Master mason

by G. Shankar

I was a student just out of school in Kerala when I first met Laurie

Baker. A friend had invited me over to visit the site where, he said, a

foreigner was building a house for his family. There I saw this

fair-skinned man engaged in a heated argument with his client, my

friend's father, a mathematics professor. I was a student just out of school in Kerala when I first met Laurie

Baker. A friend had invited me over to visit the site where, he said, a

foreigner was building a house for his family. There I saw this

fair-skinned man engaged in a heated argument with his client, my

friend's father, a mathematics professor.

Among other things, the professor wanted a cylindrical shape for his

home, to get the benefit of maximum space, and six bedrooms, one each

for his five sons and the other for himself and his wife. The argument

was about the bedrooms.

I still remember Baker asking the professor, "Look, Mr. Namboodiri,

you have five sons, all of them brilliant students. They will all start

flying very soon and will go away.

Finally, an old man and an old woman will be all alone in this house.

Are you sure that you still want six bedrooms?" The professor was

adamant. He said, "Yes, I do want six bedrooms. As long as my sons are

with me, they should have their own rooms." I was fascinated by the

discussion that Baker had with his client that day. It was my first

encounter with the man. I had never heard about him before.

It was much before I knew anything about architecture or decided to

make it my vocation. Several years later, I visited the house that Baker

had built for my friend's family. The professor was long gone. The

children had all flown away. Their mother, now quite old, was alone in

that three-storied house. There were cobwebs in every nook and corner,

on the roof and on the spiral staircase. Clearly, nobody climbed

upstairs any longer.

I told her that I had first met Baker on that very site, years

earlier, when he had been warning her husband about the futility of

building a bedroom for each of their five sons. The old woman clasped my

hand and cried for a while. It was one of my formative impressions about

Laurie Baker. Later, I went on to study architecture.

In college, we were exposed to a range of architectural styles. We

were taught an excess of them really, Buddhist, English, Victorian,

Edwardian, Byzantine, Columbian, you name it. But we were never taught

how to make a small house, within five cents of land, for five adults,

and with only Rs. 50,000. This is the Indian reality. Instead, we were

taught how to build buildings in unlimited time, with unlimited budgets.

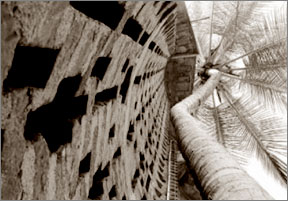

But, fortunately, by then, "Baker buildings" were happening all

around us. The shape of those buildings used to fascinate us. It was

from then on that I started taking note of Baker professionally, as an

architect.

The prestigious low-cost complex of the Centre for Development

Studies (CDS) in Thiruvananthapuram had already been built by Baker and

became a rallying point for many of us students and architects.

During vacations, we used to frequent all the Baker buildings, to

observe his art at close quarters. It was not just the miraculous range

of new building materials used by him that fascinated us. The rare

beauty of the interiors, the spaces that he created where light and air

flowed freely, all of it was a new experience for us.

After graduating, I went to Delhi. There, I had a peep into the other

side of architecture. Baker took a number of factors into consideration

before he decided the architecture of a building - the site, the

climate, the client, the children and many such criteria. But in Delhi,

I was introduced to architecture that was totally faceless. You did not

need to know who the client was. It was as if you were building for

anybody. It was architecture without values. It was a quagmire of

corruption, pretensions and ego.

It was a different platform altogether. In about three years, I

decided to go back to Kerala and Baker. I found that it was the right

path, the one along which Baker had opted to walk alone. But that itself

was a problem. Laurie Baker used to work alone. He used to describe the

box of instruments that he carried with him as his "office". It was a different platform altogether. In about three years, I

decided to go back to Kerala and Baker. I found that it was the right

path, the one along which Baker had opted to walk alone. But that itself

was a problem. Laurie Baker used to work alone. He used to describe the

box of instruments that he carried with him as his "office".

There were a lot of people who wanted access to Baker. But Baker was

not available. I felt, therefore, that some kind of a democratic

movement should be formed to foster Baker's technology, to take it

forward.

That was why I decided to start the Habitat Technology Group in

Thiruvananthapuram. For me, it was a sort of a political action too, for

people-friendly architecture, for relating to people in a better way

and, especially, for focusing on the poor - ideas dear to Laurie Baker.

I used to meet Baker at times. But it was still a very distant

relationship. I was never really close to Baker then. I decided I needed

to study more and chose to go abroad for my masters. Once again Baker

became the inspiration. I studied at the very same school where Baker

had once been a student (in 1937), the Birmingham School of

Architecture.

As I was leaving for England, Baker gave me a reference letter, in

which, among other things, he said of me, "I know of no other young

person in India who can take this technology forward." To me, it was a

blessing from a great master, which came quite early in my career.

After I came back, I used to frequent the meetings and conferences

attended by Baker and listen to his speeches and lectures. As I moved

closer to him, I realised that there was no conflict between the man's

words and deeds. His sleeping bag, for instance, was made of khadi. He

wore only simple clothes and simple shoes.

There is a well-known anecdote about Baker's meeting with Gandhiji in

Bombay, soon after he came to India (from China where, during the Second

World War, he had been a British missionary architect and health worker

looking after people suffering from leprosy).

The first thing that struck Gandhiji about Baker was his shoes, which

he had fashioned out of pieces of waste cloth. As the story goes,

Gandhiji took the "Chinese cloth shoes" in his hands and, soon after

Baker had demonstrated how they were made, asked Baker if he could stay

back in India and not return to his native England.

Baker was truth personified. I have seen no one else like him. His

life itself was a message. I have not met Gandhiji. So, for me, Baker

remains the only true great man I have known. His words, clothes, humour,

buildings, everything personified his ideas and ideals. His concern for

nature, for trees, for the common people, for India, for Kerala was a

genuine, deep concern.

I still remember an occasion when he was at work in a housing colony

for Indian Administrative Service officers in Thiruvananthapuram. He

used to go there every day. The buildings were all of different shapes

and sizes.

It was really a museum of different buildings, a beautiful mixture of

shapes. But one fine morning when he arrived there, he saw a young mango

tree being cut down. He did not say a word but quietly went back to his

car.

He never returned to the IAS colony again. Circumstances force people

to make compromises. Dilutions do happen in our lives. But Baker was

uncompromising in his convictions.

That is truly the trait of a great man. He would not compromise on

his beliefs. I have never seen an architect like him. The man was very

clear about what he wanted. The cutting down of a tree hurt him so much

that he had to leave immediately, never to come back.

His clientele included a range of people, from the humble fisherman

to the Chief Secretary of the State. But he never differentiated between

people. He used to say, "I never build for classes of people, HIG [high

income group], MIG, LIG, tribals [tribal people], fishermen and so on.

But I will build only for a Matthew, a Bhaskaran, a Muneer, or a

Sankaran." Baker never built for unknown people.

He built for people with names and faces. He believed that every

person had a name, a face and a personality. Another delightful facet of

the man was his uncanny sense of measurement.

He would go to a building site with a bunch of pegs and a bundle of

strings in his pocket and would make the measurements himself, using his

feet. He never worked from drawings.

He used to go to the site and discover things. At the site, he would

say, suddenly, "Why don't we put the window here so that it will open

out on to that particular view." As I said earlier, Baker often worked

alone. He was also a good mason.

On the day he won the World Habitat Award (1992), I was so happy that

I had to be the first man at his door to congratulate him. I reached

there early in the morning, at seven, but Baker had already left. His

wife told me I could catch him at his worksite, a few kilometres away.

When I went to the site, there, to my amazement, was Baker, perched

precariously on a sloping roof winding wires, immersed in his work. I

have seen such an attitude towards one's karma only in one other person,

E.M.S. Namboodiripad.

Laurels and awards hung lightly on him. At several places in north

India, in New Delhi, in Ahmedabad, I have seen people revering Baker.

But not in Kerala, where he made his home. He was never invited to teach

students. He was ignored by the architects' bodies. Some even

"pooh-poohed" him as a "brick-layer". His greatest wish, to be an Indian

citizen, was granted late, only in 1988. He was subsequently awarded the

Padma Shri.

The British government honoured him with the Order of the British

Empire. But for Baker, becoming an Indian citizen was his only true

achievement. Baker came East from England as a volunteer architect

attached to a mission during the war and lived an amazing life in China

and north India looking after leprosy patients and building hospitals,

schools, libraries, ashrams and homes.

He met Elizabeth Jacob, the Malayalee doctor who later became his

wife, while nursing patients in Mumbai at her brother's hospital. Baker

arrived in Kerala 35 years ago and immediately struck a chord with

ordinary people, soon after he began demonstrating that homes could be

built for even Rs.3,000.

Baker was a great cartoonist. He used to see the social reality of

India with the characteristic sense of humour that was also the most

endearing quality about him. Perhaps more than for his architecture,

people loved him because he was a wonderful human being.

(As told to R. Krishnakumar in Thiruvananthapuram.)

G. Shankar is the founder and chief architect of Habitat Technology

Group, a prominent organisation in the building sector in India, which

draws its inspiration from Laurie Baker's architectural style and

philosophy.

Courtesy: The Hindu |