Public vs private poetry in Sinhala

Analysis of Prof. Somaratne Balasuriya’s Lokaya

Miyayai (The World Dies):

By Ranga CHANDRARATHNE

“Honest criticism and sensitive appreciation

is directed not upon the poet but upon the poetry. If we attend to the

confused cries of the newspaper critics and the susurrus of popular

repetition that follows, we shall hear the names of poets in great

numbers…” Tradition and the Individual Talent –T. S. Eliot

In my opinion, the contemporary Sri Lankan poetry, particularly the

Sinhala poetry is at a cross roads as we enter the second decade of the

21st century. With the advent of digital publications; a medium with no

restrictions that offers both young and old poets to write and publish

their poetic emotions instantly, writers push them through the Internet

for global consumption ignoring national boundaries.

Still today, the 1970s poets such as Udeni Sarathchandra, Ratna Sri

Wijesinghe etc. continue to publish poetry, and we have our diasporic

poets from overseas writing in Sinhala, and of course young Sri Lankan

bloggers who write whatever they want for public consumption. Their IT

enlightened readers come out with instant responses and feedback, and

most of the time limited to slang like, niyamai, elakiri, and marai

neda? (perfect, milk, perfect isn’t it?) etc.

|

Prof. Somaratne Balasuriya |

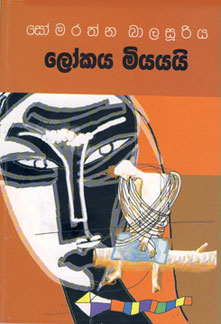

Amongst all these manic activities on Sinhala poetry, it is inspiring

to read the latest collection of poetry by Prof. Somaratne Balasuriya,

entitled Lokaya Miyayai (The world dies) and needs to be viewed as an

important contribution to the contemporary Sinhalese poetry. The author

has used both blank verse and conventional poetry to convey his ideas in

this collection which consists of 50 poems. Amongst all these manic activities on Sinhala poetry, it is inspiring

to read the latest collection of poetry by Prof. Somaratne Balasuriya,

entitled Lokaya Miyayai (The world dies) and needs to be viewed as an

important contribution to the contemporary Sinhalese poetry. The author

has used both blank verse and conventional poetry to convey his ideas in

this collection which consists of 50 poems.

The poems in the collection could be categorised into different

themes; contemporary society and events, nostalgia, revisiting important

milestones in the poet’s life, and the poet’s critical views on society

at large.

Apart from the long titled poem ‘Lokaya Miyayai’, the other poems in

the collection are those which the author had penned from time to time

while engaging in public activities in diverse capacities as stated in

the preface.

Having read this collection, I managed to get hold of what I presumed

to be his maiden collection, entitled Mama saha Numba (You and I) which

was first published in June 1969 with a second edition in 2000. It also

contains a poem with the title ‘Lokaya Miyayai’. What immediately struck

me was that in this collection, then a young poet Balasuriya has looked

inwards and written very private poems as opposed to public poems.

Though we had debates that began in the 70s looking at the purpose of

Sinhalese poetry, and issues dwelling with socialist realism, I don’t

believe that we had a productive debate on whether our poets have

written private versus public poetry, even examining the work of our

foremost poet Gunadasa Amarasekara.

Private and public poetry

Primarily, private poems focus on inner thoughts, faded love affairs,

or very private experiences a poet or poetess write on. As opposed to

private poems, the public poetry focus largely on socio political themes

and in this collection, poet Balasuriya has focused both on private

themes but what comes across powerfully is his insightful expressions on

public themes, and the long poem Lokaya Miyayai is no exception.

One of the private poems in this collection is the reflection of a

meeting with a former fiancée as captured in a poem entitled ‘Dashaka

Hatarakata Pera siti Pemvatiya’ (The fiancée four decades ago).

The poet attempts to capture not only the changes that have taken

place over the years between him and the girl friend who visits him as

an old woman. The old woman not only represents the poet’s past but also

the milieu in which he had a relationship with her, four decades ago.

The girlfriend four decades ago

This is how the first two stanzas of the Sinhala poem read and a line

by line English translation of the full poem follows:

Dorata/ semin/ semin/ thattu karai/ kisivek/ dora siduren/ bala sitee

ohu.

Ithiriyaki ea/sudu paha sariya/dirapath muhune/mathuwa etha/digati

nasaya//dora desatama yomuwoo/muwatha motawoo balamaki/Gilunu denetha

thula/nalala dekammul/rali mathu wee etha/vivara muwa depasa/edee yai

iri dekak/Watha rali mohothakata/vinda ma/wesunu dora

samaga/mandasmithiyaki.

Someone

Taps on the door

Slowly

Slowly

He looks

Through the keyhole.

She is a remnant

A white Saree

Rather debauched face

A blunt gaze

Focused on the door

The eyes sunken in the sockets

Wrinkles on the forehead

On her cheeks

Two lines drew in the corners

Of the opened mouth

For a moment

I catch the wrinkles on the face

Smiling

At the closed door.

The rest of the poem reads:

She could not be a beggar

For she dressed well

Could be a destitute

Seeking aid

With or without a list in her hand.

Couldn’t she be a

sneaky old woman?

Roaming from house to house

And engaged in espionage

A knock

Again at the door

Slowly, barely audible

I opened the door

Two small crystal balls trapped

In the bottom of her eyes

Aimed at me

Could you identify me?

The girl you loved

Forty four years ago

I am.

Forgive me

I thought of seeing you today

One day before I breathe my last

She climbed up the steps

With my help

I made her sit as a

child on the sofa

Are you happy or sad?

How about your children?

The children have not left me

They inquire my wellbeing

Asking me to leave the country

They should not be in my care

In a world which has

become a village

Okay for me to enquire

whether you

Feel lonely

I don’t feel loneliness

I live recalling good deeds

Of my past

Forgive me

For inability to come to see

Her dead face

I donated the excess

And live happily

Until my death

But now

I must be off.

The time has devoured everything; love, relationships and the youth

of both the narrator and his ex-girlfriend who now spends her twilight

of life alone in Sri Lanka while her children live abroad. For the poet,

the old lady is only a ‘remnant’ of the past. The changes of time have

been depicted through the corporal changes of both the narrator and the

woman. The poet effectively hints that the narrator remains a bachelor.

Where the poetic diction has gone?

The ex-girlfriend is an important milestone in the narrator’s life

and he recalls not only the happy moments they spent together, but also

captures the physical changes that took place over the years.

After forty-four years, the narrator and ex-girlfriend spend their

evening of life under different circumstances. In a way, both of them

are alone, the woman’s children have migrated and the narrator is still

a bachelor.

Despite this very private experience, a major deficiency in this poem

is the poet’s incapacity to convey this experience through poetic

diction rich with metaphors and images. When he provides us with images,

they have no novelty or freshness. For example, see:

Two small crystal balls trapped

In the bottom of her eyes

Aimed at me

However, one of the significant aspects of this collection is that it

deals with diverse issues and themes which represent different aspects

of life in the post independent Sri Lanka. Although they may sound an

individual’s private experiences and views, they bring back the seminal

signposts of the milieu with its social upheavals and changes.

The poem ‘Vivaha yojanava gena aa dukkha domannassaya’ (The sadness

that the marriage proposal brought about) deals with the issue of

marriage which still is a powerful social institution in contemporary

Sri Lanka. . In the conservative segment of Sri Lankan society, parents

still believe that it is their prime responsibility to find partners for

their grown up children. In this poem, the poet relates an incident

where a female nursing student responding to a marriage proposal

advertisement. Like most marriage proposals, appearing in newspapers,

this one has been put up by parents of a bachelor seeking a prospective

bride and the female nursing student responds instead of her parents:

The sadness that the proposal brought about

The telephone rings

Forgive me

I am a third year female

Nursing student

I read in the Sunday newspaper

A partner is sought for your son

Neither my mother nor father

Could afford to call,

You, such an erudite and

Famous person.

Sir, Madam

If your son likes

I like him

I am a little beautiful

But not fair in complexion

No wealth

Other than my education.

I could call on, on any day

To see your son

May you have

The blessings of the Triple Gem.

Once again, though the poet examines an issue relating to the

marriage in our society, the main issues here is that his inability to

represent this experience using a poetic language, hence it becomes a

mere report of an important experience.

Putting up faces is a common feature in our society. In attending a

funeral, not only close relatives but also their friends put up sad

faces to suit the occasion. The poem ‘Miturage viyapath piyage maranaya’

(The death of a friend’s aged father) portrays such an experience. It

seems that objectives of the three friends who are known as trinity,

visit an ex-girl friend on the pretext of visiting the funeral of the

friend’s father.

The death of a friend’s old father

Three friends known as the trinity

Went to see

The remains of the

friend’s old father

To share their grief

Suppressing smiles, jokes

They paid their last respects

With folded palms

Thus fulfilling their duty

The friend inquires

A cup of tea

Cold drink

Or

A bit of food

No thanks

There is another funeral

We will have to have meals there

No need to repent

He lived a long life

I did my duty

Father lived happily

Now, the main task is over

Nearby, lives my female friend

Though I forget her

I remind her sometimes

like lightning in the heart

Two of you encourage me

To call on her

Without ringing the bell

She came well-dressed

In accordance with

Age, education and disposition

She is pleasant

The beauty of the past

Has not vanished

Smiles as before

She introduced the trio to husband

Couldn’t she forget her senior university teacher?

She calls three teachers

By old names

…..

My husband gave me

Two gems

Then, how are you?

Would you like to have

A glass of whisky

A glass of Brandy

Or a little bit of red wine?

Three crystal glasses are

Evenly filled

She offers drinks kneeling down

…..

What do you like to have

To mix with?

Soda only

High blood pressure

Blood sugar

Cholesterol

Problems in the liver

….

Her gait

Smile

Disposition

Remain unchanged

With a little deeper voice

That is not the issue

For me

She called me as well

As she addressed my friends

By old names

Offered drinks kneeling down

Kissed their cheeks as mine

Could this be possible?

The girl in love with me

for three years

Dissolved in the glass her image

As an ice cube

Beautiful figure, smiles

Chatting

All have divided among

The three

Could it ever happen?

The poem commences with a visiting to a funeral of a friend’s father

who had died having lived a long life. The trio who are now senior

university professors put up false appearances at the funeral in order

to please the friend, and to visit an ex-girl friend of one of them. The

ex-girlfriend, now a middle aged woman, is married and has two children.

She treats them well offering liquor. The narrator could not quite

comprehend as how she, who had been his girlfriend for three years,

could treat the trio equally without any special preference to him.

Exploring nostalgia

The poet here also explores the theme of nostalgia. It is obvious

that the narrator tries to revisit the past by calling on his

ex-girlfriend. Once again, time has changed everything; both the

ex-girlfriend and the narrator. The poet has used a potent metaphor of

dissolving ice cube in a crystal glass to the image of his

ex-girlfriend, but once again, in its totality, this rich experience has

becomes a mere narrative poem with little poetic diction.

The title poem of the collection Lokaya Miyayai (The world dies) also

deals with time and its overarching impact at present. In essence, the

poem codifies a story of a generation and a world which is dissipating

leaving physical monuments of a bygone era to crumble. The poet brings

out the changes through decaying of an old house.

The world dies …

…..

From the holes in the wall

Rats peep out

Wait a while

Then run here and there

In the noon

In search of delicacies

Mingled with the

gathering darkness

The ancient musty odour

emanates from the house

The paintings on soaked walls

The telephone does not ring

But make a jara bara noise.

From a series of black

and white photographs

hung on here and there

the members of the Vasana family

look at all directions

No smile on a face

Now they are abroad

…..

Happily or sadly.

In the poem, ‘Makeeyamata Kalayai’ (The time to exit), the poet

narrates a daily routine of a senior bureaucrat in Sri Lanka. His day is

filled up with a series of meetings and the rest of the day, he goes on

shopping. His day commences with the sound of boiling water in the

kettle and ends with answering a call from the Minister. In my view, the

narrator of this long poem has some resemblance to James Joyce’s novel,

Ulysses in which the protagonist Leopold Bloom is the fictional hero.

In this poem, the poet uses both blank verse and conventional

rhythmic verse which has worked most of the time except when the rhyme

is flawed. The poet narrates a gamut of events that makes his day as

described by a gorgeous female television newscaster with a beaming

smile.

A mortar attacks in Mannar

Four died

The demonstration at the

Lipton Circuit

Attacked by the goons

Tear gas

Female suicide bombers head

On the roof

Doctors went on a strike

Patients suffer

…….

Voluntary teachers on a

hunger strike

More details after an interval

Smile appeared and disappeared

Smile fades away.

The harsh realities of the ordinary citizens is vividly realised in

the poem ‘Nidahasa Samaramu’ (Let’s celebrate the Independence). It is a

contrasting situation in the midst of the independent day and associated

pageantry of celebrations. But according to the poet, the poor in the

city had to wait until the barriers are opened to go on their routines

and buy daily provisions.

Let us celebrate the Independence

The independence

gained sixty years ago

Celebrated today

At the Independence Palace

Ministers

Top brass of the army

Fat wives

With propped up hair

Wearing sun-glasses

Red-coloured lips

Waving fans in their hands

Celebrate Independence

The nobles

Observed

One minute of silence

Getting up from their seats

To pay their respect

To the fallen soldiers

A lot of children

watch and celebrate

The independence

gained sixty years ago on television

March past

…

Could not go out

Should stay at home

Until

The Ministers

The officials

With armed convoys

Arrive home

Waiting the poor

To buy

A coconut

A little bit of rice

Some green leaf

Vegetable

Till the road

Open for traffic.

In the poem Nidahasa (Independence), the poet questions the very

notion of ‘Independence’ providing a private perspective through a

series of questions he holds dearly in his heart.

Nidahasa (Independence)

Where is the Independence

In a flag

In books

On the road

In a rain forest

Near the sun

Near the moon

In the wind

On top of the trees

In the sea

In a foam on a wave

In a river

In a tributary

In the tank

On the lap of a woman

In the crown of a king

Under a bo tree

In the courtyard of a bo tree

In a Buddhist temple

In a church

In a Kovil

In the next world

Or in this world

In the poem ‘Jeevitaya’ (The life), the poet compares life to a wet

bird hopping from one branch to another. In essence, what the poet says

is that life is a daily struggle for survival.

A rich harvest of life experiences

This collection offers a rich harvest of life experiences of an

individual who has experienced a vivid public life in its multitudes.

Evidently, the subject matter that goes into the poetry is derived from

the day-to-day life as well as from the life experiences of the poet.

Though the mixing of blank verse and traditional verse clashes on

occasion, it in a way facilitates the emergence of a variety of moods

within the matrix of a single poem. This is particularly manifested in

poems such as ‘Makeeyamata Kalayaye’ (The time to exit).

At times sheer length of the poems makes the reader boring, rendering

such poems meaningless though the experience that goes into such poems

is rich.

However, the major deficiency is the poet’s inability to develop an

appropriate poetic diction to convey his musings. Some imagery such as

dilapidated houses is recurrent throughout the collection.

The collection of poetry ‘Lokaya Miyayai’ is noted for its rich

imagination and public and private thoughts on the world around a mature

individual. Some of the poems would have been more effective if the

author had condensed them into half of their original lengths and focus

on compiling a language rich with metaphors and images.

The poems indeed codify a new milieu and a world that the poet

inhabited in his diverse capacities. I wondered more than once had he

converted these diverse themes and his experiences into long or short

prose, they would undoubtedly enrich the Sinhala prose literature.

I sincerely hope that despite the strengths and weaknesses, Lokaya

Miyayai will open up a rich and meaningful dialogue focusing on the

future of Sinhalese poetry in the new millennium.

|