Rags to riches picaresque

Reviewed by Ian Mc Gillis

|

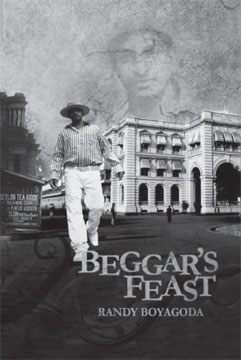

Beggar’s Feast

Authour : Randy Boyagoda

Perera-Hussein

|

A picaresque hero, the Oxford Learner's Dictionary tells us, is "a

person who is sometimes dishonest, but easy to like." For future

editions, the folks at Oxford might want to consider citing the hero of

Randy Boyagoda's picaresque second novel as Exhibit A - though it must

be said that Sam Kandy does stretch the "sometimes" and "easy" parts of

that definition as far as they'll go without snapping.

Rags-to-riches narratives seldom have much humbler starting points

than the Ceylon village where Beggar's Feast's protagonist is born in

1899. Warned by the local astrologist that their son's horoscope

portends family disaster, his parents shunt him off to a Buddhist

monastery on his 10th birthday.

But this boy has a very different life in mind for himself. Quickly

giving the monks the slip, Sam (the name he gives himself on

reinvention) soon finds himself hustling on the streets of Colombo.

Pursuing his life's mission to return victorious to his home village, he

proceeds, via a tortuous route, to a self-willed transition from a "no

one from nowhere" to shipping magnate and man of substance.

Sam's life

Beggar's Feast spans the hundred years of Sam's life. Many writers

taking on an equivalent historical sweep would probably have filled a

novel twice this one's length, but Boyagoda, the Oshawa-born son of Sri

Lankan immigrants, has a flair for concision. Decades of history and

politics are represented with the deftest of sketches, as with the

observation of how "one morning in 1972 (the name) Ceylon was decreed

banished from the island, only to be found alive and thriving in London

and Dubai, Scarborough and Brampton, where it became the watchword of

conjuring emigrants ignored by their television children."

Boyagoda's central creation might be dismissible as simply a handy

symbol for Sri Lanka's fitful century-long progress from backwater

colony to internally divided modern state, except that Sam is very much

his own man. He won't be contained.

Boyagoda is certainly unconcerned with any conventional notion of

character sympathy: Sam exhibits a streak of cruelty that can be only

partially explained away by his childhood humiliation and his broader

status as an exploited subject of colonialism.

He mistreats people because he can. Spouses are cynically acquired,

callously abandoned and, in one case, killed; children are alternately

lavished and ignored.

Soul

You might say Sam gains the world and loses his soul except that the

circumstances of his life make the very concept of soul seem like a

bourgeois indulgence. And yet, against all better judgment, the reader

warms to him and his single-minded drive to transcend his origins. He's

Naipaul's Mr Biswas as unapologetic success rather than embittered

failure, Richler's Duddy Kravitz followed far past his apprenticeship.

If you've found a place in your heart for either of those complicated

figures, make way for Sam Kandy and meet Randy Boyagoda at the 2012

Galle Literary Festival. |