UN Human Rights Council – a butterfly or a caterpillar with

lipstick?

by Mohan Pieris

|

|

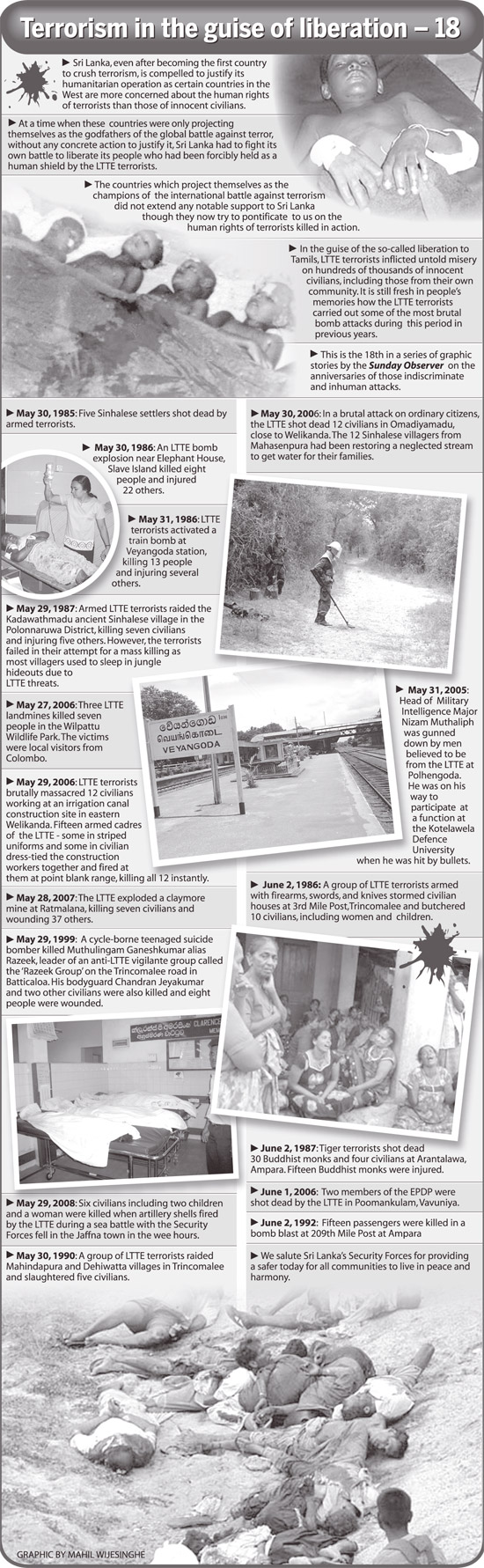

The suffering of civilians

fleeing the LTTE was ignored by most countries |

The ides of March have come and gone but the passage of the famous or

infamous US sponsored resolution on Sri Lanka continues to provoke

discussion and discourse not to mention the controversy it has raised

among us on its pros and cons.

I thought it opportune that I should share some thoughts with you on

the United Nations Human Rights Council as a body and tell you what I

feel is the legal impact of this resolution. That overview of the body –

the scope and extent of its powers – will put the resolution in its

correct perspective.

That will also strengthen my argument that the resolution finds not

place in the overarching scheme of the building blocks of the Council.

HR Commission (1948-2006)

|

Mohan Pieris |

The Human Rights Commission-the predecessor to the Human Rights

Council – was established in 1948 – the year we gained independence.

This Commission in fairness to it did some useful work. Immediately

after its formation, it focused its attention on drafting the major

human rights document of the world - the Universal Declaration of Human

Rights (UDHR). It was adopted as a General Assembly Resolution on 10

December 1948 – a day we celebrate every year as International Human

Rights Day. As a General Assembly Resolution we call it a soft law which

means a legally non binding document. But its uniqueness lay in its

trend setting standards such as right to freedom and equality and

freedom from discrimination. It was trend setting because most countries

adopt them in their constitutions. You would observe that they find

their place in our 1978 Constitution too.

This Commission brought forth some other standard setting

international contentions to which Sri Lanka became a party-such as the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the

International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ICESC)

and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). In fact our

National Action Plan on Human Rights has the goal of progressively

improving these covenant rights. So much for the good work of the

Commission. But there is a flip side to the Commission.

Anti-Third World bias

|

The UN Human Rights Council |

Towards the 1980s it was widely accepted that the Human Rights

Commission began to sport a Western and anti-Third World bias.

The Commission passed almost no country-specific resolution against

any Western Country, as all of its attention was focused on small Third

World countries that had the misfortune of being caught up in the

maelstrom of the formal end of the Cold War – countries such as Cambodia

or El-Salvador. Indeed, countries like these remained continuously on

the Commission’s agenda during the 1990s.

So the Third World Countries no longer looked at the UN Human Rights

Commission as a weapon of the weak but as a bludgeon. In fact the agenda

on the Commission was substantially influenced by the UN General

Assembly and there was a plethora – I would call an unreasonable number

of condemnatory resolutions against the Third World and it was this

politicization that drove countries to charter a so called reform that

would replace the Commission with a Council.

Did the Human Rights Commission fail?

In fact if you ask me the question – did the Human Rights Commission

fail, my answer would be – ask those who mattered and suffered – the

countries that were the subjects of resolutions constantly. Selectivity

and non objectivity – the two terms that we ever so often use today to

accuse the Human Rights Council were the pervasive norms in the

Commission and this was best captured by an English Professor of

International Law from Colin Warbick when he said – I quote “The

Commission lost its integrity and direction over time: with much of its

membership decisions, powers and focus coming to be fuelled by

disreputable goals rather than motivated by the aim of promoting,

protecting and advancing human rights.”

The legacy continues ...

Are these comments pertinent today to the work of the Human Rights

Council that replaced the Commission as a reformed body? I certainly

make the opinion that the comments that the Commission was biased and

partisan and disreputable goals were rife in targeting countries are

still relevant today and applicable to the Council in light of what we

went through on the 22nd of March.

Human Rights Council (2006)

In 2005 the then Secretary General of the UN Kofi Annan called for

the abolition of the Commission, and the establishment of an effective

Human Rights Council. Let me recall his words:

“We have now reached a point at which the Commission’s declining

credibility has cast a shadow on the reputation of the United Nations

system as a whole, and where piecemeal reforms will not be enough.”

Following a long process of negotiation the General assembly adopted

Resolution 60/251 on 15 March 2006 setting up the Human Rights Council.

You would be interested to note that the United States, Marshall Islands

and Palau voted against the resolution to establish the Council. Three

countries, Belarus, Iran and Venezuela abstained and 170 countries

including Sri Lanka voted for the resolution. The General Assembly

established the Council as a subsidiary organ. Thus the Commission was

abolished and the first Session of the Human Rights Council began in

Geneva in June 2006.

Membership

It is made up of 47 members, vis-a-vis the 53 members of the former

Commission. The membership is mandated on equitable geographical

distribution – members will be elected directly and individually by

secret ballot by the majority of the members of the General Assembly;

The General Assembly elected the first group of 47 members in May 2006

and Sri Lanka had the privilege of being a member in that first batch. It is made up of 47 members, vis-a-vis the 53 members of the former

Commission. The membership is mandated on equitable geographical

distribution – members will be elected directly and individually by

secret ballot by the majority of the members of the General Assembly;

The General Assembly elected the first group of 47 members in May 2006

and Sri Lanka had the privilege of being a member in that first batch.

The membership shall be based on equitable geographical distribution,

and seats shall be distributed as follows among regional groups:

Group of African States, thirteen;

Group of Asian States, thirteen;

Group of Eastern European States, six;

Group of Latin American and Caribbean States, eight; and

Group of Western European and other States, seven;

The members of the Council shall serve for a period of three years

and shall not be eligible for immediate re-election after two

consecutive terms.

There is a rider that the General Assembly lays down in para 8 of its

resolution for qualification to become a member-While electing the

members to the Council, the General Assembly must take into account “the

contribution of candidates to the promotion and protection of human

rights and their voluntary pledges and commitments made.”

One year later after the General Assembly resolution of 2006, in

2007, the Human Rights Council met in Geneva and adopted its

constitution which is called – the Institution Building Package 5/1 that

delineated the future work of the Council.

So we have two constitutional documents that must guide the work of

the Council and the Council cannot step outside of them-namely GA

resolution 60/251 of 2006 and the Council Resolution – Institution

Building Package of 2007.

To an international lawyer and even otherwise any thing done outside

the four corners of these two documents would be ultra vires-beyond the

powers of the Council.

The conduct of business in the Council has to be guided by the

parameters set by these two constructional documents. Even the moving

and passage of resolutions have to be authorized by the principles that

are found in these documents. Were they adhered to or even taken note

of?

I must tell you-if you look at the GA resolution of 2006, you will

see a pious declaration that was exhorted of the Human Rights

Council-the Council must be guided in its work by the principles of

“universality, impartiality and non-selectivity, constructive

international dialogue and co-operation.”

In other words the Council was expected to operate in a ‘transparent,

fair and impartial manner so as to achieve the objective of promoting

dialogue.

Quite contrary to these principles partiality and selectivity

characterized the ethos and undue haste with which certain countries

waged this war of attrition against Sri Lanka in the Council while

paradoxically the conduct of mighty nations in many a part of the world

passes muster. That conduct, however reprehensible it may be, is beyond

the pale of scrutiny of the Council.

This is why I say today that the Human Rights Council has been

drifting away from its obligation to keep up to its guiding principles.

No jurisdiction

If you analyse the Constitution of the Human Rights Council-the

Institution Building Package, nowhere would you find jurisdiction to go

into the recommendations of a domestic mechanism of a sovereign nation –

The LLRC was established by virtue of a legislation of the country

called the Commission of Inquiry Act. The findings of the Commission are

amenable to review by competent courts of this country but not by an

extra territorial body such as the Human Rights Council. The Institution

Building Package nowhere sets out powers to dissect and discuss the

recommendations of the Lessons Learnt Commission at the Human Rights

Council or for that matter even order an implementation of those

recommendations.

It is axiomatic that when the Human Rights Council voted on a

resolution to force a speedy implementation of the recommendation, the

council most respectfully took on a resolution without jurisdiction.

No country or any resolution of the Human Rights Council can set

deadlines when it comes to the matter of implementing recommendations of

the LLRC. That critical engagement about the contents of the LLRC Report

(especially those aspects pertaining to human rights and humanitarian

law) should, firstly, take place in a spirit of dialogue; and not by

attempting to introduce a resolution that binds a Government to some

international time-table, especially one set by a country which has no

moral right to extract commitments from other countries on human rights

protection.

The so called international community, as a critical legal scholar

stated, is a “completely impossible international player.” It reduces

small and weak States, in particular, to a state of helplessness in the

world; for, its hypocrisy, its arrogance, its “impossibility” cannot be

easily dealt with. This is the backdrop in which we faced the might of

the countries which sought to abuse their might.

The resolution was placed on the agenda regardless of many a salutary

positive in the Country. When we went to Geneva, we had a plethora of

positives.

At no point were we saying that we would resile from the

recommendations. The country had just implemented the substantial

portion of the interim recommendations of the LLRC.

Rehabilitation and reinsertion of former combatants was part of a

restorative justice program that was in place. The resettlement of the

displaced was a near success.

National Action Plan on Human Rights

Moreover, a national Action Plan on promotion and protection of Human

Rights was a reality which was the product of a deliberative process

which involved several stakeholders. In fact it was a fulfilment of a

voluntary pledge Sri Lanka made at a Universal Periodic Review that was

conducted in 2008. This Action Plan takes cognizance of what needs to be

done progressively on the human rights front. This stocktaking involved

an examination of Sri Lanka’s UPR, all of the Treaty Body

Recommendations, the recommendations of Special Rapporteurs, and Reports

of NGO’s submitted during the UPR. This process moved on to conduct

national consultations with the involvement of over 200 civil society

organizations as well as relevant governmental agencies to identify

issues in relation to 8 thematic areas. Eight Drafting Committees that

comprised six to ten experts from both Governmental and Non-Governmental

members were appointed to prepare a draft Action Plan in respect of each

thematic area. An important feature of the draft Action Plan is the

inclusion of measurable indicators, emphasizing a serious focus on the

monitoring and evaluation component.

In September 2010 under a Presidential directive, a Cabinet

sub-committee assisted by the Attorney-General was appointed to finalize

a composite plan incorporating the eight thematic plans.

The composite Plan titled the “National Action Plan for the

Protection and Promotion of Human Rights” and incorporating a time frame

for implementation, was approved by the cabinet and in all earnest the

implementation of the plan has commenced.

If I may itemize the 8 thematic areas of the Action Plan they are

Civil and Political Rights, Economic Social and Cultural Rights,

Prevention of Torture, Rights of Women, Labour Rights, Rights of Migrant

Workers, Rights of Children and Rights of Displaced Persons.

Each Thematic Action Plan divides into sub categories and effective

implementation of the plan has inspired a process that provides for the

input of all stakeholders including those who will assume responsibility

for implementation. The inclusion of measurable indicators will ensure

that there is a ready platform for Monitoring and Evaluation. We believe

that the Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E) component will make the

difference between a Plan that will work and one that may not.

Universal Periodic Review

I must make a mention of this process that has been built into both

the constitutional documents of the HRC. In fact the movers of the

resolution paid scant respect to this inbuilt mechanism of review,

The Institution Building Package of the Council tells us that a

country formally reports on its country situation at what is called

Universal Periodic Review. GA Resolution of 2006 mandated the HRC to

conduct this review. HRC Resolution of 2007 (Institution Building

Package) tells us that it is a co-operative mechanism based on an

interactive dialogue, with the full involvement of the country

concerned. All countries go through this and we went through this in

2008.

Our next cycle is later this year when we will lay bare our progress.

Though the Constitution of the Council stipulates this review process

and Sri Lanka contended that Universal Periodic Review would be the best

occasion for a review of Sri Lanka, this was not taken notice of in view

of the polarization and politicization that characterize the Human

Rights Council today.

I must say that we have reached a situation that anything and every

thing is cannon fodder for discussion in the name of human rights and

constitutional documents are consigned to history. That is why we say

that this resolution is non binding. It does not stand pari materia with

a security council resolution which usually amounts to an equivalent of

a court decree.

If you look at the text of the resolution, the permissive language in

which it is couched would indicate its non binding nature. The first

part calls upon the Government of Sri Lanka to implement the LLRC

recommendations.

The Second part requests the Government of Sri Lanka to present a

comprehensive action plan detailing the steps the Government has taken

and will take to implement the recommendations.

The third part encourages the office of the High Commissioner for

Human Rights to provide and the Government to accept any advice and

technical assistance that office would give us if we need such advice.

Despite all the developments I referred to earlier and the

government’s continuing commitment to charter a road map to implement

the LLRC recommendations sua sponte (on its own), certainly we did not

need a resolution that was placed on the agenda outside the parameters

of the Council’s jurisdiction.

This resolution was timed under a guise of co-operation to coerce and

force a country which was limping back to normalcy after so many years

of bloodshed and it was a stark reminder of the continuing legacy of

politicization of the Commission that haunts today its successor.

The Government has not rested on its laurels. The 258 recommendations

of the LLRC have been compartmentalized into 4 categories. There is a

road map that has been clearly strategized and we as Sri Lankans would

march towards that halcyon era when we will have eternal peace and

harmony.

But I venture to say this-when the human rights council was born, the

US Ambassador to the UN, John Bolton said with a flourish, “We want a

butterfly. We’re not going to put lipstick on a caterpillar and declare

it a success.”

In other words he wished the Council to be a butterfly and not

something where you put lipstick on a caterpillar-of course the

reference to a caterpillar was to the Commission. But in the light of

what has been the course of events at this council whose work suffers

from politicization, we wonder whether the General Assembly launched a

caterpillar with lipstick that has sullied the fabric of nations that

wish to rise from an internecine post conflict. So I part with these

thought-Universal Periodic Review would have been the best occasion for

a review. But a mistimed and ultra vires resolution once again tells us

a sad commentary-the trigger mechanisms for discussion in the Council

have grown higgledy-piggledy and those entrusted to watch over the

interests of human rights get it wrong as to the vires of their actions.

It reminds me of what that Roman poet Juvenal said in Latin – Quis

custodiet ipsos custodes? Who will guard the guardians? Who will take

custody of the custodians?

“Who indeed?”

The speech was made by Mohan Pieris, PC Senior Advisor to the Cabinet

on Legal Affairs, former Attorney - General and Chairman Seylan Bank at

a meeting organised by a leading service-oriented organisation in the

country. |