African 'tree of life' recast as European superfruit

In Senegal, villagers have always known about the health benefits of

baobab fruit, which only now have been discovered by Europe in what

could spell magic for localities like Fandene.

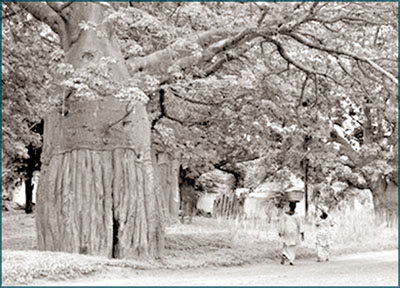

The ancient, hardy species also known as the "tree of life" is

scattered across the African savannah, some said to date back to the

time of Christ.

Locals use nearly every part of the tree, whose processed fruit was

approved for European import last month.

"You use the monkey bread fruit if you have a belly ache," said

farmer Aloyse Tine, using the local name for baobab fruit. "If you're

tired you eat the leaves, they are good for you."

The seeds can be pressed to extract oil used for cooking and the bark

can be used to make ropes. The seeds can be pressed to extract oil used for cooking and the bark

can be used to make ropes.

In the past, the hollow bark was also used to bury "griots", a

special West African caste of poets, musicians and sorcerers.

Farmer Tine, like others, used to lug his fruit to sell in the market

in the nearby town of Thies.

Three years ago, he started selling instead to a Senegalese company

run by three Italians. It is the country's only industrialised producer

of dried baobab fruit pulp, which it exports for use in cosmetics and

certain dietary supplements.

The new income has already made changes. It "allows me to send my

kids to school," he said.

Enter a non-governmental organisation that focuses on developing fair

trade and environmentally sustainable natural products.

Sensing potential, it launched in 2006 the process that would open

European Union markets to this nutritious African oddity. Under EU

rules, any "novel" food - one not commonly consumed in Europe before

1997 - requires special approval for use in the 27-member bloc.

"Approval for the baobab is fantastic news for Africa," said the

organisation's Cyril Lombard after the EU decision.

"Opening the European market to this product will make a real

difference to poor rural communities there, offering them a potentially

life-changing source of income."

One of these is Thiawe Thiawe, where 41-year-old Delphine farms some

20 baobab trees scattered outside her house.

"I've collected the fruits since I was a little girl with my

grandmother," she told AFP. Like Tine, her life is a little easier since

she started selling to the company rather than hawking her own goods.

"It's better to sell here than there, you don't have to wear yourself

out going to Thies."

The company says it already sees a spike in interest from Europe,

where the pulp will likely be used in cereal bars and health drinks.

"Now we collect 150 to 200 tonnes of baobab fruit each harvest. In

the last weeks there has been an explosion in demand," Laudana Zorzella

told AFP at the factory in Thies.

"We are thinking we will need a much bigger harvest next time," she

said. "In Senegal alone, we estimate we could collect 13 thousand tonnes

of fruit."

But what can baobab fruit, also known as monkey's bread, bring to

health-conscious Europe?

According to the International Centre for Underutilized Crops at the

University of Southhampton, the baobab is "a fruit of the future", rich

in vitamin C, B1, B2 and calcium and chock-full of anti-oxidants.

In Senegal, its pulp is mostly used to make Bouye, a milky juice made

by boiling the pulp and seeds with water and sugar.

Some scientists calculate the fruit has three times as much vitamin C

as oranges and has more calcium than a glass of milk. And the tree is

well adapted to arid (harsh) conditions, tolerating both drought and

poorly drained soil, and is fire resistant. Also known as the "upside

down tree" for its bulbous trunk and spindly branches that look like

roots, it can grow to be hundreds if not thousands of years old.

A study for the NGO conducted by the Natural Resources Institute in

Britain suggested that wild harvesting of baobab fruit could generate

trade of up to one billion dollars (640 million euros) a year for

African producers.

Some environmentalists fear such commercial exploitation could lead

to extinction of the iconic tree. But Zorzella dismissed this, stressing

that her company uses only the fruit and leaves the tree intact. "And if

it becomes an important revenue the farmers will know that they have to

protect the tree," she said.

In Fandene, Aloyse said this lesson has already been learned. As new

baobabs sprout spontaneously, they are protected and allowed to grow.

"There are cattle herders that cut the leaves (to feed their animals)

but we are starting to stop them now. That's not good because we need

the trees to produce fruit," he said. After the EU's approval,

"everybody is asking for our products so they can test them," Zorzella

said.

- AFP

|