 also

cautions against boasting about one's sect.

According to Ashoka, uncritical and effulgent praise of one's own

sect, can only damage that sect. By offending and thereby estranging

others, one's own Pasanda loses its capacity for mutual interaction and

for changing in a desirable direction, he argues.

Ashoka also emphasizes the need for Bhaava Shuddhi (self

purification). Bhargava interprets this as a call for abjuring ill will

towards others and not just purification of oneself.

To foster interaction and understanding, Ashoka urged the people of

various sects to meet frequently in an assembly or concourse. Underlying

this advice is Ashoka's belief that the ethical foundations of the

various sects are not static but constantly evolving. According to him,

the growth of the sects is crucially dependent on mutual communication

and dialogue with one another rather than existing in isolation. |