Historicity of a legendary genius

by Aravinda Hettiarachchi

'There was an aesthetic side to my life, and an unsophisticated side

as well. I began my career in cinema during an irrational era, when this

country had not educated its film artistes in this particular genre yet. 'There was an aesthetic side to my life, and an unsophisticated side

as well. I began my career in cinema during an irrational era, when this

country had not educated its film artistes in this particular genre yet.

Therefore we didn't have an appropriate way of learning conventional

things. In those days I was still basically mesmerized by theatre. I was

very attracted by Laddie Ranasinghe's acting. He was a great actor. I

had also heard of some performing artistes at that time such as Romlas

de Silva, Mark Samaranayake and Rukmani Devi.

While I respected them and was awed by their acting, I preferred to

watch European films. Back then, the task of educating ourselves in

cinema was directed towards England because we were familiar with their

language only.

Yet we didn't even think of visiting England due to the cost of a sea

passage at the time. I think our opportunity of going to England was

curtailed. They always used our economic incapacity as an excuse as well

as a justification to say 'no' to us.'

- Gamini Fonseka

***

Dinesh Priyasadh is one of the more noteworthy popular film directors

in this country who has made high action films with modern special

effects. He was also an intimate friend of Gamini's in the latter stages

of the actor's life.

According to Priyasadh, Gamini wasn't an actor who took a lot of time

to embody a mood for a particular character. He found his character at

the exact flash of the camera's call to 'action!' He balanced a perfect

integrity between real life and the cinematic dream world.

Therefore he was always ready to imbue new meanings in the actual

instant of the rolling of the camera "as an actor who always acted

within a given framework. He was a human being of colossal talent within

a panoply of aesthetics, capturing the diversity of lifestyles extant in

this society.

He was not rigid about mere language but was a practical actor who

acted with immeasurable thought, always portraying the subtleties of

characters representative of our neocolonial society successfully.

Perhaps this is what we have to derive from Gamini's acting style, as

we create an cinematic ethos of our own after 500 years of colonialism.

Yet did Gamini have the capacity to locate his great acting ability

within this historical confrontation?

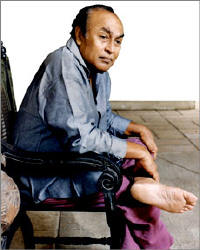

Film legend Sembuge Gamini Shelton Fonseka was born in 1936 into a

typical upper-middle class family surrounded by a milieu entrapped

between development and underdevelopment, Christianity and Buddhism,

English and Sinhala, in an era where people were encouraged to compile

their main cultural and aesthetic disposition through England and India.

He spent his first stages of boyhood (with his primary education from

Presbyterian Girls' School, Dehiwala and secondary education from St

Thomas College in Mt. Lavinia) in a colony countering the winds of

change, yet trying to free ourselves from English supremacy within a

constitutional struggle parallel to India's material struggle for

freedom (within an economic condition where the East Indian Company had

to leave India due to India's political struggle of nationalism, and

there was no use value of keeping Sri Lankan economy under British

administration any longer).

He grew up in a repressed psychological family environment, where his

astrologically-bound mother did not permit him to stay outside at night,

and was ever vigilant even when female cousins visited his house,

whereas his macho type father was a businessman and a chandiya in both

the orthodox and unorthodox senses, as well as being a cherished lover

of aesthetics.

Gamini, highly respected as a trilingual (Sinhala, Tamil and English)

character actor, was also a painter, writer of lyrics, and lover of

music in its vast parameter.

Furthermore, he was an enthusiastic technical assistant and assistant

cinematographer, screenwriter and film director who navigated his

creative career midst the soft and profound passions of human kind in

this society, sometimes making strong denunciations about violence

against nationalities, castes and nikayas.

He was a man who used to deliver such lines just chatting with his

mates, such as, "To me a man is a man, whatever the colour of his skin,

whatever the language he speaks, whichever gods he worships, he is the

kin of all men the world over...")

Gamini started his career in film before Rekhava, with the

documentary Pol Vagaava (about a coconut plantation in Sri Lanka)

directed by Lester James Peiris,where he acted as two converse

characters: an old man and a young fellow.

This was his first encounter with Lester, and it motivated him to

connect to films as a main actor. Then again he acted as two differently

aged characters (while he was in his 20s) in Kenneth Hume's English film

Elephant River.

Hume was surprised with this diversity in his acting and asked him,

"At which school did you learn to act'" Gamini replied, "I did it on my

own. I learned in my own school." After he acted in Elephant River,

Lester James Peiris decided to select Gamini for the supporting role in

his second film Sandeshaya.

In the early 1950s, Gamini's cinematic endeavour as an assistant

director was further developed with the chance to work on David Lean's

English war propaganda film, Bridge on the River Kwai. And again in

1955, he was assistant director on Rekhava, as well as acted in a small

crowd scene in that film. Lester used to say later that, 'He was the

most disciplined assistant director in my whole career!'

The philosophy of a local ethos in Gamini's acting method emerged

through classical Sinhala films (such as Nidhanaya - a local masterpiece

which can still be rated alongside any classic in the world) as well as

through the local "heroic" films (such as Chandiya, which according to

Priyasad contains a valuable element of heroism for our society, blotted

out now due to the servile characters within the film industry as well

as in the society).

Among these two categories of film, I suppose, both were equally

significant and important in the sense of archiving an acting method of

our own as well as of the rise of the film industry.

Gamini maintained a method remarkably different from the non-method

actor Vijaya Kumaratunge (a hugely popular icon of the time) and the

immeasurably methodical actor Solomon Fonseka (the only person in Sri

Lanka with a doctorate in method acting, and one of the most "unfamous"

individuals to even some who worked in the film industry).

Thus I deduced that Gamini was not such an actor of extremes, but an

actor of praxis (fusing these two extremes) with an acting method

relevant to our society, vis-...-vis a sense of building a valuable and

competitive film industry (now reduced to merely a dream due to

misadministration after 1977's absurd radical economic lobotomy). Hence

it is awkward to frame his acting method in Eurocentric circumlocutions

such as, He was a carbon copy of Marlon Brando' or whatever.

Gamini's film acting was mostly multilayered, with his personal

improvisations based on various aesthetic forms such as painting, music,

literature, etc., and through vast observation focusing on different

cultural, national behaviours of a complex neocolonial society with

different classes, and furthermore with a precise technical know-how to

move and place the film camera.

Therefore anyone, who having endured 500 years of colonialism,

locates Gamini's acting methods solely within the modern acting forms of

highly Eurocentric settler societies (uttering words such as "He is

another Brando"), would surely err off target.

"There are people who have an in-depth knowledge of acting styles in

the world. Yet mere knowledge will not project an impression or an

expression of a character. Therefore a knowledge of acting alone is not

enough. Yet if by using this knowledge, you could practically develop

something inside you ... then you could leave something solid for your

country. - Gamini Fonseka

Gamini was of a generation who confronted the challenge of

discovering a local method of acting after the shift in English colonial

strategy (post-1948), after the decline of carboncopying the South

Indian method of melodramatic acting (just after the 1950s, with Lester

James Peiris' Rekhava, the first to be filmed outdoors in Sri Lanka).

Of most of the talented actors of this generation, Gamini's

exceptionality was that he built a polyphonic acting style relevant to

Sri Lanka's national and cultural variety regardless of whether it was

Sinhala or Tamil, Goigama or Rodi, urban or rural, in the classical and

popular films of our country.

This could nevertheless be totally consigned within the European

conceptuality of acting, yet his technical apprenticeship was highly

influenced by both India and Europe.

The technical equipment or "the means of production" of cinema

(specially the film camera equipment sent to South Asia not to encourage

reasonable autonomy but to subject us to further colonialism) was born

within the European arena after the decisive historical juncture of the

industrial revolution.

Therefore this technology did not have a direct historical connect to

our pre-colonial era as one of our own "means of production."

The first film actors to develop an acting method of our own despite

the reactionary trend of imitating European and South Indian styles in a

carbon-copy approach, may be placed in two categories: The classical

actors (D. R. Nanayakakara, Joe Abeywickrema , Henri Jayasena, etc.) and

the entertainers (Ananda Jayaratne). Yet Gamini was one who determinedly

developed a practical method of acting (with the rationality of building

a better film industry for the country) within these two categories

successfully, by carefully identifying our own locality within the

meanings of both main languages (Sinhala and Tamil), and addicted to

keenly and shrewdly observing real characters and their behaviour in our

society, rather than merely imitating actors in Europe or South India.

A neo-renaissance of Sinhala cinema had commenced with Rekhava, the

first to be filmed outdoors incorporating a realistic acting style in

1955, a film totally different to the wierd masala-mix melodramatic

style of films carboncopied from South Indian cinema.

The refinement of cinematic culture touching Sri Lanka paralleled the

Indian filmscape of Bengal, with Shanthinikethan influencing the genius

of filmmakers such as Satyajith Ray who revealed Asian society in its

real ethos. This refinement of cinema in Sri Lanka was spread through

such bilingual middleclass filmmakers, as well as the filmmakers brought

up under the limiting 'Sinhala-only' educational policy.

Filmmaking at that time was, therefore, not a cultural practice of

ordinary people. Gamini also began by walking in as a trilingual

middleclass film artist within this flow. Yet later he developed a

classical acting style beyond this flow, which possessed even more human

characters relevant to Sri Lankan society.

Additionally, Gamini was also engaged in the new culture of popular

film, changing his previous ways of acting into a popular style of our

own, which especially boomed in the early 1970's, mainly projecting a

heroic figure for the common people.

He was also equally involved in bringing up most of the ordinary

people of great talent into our cinema field. Thus he was one of those

geniuses (as an actor) who engaged in between both classical and popular

zones of our film industry successfully.

After 1977, as anti-national constitutional changes started blotting

out the functioning of the state, the whole system of mass media in Sri

Lanka accelerated into a certain type of chaos.

Therefore, within that jagged transition, cinematic art in Sri Lanka

also started shifting its previous ethos, without proper guidance, into

withstanding the complicated challenge of restructuring our aesthetic

culture within a system of privatized endeavour.

Thus those pre-'77 cinema artists, even geniuses like Gamini, were

unable to face this challenge due to the sudden fast inflexible

imposition of Euro-US capital into the country. Nor could they face the

institutional hypocrisy created through such political pollution and

misguidance.

While Euro-Us capital started crushing our sovereignty into a more

impractical existence, especially after 1977, it also started to blur

our ethical standards of cinema with directly market values.

Hence a new generation, almost uneducated in the previously held

values and standards, started immersing themselves in the new

misadministration of aesthetics and cinema.

Consequently, by the 1980s, the cinema industry arrived at a stage of

confusion, which began by crucifying previously classical filmmakers

such as Gamini Fonseka, Lester James Peiris, Tissa Abeysekara,

Dharmasena Pathiraja, Vasantha Obeysekera, Dharmasiri Bandaranayake,

etc., as well as those such as Titus Thotawatte and Sena Samarasinghe

from the popular cinema.

This haemorrhaging, for example, significantly did not allow

Dharmasena Pathiraja to create a new film for twenty years and reduced

the amount of films Gamini acted in per year rapidly. This was also a

sign of the devaluation of the whole pre-77 aesthetic culture of Sri

Lanka, even as India was still changing its cinematic values with

reference to this so-called neo-liberalism under their own

constitutional valuing of autonomy.

With rising devaluation by this neo-Disneyland, some previously

quality filmmakers betrayed their policies, changing into "some thing or

another," to just settle down within the system without even a proper

evaluation of this quick-cut transition.

Therefore, at this crucial moment of neo-crucifixion, those beings

who were true to their creative art form, such as Gamini Fonseka, chose

death by slow suicide rather than by changing their selves into mere

clowns with an exchange value, always reappearing to shill some awful

product on TV commercials endlessly.

You may retort that, "You are mad! It was a natural death, even the

coroner's post-mortem report says so!" Yet I will tell you a story: When

Hitler caught a musician who wrote compositions against his ideology,

what did he do? He didn't shoot him to death.

He just shut him in a room, and blasted him with cacophonous tunes.

In a situation such as this, of killing one's musical soul, what should

an authentic musician do?

Commit his body to musical suicide? Thus some people in this society

are killed directly by a bullet or whatever. It is a direct and honest

way of killing. And some people have almost totally relegated suicide to

a so-called naturally slow death.

So, what is the difference? Are we proud enough of our own country,

even now, to nurture youngsters who prefer an authentic cinema?

"Hey Amaranath, I chatted with that chap Gamini, who acted as

Jinadasa in Gamperaliya. He appears to be a great youngster, with lot of

talents and knowledge. He should have been born in India. India needs

these kinds of actors. He is invaluable to Sri Lanka!" Sathyajith Ray to

Amaranath Jayatilake. |