|

Short story

The Garden party

... Continued from

25/03/2007 issue

Laurie arrived and hailed them on his

way to dress. At the sight of him Laura remembered the accident again.

She wanted to tell him. If Laurie agreed with the others, then it was

bound to be all right. And she followed him into the hall. "Laurie!"

"Hallo!" He was half-way upstairs, but when he turned round and saw

Laura he suddenly puffed out his cheeks and goggled his eyes at her. "My

word, Laura! You do look stunning," said Laurie. "What an absolutely

topping hat!"

hat!"

Laura said faintly "Is it?" and smiled up at Laurie, and didn't tell

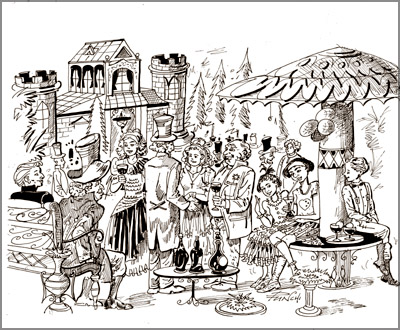

him after all. Soon after that people began coming in streams. The band

struck up; the hired waiters ran from the house to the marquee.

Wherever you looked there were couples strolling, bending to the

flowers, greeting, moving on over the lawn.

They were like bright birds that had alighted in the Sheridans'

garden for this one afternoon, on their way to - where? Ah, what

happiness it is to be with people who all are happy, to press hands,

press cheeks, smile into eyes. "Darling Laura, how well you look!" "What

a becoming hat, child!" "Laura, you look quite Spanish.

I've never seen you look so striking." And Laura, glowing, answered

softly, "Have you had tea? Won't you have an ice? The passion-fruit ices

really are rather special." She ran to her father and begged him. "Daddy

darling, can't the band have something to drink?"

And the perfect afternoon slowly ripened, slowly faded, slowly its

petals closed. "Never a more delightful garden-party ... " "The greatest

success ... " "Quite the most ... "

Laura helped her mother with the good-byes. They stood side by side

in the porch till it was all over. "All over, all over, thank heaven,"

said Mrs. Sheridan. "Round up the others, Laura. Let's go and have some

fresh coffee. I'm exhausted. Yes, it's been very successful. But oh,

these parties, these parties!

Why will you children insist on giving parties!" And they all of them

sat down in the deserted marquee.

"Have a sandwich, daddy dear. I wrote the flag." "Thanks." Mr.

Sheridan took a bite and the sandwich was gone. He took another. "I

suppose you didn't hear of a beastly accident that happened to-day?" he

said. "My dear," said Mrs. Sheridan, holding up her hand, "we did. It

nearly ruined the party. Laura insisted we should put it off." "Oh,

mother!" Laura didn't want to be teased about it. "It was a horrible

affair all the same," said Mr. Sheridan.

"The chap was married too. Lived just below in the lane, and leaves a

wife and half a dozen kiddies, so they say." An awkward little silence

fell. Mrs. Sheridan fidgeted with her cup. Really, it was very tactless

of father ... Suddenly she looked up. There on the table were all those

sandwiches, cakes, puffs, all uneaten, all going to be wasted.

She had one of her brilliant ideas.

"I know," she said. "Let's make up a basket. Let's send that poor

creature some of this perfectly good food. At any rate, it will be the

greatest treat for the children. Don't you agree? And she's sure to have

neighbours calling in and so on. What a point to have it all ready

prepared. Laura!" She jumped up.

"Get me the big basket out of the stairs cupboard." "But, mother, do

you really think it's a good idea?" said Laura. Again, how curious, she

seemed to be different from them all. To take scraps from their party.

Would the poor woman really like that?

"Of course! What's the matter with you to-day? An hour or two ago you

were insisting on us being sympathetic, and now--" Oh well! Laura ran

for the basket. It was filled, it was heaped by her mother.

"Take it yourself, darling," said she. "Run down just as you are. No,

wait, take the arum lilies too. People of that class are so impressed by

arum lilies." "The stems will ruin her lace frock," said practical Jose.

So they would. Just in time. "Only the basket, then. And, Laura!" -

her mother followed her out of the marquee - "don't on any account--"

"What mother?" No, better not put such ideas into the child's head!

"Nothing! Run along." It was just growing dusky as Laura shut their

garden gates. A big dog ran by like a shadow.

The road gleamed white, and down below in the hollow the little

cottages were in deep shade. How quiet it seemed after the afternoon.

Here she was going down the hill to somewhere where a man lay dead, and

she couldn't realize it.

Why couldn't she? She stopped a minute. And it seemed to her that

kisses, voices, tinkling spoons, laughter, the smell of crushed grass

were somehow inside her. She had no room for anything else. How strange!

She looked up at the pale sky, and all she thought was, "Yes, it was the

most successful party."

Now the broad road was crossed. The lane began, smoky and dark. Women

in shawls and men's tweed caps hurried by. Men hung over the palings;

the children played in the doorways. A low hum came from the mean little

cottages.

In some of them there was a flicker of light, and a shadow,

crab-like, moved across the window. Laura bent her head and hurried on.

She wished now she had put on a coat. How her frock shone!

And the big hat with the velvet streamer - if only it was another

hat! Were the people looking at her? They must be. It was a mistake to

have come; she knew all along it was a mistake. Should she go back even

now?

No, too late. This was the house. It must be. A dark knot of people

stood outside. Beside the gate an old, old woman with a crutch sat in a

chair, watching. She had her feet on a newspaper. The voices stopped as

Laura drew near. The group parted. It was as though she was expected, as

though they had known she was coming here.

Laura was terribly nervous. Tossing the velvet ribbon over her

shoulder, she said to a woman standing by, "Is this Mrs. Scott's house?"

and the woman, smiling queerly, said, "It is, my lass." Oh, to be away

from this! She actually said, "Help me, God," as she walked up the tiny

path and knocked. To be away from those staring eyes, or to be covered

up in anything, one of those women's shawls even. I'll just leave the

basket and go, she decided.

I shan't even wait for it to be emptied. Then the door opened. A

little woman in black showed in the gloom. Laura said, "Are you Mrs.

Scott?" But to her horror the woman answered, "Walk in please, miss,"

and she was shut in the passage. "No," said Laura, "I don't want to come

in. I only want to leave this basket. Mother sent--" The little woman in

the gloomy passage seemed not to have heard her. "Step this way, please,

miss," she said in an oily voice, and Laura followed her. She found

herself in a wretched little low kitchen, lighted by a smoky lamp. There

was a woman sitting before the fire.

"Em," said the little creature who had let her in. "Em! It's a young

lady." She turned to Laura. She said meaningly, "I'm 'er sister, miss.

You'll excuse 'er, won't you?" "Oh, but of course!" said Laura. "Please,

please don't disturb her. I - I only want to leave--" But at that moment

the woman at the fire turned round.

Her face, puffed up, red, with swollen eyes and swollen lips, looked

terrible. She seemed as though she couldn't understand why Laura was

there. What did it mean? Why was this stranger standing in the kitchen

with a basket? What was it all about? And the poor face puckered up

again.

"All right, my dear," said the other. "I'll thenk the young lady."

And again she began, "You'll excuse her, miss, I'm sure," and her face,

swollen too, tried an oily smile. Laura only wanted to get out, to get

away. She was back in the passage. The door opened. She walked straight

through into the bedroom, where the dead man was lying.

"You'd like a look at 'im, wouldn't you?" said Em's sister, and she

brushed past Laura over to the bed. "Don't be afraid, my lass," - and

now her voice sounded fond and sly, and fondly she drew down the

sheet--"'e looks a picture. There's nothing to show. Come along, my

dear." Laura came.

There lay a young man, fast asleep - sleeping so soundly, so deeply,

that he was far, far away from them both. Oh, so remote, so peaceful. He

was dreaming. Never wake him up again. His head was sunk in the pillow,

his eyes were closed; they were blind under the closed eyelids. He was

given up to his dream.

What did garden-parties and baskets and lace frocks matter to him? He

was far from all those things. He was wonderful, beautiful. While they

were laughing and while the band was playing, this marvel had come to

the lane. Happy ... happy ... All is well, said that sleeping face. This

is just as it should be. I am content.

But all the same you had to cry, and she couldn't go out of the room

without saying something to him. Laura gave a loud childish sob.

"Forgive my hat," she said. And this time she didn't wait for Em's

sister. She found her way out of the door, down the path, past all those

dark people. At the corner of the lane she met Laurie.

He stepped out of the shadow. "Is that you, Laura?" "Yes." "Mother

was getting anxious. Was it all right?" "Yes, quite. Oh, Laurie!" She

took his arm, she pressed up against him. "I say, you're not crying, are

you?" asked her brother.

Laura shook her head. She was. Laurie put his arm round her shoulder.

"Don't cry," he said in his warm, loving voice. "Was it awful?" "No,"

sobbed Laura. "It was simply marvellous. But Laurie--" She stopped, she

looked at her brother. "Isn't life," she stammered, "isn't life--" But

what life was she couldn't explain. No matter. He quite understood.

"Isn't it, darling?" said Laurie. |