|

Lab-grown egg cells could

revolutionise fertility and even banish menopause :

Scientists rewrite rules of human reproduction

by Steve CONNOR

The first human egg cells that have been grown entirely in the

laboratory from stem cells could be fertilised later this year in a

development that will revolutionise fertility treatment and might even

lead to a reversal of the menopause in older women. Scientists are about

to request a licence from the UK fertility watchdog to fertilise the

eggs as part of a series of tests to generate an unlimited supply of

human eggs, a breakthrough that could help infertile women to have

babies as well as making women as fertile in later life as men.

Producing human eggs from stem cells would also open up the

possibility of replenishing the ovaries of older women so that they do

not suffer the age-related health problems associated with the

menopause, from osteoporosis to heart disease. Producing human eggs from stem cells would also open up the

possibility of replenishing the ovaries of older women so that they do

not suffer the age-related health problems associated with the

menopause, from osteoporosis to heart disease.

Some scientists are even suggesting the possibility of producing an

“elixir of youth” for women, where the menopause is eradicated and older

women will retain the health they enjoyed when younger.

Researchers at Edinburgh University are working with a team from

Harvard Medical School in Boston to be the first in the world to produce

mature human eggs from stem cells isolated from human ovarian tissue.

Until now, it has only been possible to isolate a relatively small

number of mature human egg cells directly from the ovaries of women who

have been stimulated with hormones. This technical limitation has led to

an acute shortage of human eggs, or “oocycts”, for IVF treatment as well

as scientific research.

The scientists want to fertilise the laboratory-grown egg cells with

human sperm to prove that they are viable. Any resulting embryos will be

studied for up to 14 days - the legal limit - to see if they are normal.

These early embryos will not be transplanted into a woman's womb

because they will be deemed experimental material, but will either be

frozen or allowed to perish.

Evelyn Telfer, a reproductive biologist at Edinburgh University, has

already informally approached the Human Fertilisation and Embryology

Authority (HFEA) with a view to submitting a formal licence application

within the next few weeks.

“We hope to apply for a research licence to do the fertilisation of

the in vitro grown oocytes within the IVF unit at the Edinburgh Royal

Infirmary,” Dr Telfer said.

“Could the fertilisation take place this year? Yes, absolutely,” she

said. Professor Richard Anderson of the MRC Centre for Reproductive

Health, who will be in charge of the clinical aspects of the work, said:

“The aim will be to demonstrate that the eggs that we’ve generated in

vitro are competent to form embryos and that’s the best test that an egg

is an egg,”

Generating an unlimited supply of human eggs and the prospect of

reversing the menopause was made possible by a series of breakthroughs

led by Professor Jonathan Tilly of Harvard.

In 2004, he astounded the world of reproductive biology by suggesting

that there were active stem cells in the ovaries of mice that seemed

capable of replenishing eggs throughout life.

For half a century, a dogma of reproductive biology was that women

are born with their full complement of egg cells which they gradually

lose through life until they run out when they reach the menopause.

“This age-old belief that females are given a fixed ‘bank account’ of

eggs at birth is incorrect,” Professor Tilly said.

“In fact ovaries in adulthood are probably more closely matched to

testes in adulthood in their capacity to make new germ cells, which are

the special cells that give rise to sperm and eggs,“ he said.

”Over the past 50 years, all the basic science, all the clinical work

and all the clinical outcome was predicated on one simple belief, that

is the oocyte pool, the early egg-cell pool in the ovaries was a fixed

entity, and once those eggs were used up they cannot be renewed,

replenished or replaced,“ he added.

Last month, Prof Tilly published pioneering research showing that

these stem cells exist in human ovaries and that they could be

stimulated in the laboratory to grow into immature egg cells.

He is collaborating with Dr Telfer, who was once sceptical of his

research, because in Edinburgh she has pioneered a technique for growing

immature eggs cells to the fully “ripened” stage when they can be

fertilised.

”It's been fun to work with her because she's been one of the most

vocal critics of this work years ago and it's great that she's come

about and changed her views,“ Prof Tilly said.

”I think personally [fertilising the first eggs] is do-able. I see no

hurdles why it cannot be done this year,“ he said.

Dr Telfer added: “The important thing is that if you can show you can

get ovarian stem cells from human ovary you then have the potential to

do more for fertility preservation.

“We have all the local ethical approval in place and we’re now

looking at the process of the HFEA application. There is a push for us

to do it now,” she added.

The Independent

The mystery of human consciousness

A wakening from anesthesia is often associated with an initial phase

of delirious struggle before the full restoration of awareness and

orientation to one's surroundings. Scientists now know why this may

occur: primitive consciousness emerges first. Using brain imaging

techniques in healthy volunteers, a team of scientists led by Adjunct

Prof Harry Scheinin, M.D. from the University of Turku, Turku, Finland

in collaboration with investigators from the University of California,

Irvine, USA, have now imaged the process of returning consciousness

after general anesthesia. The emergence of consciousness was found to be

associated with activations of deep, primitive brain structures rather

than the evolutionary younger neocortex.

These results may represent an important step forward in the

scientific explanation of human consciousness. The study was part of the

Research Program on Neuroscience by the Academy of Finland. “We expected

to see the outer bits of brain, the cerebral cortex (often thought to be

the seat of higher human consciousness), would turn back on when

consciousness was restored following anesthesia. Surprisingly, that is

not what the images showed us. In fact, the central core structures of

the more primitive brain structures including the thalamus and parts of

the limbic system appeared to become functional first, suggesting that a

foundational primitive conscious state must be restored before higher

order conscious activity can occur” Scheinin said. These results may represent an important step forward in the

scientific explanation of human consciousness. The study was part of the

Research Program on Neuroscience by the Academy of Finland. “We expected

to see the outer bits of brain, the cerebral cortex (often thought to be

the seat of higher human consciousness), would turn back on when

consciousness was restored following anesthesia. Surprisingly, that is

not what the images showed us. In fact, the central core structures of

the more primitive brain structures including the thalamus and parts of

the limbic system appeared to become functional first, suggesting that a

foundational primitive conscious state must be restored before higher

order conscious activity can occur” Scheinin said.

Twenty young healthy volunteers were put under anesthesia in a brain

scanner using either dexme-detomidine or propofol anesthetic drugs. The

subjects were then woken up while brain activity pictures were being

taken. Dexmedetomidine is used as a sedative in the intensive care unit

setting and propofol is widely used for induction and maintenance of

general anesthesia.

Dexmedetomidineinduced unconsciousness has a close resemblance to

normal physiological sleep, as it can be reversed with mild physical

stimulation or loud voices without requiring any change in the dosing of

the drug. This unique property was critical to the study design, as it

enabled the investigators to separate the brain activity changes

associated with the changing level of consciousness from the drugrelated

effects on the brain. The staterelated changes in brain activity were

imaged with positron emission tomography (PET).

The emergence of consciousness, as assessed with a motor response to

a spoken command, was associated with the activation of a core network

involving subcortical and limbic regions that became functionally

coupled with parts of frontal and inferior parietal cortices upon

awakening from dexme-detomidine-induced unconsciousness. This network

thus enabled the subjective awareness of the external world and the

capacity to behaviorally express the contents of consciousness through

voluntary responses.

Interestingly, the same deep brain structures, i.e. the brain stem,

thalamus, hypothalamus and the anterior cingulate cortex, were activated

also upon emergence from propofol anesthesia, suggesting a common,

drugindependent mechanism of arousal. For both drugs, activations seen

upon regaining consciousness were thus mostly localized in deep,

phylogenetically old brain structures rather than in the neocortex. The

researchers speculate that because current depth-of-anesthesia

monitoring technology is based on cortical electroencephalography (EEG)

measurement (i.e., measuring electrical signals on the sur-face of the

scalp that arise from the brain's cortical surface), their results help

to explain why these devices fail in differentiating the conscious and

unconscious states and why patient awareness during general anesthesia

may not always be detected. The results presented here also add to the

current understanding of anesthesia mechanisms and form the foundation

for developing more reliable depth-of-anesthesia technology.

The anesthetised brain provides new views into the emergence of

consciousness. Anesthetic agents are clinically useful for their

remarkable property of being able to manipulate the state of

consciousness. When given a sufficient dose of an anesthetic, a person

will lose the precious but mysterious capacity of being aware of one's

own self and the surrounding world, and will sink into a state of

oblivion. Conversely, when the dose is lightened or wears off, the brain

almost magically recreates a subjective sense of being as experience and

awareness returns. The ultimate nature of consciousness remains a

mystery, but anesthesia offers a unique window for imaging internal

brain activity when the subjective phenomenon of consciousness first

vanishes and then re-emerges. This study was designed to give the

clearest picture so far of the internal brain processes involved in this

phenomenon.

The results may also have broader implications. The demonstration of

which brain mechanisms are involved in the emergence of the conscious

state is an important step forward in the scientific explanation of

consciousness. Yet, much harder questions remain. How and why do these

neural mechanisms create the subjective feeling of being, the awareness

of self and environment the state of being conscious?

NYT

A link between atherosclerosis and autoimmunity

Those who suffer from autoimmune diseases also display a tendency to

develop atherosclerosis - the condition popularly known as hardening of

the arteries. Clinical researchers at LMU, in collaboration with

colleagues in Würzburg, have now discovered a mechanism which helps to

explain the connection between the two types of disorder.

The link is provided by a specific class of immune cells called

plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs). pDCs respond to DNA released from

damaged and dying cells by secreting interferon proteins which stimulate

the immune reactions that underlie autoimmune diseases. The new study

shows that stimulation of pDCs by a specific DNA-protein complex

contributes to the progression of atherosclerosis. The link is provided by a specific class of immune cells called

plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs). pDCs respond to DNA released from

damaged and dying cells by secreting interferon proteins which stimulate

the immune reactions that underlie autoimmune diseases. The new study

shows that stimulation of pDCs by a specific DNA-protein complex

contributes to the progression of atherosclerosis.

Implications

The findings may have implications for new strategies for the

treatment of a whole spectrum of conditions that are associated with

chronic inflammatory reactions. Atherosclerosis is a major cause of

death in Western societies. The illness is due to the formation of

insoluble deposits called atherosclerotic plaques on the walls of major

arteries as a consequence of chronic, localised inflammation reactions.

By reducing blood flow, the plaques can provoke heart attacks and

strokes. A class of immune cells called dendritic cells plays a crucial

role in facilitating the development of these plaques. The term refers

to a heterogeneous cell population that makes up part of the immune

system. Among the cell types represented in this population are the

so-called plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC), but their potential

significance for atherosclerosis had not been explored until now.

Disorders

A group of researchers led by Dr. Yvonne Döring in Prof Christian

Weber's department at LMU, together with a team supervised by

Privatdozentin Dr. Alma Zernecke of Würzburg University, has now shown

how pDCs promote the development of atherosclerosis – and explained why

patients with autoimmune disorders, such as psoriasis or systemic lupus

(SLE), show a predisposition to atherosclerosis.

Using laboratory mice as an experimental model, the researchers were

able to show that pDCs contribute to early steps in the formation of

athersclerotic lesions in the blood vessels. Stimulation of pDCs causes

them to secrete large amounts of interferons, proteins that strongly

stimulate inflammatory processes. The protein that induces the release

of interferons is produced by immune cells that accumulate specifically

at sites of inflammation, and mice that are unable to produce this

protein also have fewer plaques. Stimulation of pDCs in turn leads to an

increase in the numbers of macrophages present in plaques. Macrophages

normally act as a clean-up crew, removing cell debris and fatty deposits

by ingesting and degrading them.

However, they can also “overindulge”, taking up more fat than they

can digest. When this happens, they turn into so-called foam cells that

promote rather than combat atherosclerosis. In addition, activated,

mature pDCs can initiate an immune response against certain molecules

found in atherosclerotic lesions, which further exacerbates the whole

process.

Disorders

The disorders of pDCs provides the link between atherosclerosis and

autoimmune diseases. “The pDCs themselves are stimulated by the

self-antigens that set off the autoimmune reactions which result in

conditions like psoriasis and SLE,” says Döring. Indeed, it is well

known that the secretion of interferons by activated pDCs contributes to

the genesis of a number of autoimmune diseases

“The findings also suggest new approaches to the treatment of chronic

inflammation that could be useful for a whole range of diseases,” said

Webber.

MNT

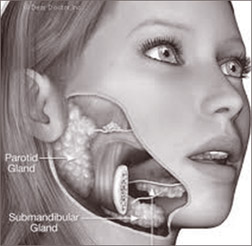

Enzyme in saliva helps regulate blood glucose

Scientists from the Monell Center report that blood glucose levels

following starch ingestion are influenced by genetically determined

differences in salivary amylase, an enzyme that breaks down dietary

starches. Specifically, higher salivary amylase activity is related to

lower blood glucose.

The findings are the first to demonstrate a significant metabolic

role for salivary amylase in starch digestion, suggesting that this oral

enzyme may contribute significantly to overall metabolic status. Other

implications relate to calculating the glycemic index of starch-rich

foods and ultimately the risk of developing diabetes “Two individuals

may have very different glycemic responses to the same starchy food,

depending on their amylase levels,” said lead author Abigail Mandel,

Ph.D., a nutritional scientist at Monell.

“Those with high amylase levels are better adapted to eat starches,

as they rapidly digest the starch while maintaining balanced blood

glucose levels. The opposite is true for those with low amylase levels. “Those with high amylase levels are better adapted to eat starches,

as they rapidly digest the starch while maintaining balanced blood

glucose levels. The opposite is true for those with low amylase levels.

As such, people may want to take their amylase levels into account if

they are paying attention to the glycemic index of the foods they are

eating.” Starch from wheat, potatoes, corn, rice, and other grains is a

major component of the United States diet, comprising up to 60 percent

of our calories. Amylase enzymes secreted in saliva help break down

starches into simpler sugar molecules that can be absorbed into the

bloodstream. In this way, amylase activity influences blood glucose

levels, which need to be maintained within an optimal range for good

health.

Starch

A previous study had demonstrated that individuals with high salivary

amylase activity are able to break down oral starch very rapidly. This

finding led the researchers to ask how this ‘pre-digestion’ contributes

to overall starch digestion and glucose metabolism.

In the current study, published online in *The Journal of Nutrition*,

amylase activity was measured in saliva samples obtained from 48 healthy

adults. Based on extremes of salivary amylase activity, two groups of

seven were formed: high amylase (HA) and low amylase (LA). Each subject

drank a simplified corn starch solution and blood samples were obtained

over a two hour period afterwards. The samples were analysed to

determine blood glucose levels and insulin concentrations.

After ingesting the starch, individuals in the HA group had lower

blood glucose levels relative to those in the LA group. This appears to

be related to an early release of insulin by the HA individuals.

“Not all people are the same in their ability to handle starch,” said

senior author Paul Breslin, Ph.D., a sensory geneticist at Monell.

“People with higher levels of salivary amylase are able to maintain

more stable blood glucose levels when consuming starch.

This might ultimately lessen their risk for insulin resistance and

non-insulin dependent diabetes.”

Additional studies will confirm the current findings using more

complex starchy foods, such as bread and pasta. Another focus will

involve identifying the neuroendocrine mechanisms that connect starch

breakdown in the mouth with insulin release.

- Medicalxpress

|