|

Leo Tolstoy’s KREUTZER SONATA-:

The resonance of paranoia

by Dr Siri GALHENAGE

Last November, many events took place around the world to celebrate

the life and work of Leo Tolstoy, also known as Count Lev Nikolayevich

Tolstoy. Writing about this important event, the Moscow correspondent of

Daily Telegraph Andrew Osborn said that “Russia now is being accused of

abandoning its literary past in case of the outstanding Russian writer

Leo Tolstoy, because Russia ignores the 100-year anniversary of his

death.”

This is a clear indication how literary works of even literary giants

are treated and interpreted over the years. Could universal judgements

be passed on the work of writers such as Tolstoy and Pasternak is a key

question which merits our attention.

However,

interpretations, and analysis of Tolstoy’s work, giving new insights

into the work of this literary genius will take place from different

cities of the world by different critics. However,

interpretations, and analysis of Tolstoy’s work, giving new insights

into the work of this literary genius will take place from different

cities of the world by different critics.

The following is an exclusive analysis of Leo Tolstoy's much

discussed novella--Kreutzer Sonata-- by Dr Siri Galhenage who has worked

in the UK and Australia as a Consultant Psychiatrist.

Pozdnychev’s heightened suspicion and jealousy

Tolstoy has established craftily that the marital relationship

between Pozdnychev and his wife is not functioning as it should be

between a normal husband and wife.

In this toxic arena enters a musician, by the name of Trukhachevski –

a semi-professional violinist who is described as ‘not bad looking’ with

superficial ‘gaiety’ and ‘maintaining his dignity in externals’,

Pozdnychev soon to undervalue him as a ‘worthless man’. But he appeals

to his wife as she was looking for a musician to accompany her on the

violin.

Trukhachevski’s talent for music; the nearness that came of playing

together; the impressionable nature of music, especially of the violin;

and his apparent lustful gaze towards his wife, tormented Pozdnychev and

creates suspicion and jealousy. He begins to suspect that the sound of

the piano was purposely made to drown the sound of their voices and

probably their kisses, as they practised.

The tension between the couple came to a head when she approached him

to express her displeasure regarding his behaviour towards her. He was

full of rage. ‘Having given reins to my rage, I revelled in it and

wished to do something still more unusual to show the extreme degree of

my anger. I felt a terrible desire to beat her, to kill her’.

‘I value not you [devil take you] but the honour of the family’, he

said to her. He confesses that he is jealous of Trukhachevski. ‘Could a

decent woman have any other feeling for such a man than the pleasure of

his music?’ she replies. Although he thought that she was covering up,

they made peace ‘under the influence of the feeling that was called

love’.

Despite all these, preparations continued for a musical performance

by the duet, followed by dinner to be held the following weekend at

their mansion.The musical evening proceeded without incident, except

that before the music began Pozdnychev followed the duet’s movements and

looks. They played Beethoven’s ‘Kreutzer Sonata’, which he revealed had

an ‘awful effect’ on him, making him ‘agitated’.

‘It was as if quite new feelings, new possibilities, of which I had

‘till then been unaware, had been revealed to me’. As he left that

evening, Trukhachevski said that he hoped to repeat the pleasure when he

next came to Moscow.

Pozdnychev goes away on official business and on the second day he

receives a letter from his wife. In addition to household matters she

mentions that Trukhachevski had called in to deliver some music ‘as

promised’.

He was unpleasantly struck by the news that the violinist had stayed

on in Moscow and had arranged to visit his wife in his absence. ‘The mad

beast of jealousy began to growl in its kennel and wanted to leap out,

but I was afraid of that beast and quickly fastened him’.

Pozdnychev was tormented by intrusive thoughts and counter- thoughts

regarding the suspected unfaithfulness of his wife. At this stage, it is

pure Imagination of what may have gone on between his wife and the

violinist in his absence but the very thought process inflames his

jealousy, and ‘burnt him with indignation’.

‘The vividness with which they presented themselves seemed to serve

as proof that what I imagined was real’. The humiliation he felt as a

result of Trukhachevski’s apparent victory over him fills him with a

strong feeling of hatred towards his wife.

He even suspected the paternity of his children: ‘perhaps she long

ago carried on with the footman, and so got the children who are

considered mine!’ He claimed to have complete ownership to her body, yet

felt that he had no control over it.

He predicted that some dreadful event is about to happen. A strange

sense of joy arises in him that his torture would be over, that now he

could punish her, and could get rid of her.

Pozdnychev

decides to cut short his official business and returns home. The first

thing he noticed on entering the house, past mid- night, is a man’s

cloak hanging on a stand: ‘I ought to have been surprised but was not,

for I had expected it’. Pozdnychev

decides to cut short his official business and returns home. The first

thing he noticed on entering the house, past mid- night, is a man’s

cloak hanging on a stand: ‘I ought to have been surprised but was not,

for I had expected it’.

What he imagined has now become a reality. He picks up a dagger and

entered the room where his wife and the violinist were having a union

outside their marriage. The expression of terror in them gave him a

sense of perverse pleasure.

He also detected signs of annoyance in his wife’s face for what he

thought was the disruption to her ‘love’s raptures’. He stabs her on the

side below the ribs with all his might. As she lay dying, what was

important to him was her confession of unfaithfulness, which he did not

receive; he felt that it was beneath her to admit her guilt.

The assailant admitted that he was aware of his action with

extraordinary clearness. ‘I knew what I was doing when I did it’. ‘I was

doing an awful thing such as I had never done before, which would have

terrible consequences’. He said that jealousy was not the only reason

for his act of murder.

The court decided that he was a wronged husband who killed his wife

defending his outraged honour! He was acquitted!! So he lived to tell

his tale.

Pozdnychev’s background

Pozdnychev was born into the nineteenth century Russian upper class

of land owners. He was brought up in a social milieu where men

determined the ‘moral code’ and women submissively adapted to it, both

sexes engaging in debauchery, overtly when single and covertly during

marriage. In cases of alleged wrong-doing, the judicial system was

designed to protect men. It was a breeding ground for jealousy,

suspicion and acrimony.

Pozdnyshev was a landowner, a graduate of the university and a

marshal of the gentry.

He grew up in a society that expected men, in their formative years,

to engage in sexual activity without making any moral commitment to

women with whom men need not develop any attachments.

Such behaviour was considered legitimate, ‘good for health’,

‘something to be proud of’, often sanctioned by parents and even by the

State that regulated brothels to make them safe for boys.

Pozdnyshev indulged in debauchery since the age of 16 but suffered a

deep sense of remorse for having ‘lost his innocence’ thinking that he

has sullied his ability for intimacy with women. He could detect a

debauchee by the way the latter eyed a woman.

In defiance of such a sordid and hypocritical background, and through

his own experience, Pozdnychev seemed to have developed a certain value

system, albeit idiosyncratic, overvalued and even malignant.

He believed that a woman’s charm could be deceptive; love - a

pretence; sex - brutish; matrimonial sacrament - a mere ritual without

spiritual grace; marriage - acrimonious; pregnancy – a protection

against feminine coquetry; and child rearing – a torment.

He demanded his wife’s loyalty, her commitment and the exclusivity of

her intimacy, without directly raising issues of sexual fidelity.

It was the alleged transgression of his self imposed code of conduct

which led to his wife receiving her ultimate punishment.

But there was an even more virulent psychological aspect hidden

beneath the above socio-cultural and moral influences -- a paranoid

process presenting in the form of morbid jealousy.

Pozdnychev married a girl of ‘moral perfection’, and his expectation

was that she would maintain her morality despite living in ‘a mire of

coquetry’.

But with ongoing marital discord, her increased attention to her

appearance [free from pregnancy] and her revival in interest in the

piano, shoots of suspicion started to spring up in his mind.

The situation came to a head when a third party entered the intimacy

of their relationship – a violinist who formed a duet with his wife.

Pozdnychev felt threatened by his perceived rival. He compensated for

the threat to his self-esteem by either denigrating him or actively

encouraging their music [reaction formation].

He was tormented by thoughts of disloyalty, betrayal and of desertion

by his wife and became resentful of the imminent loss of his

‘possession’. He viewed with suspicion the proximity of the violinist to

the pianist and their apparent amorous gaze, and feared the ‘hypnotising

effect’ of music on each other. He thought that the music was purposely

made to dampen their chatter and their kisses.

The Kreutzer sonata they played together had a negative impact on his

body and mind. Recurrent and vivid imaginings of his wife’s

unfaithfulness, in his absence, inflamed his jealousy and led him to

believe that they were real.

Faithfulness and loyalty

Faithfulness and loyalty in action alone was never enough for the

jealous, it had to be in thought as well.

As such doubt became a constant companion that stirred up his

jealousy. Pozdnychev even began to doubt the paternity of his children

entertaining transient thoughts that his footman could be their father.

Alongside feelings of humiliation resulting from the perceived

preference of the rival by his wife was the insatiable need to expose

her unfaithfulness and to deliver punishment.

A central issue in morbid [paranoid] jealousy is a perverse sense of

ownership – ‘either I own her or destroy her’. Pozdnychev discovered

what he thought was proof of his wife’s unfaithfulness and he destroyed

her. No evidence of innocence or confession was going to satisfy him.

Conclusion

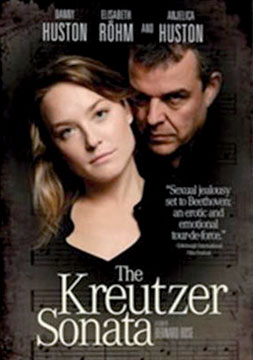

Undoubtedly, Kreutzer Sonata is one of the major literary works by

Tolstoy, which deals with the perennial issues of morality, love and

sexual abstinence.

It is important to recognise that the story is narrated through the

perspective of the main protagonist, Pozdnyshev.

According to some critics, the novella presents Tolstoy's

controversial view on sexuality, which affirms that physical craving is

an impediment to relations between men and women and may result in

calamity.

According to the respected German psychiatrist, Ernst Kretschmer

[1927], paranoia derives from cumulative influences of a noxious social

environment, a characteristic personality with marked ‘sensitivity’ and

a personal experience ‘meaningful’ to the individual.

In capturing all the above features of this morbid human condition in

Kreutzer Sonata, Leo Tolstoy, acknowledged by many as the greatest

writer of the 19th century, appears to me to be one step ahead of the

psychiatric profession!

For reader’s feedback: [email protected]

|