|

Opinion:

US wants speedy justice for ex-Tigers, but not for Guantanamo

detainees

by Daya GAMAGE

|

|

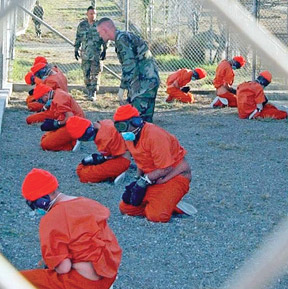

Guantanamo Bay prison |

The Asian Tribune US Bureau noted with amusement that the United

States reiterated that it looks forward to a ‘speedy and transparent

judicial process’ regarding ex-LTTE combatants and all other detainees

held in various prisons in Sri Lanka.

The US Embassy in Colombo made this remark on May 29, according to a

Sri Lankan national newspaper, in the wake of a campaign by some

political activists to secure the release of LTTE suspects and the

Government planning to set up three separate courts in Anuradhapura,

Vavuniya and Mannar to try them.

When the newspaper concerned asked about the matter, a spokesman for

the US Embassy had said that the US was only interested in the upholding

of the rule of law and quick judicial process with regard to LTTE

suspects, as recommended by the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation

Commission (LLRC).

The Sri Lanka media further reported that the Government has indicted

359 ex-combatants and are carrying out investigations regarding 309

others. Also, some other suspects arrested under the provisions of the

Prevention of Terrorism Act have been referred to various rehabilitation

centres.

Cabinet spokesman Minister Keheliya Rambukwella, reacting to the

United States request for a “speedy and transparent judicial process”

regarding ex-LTTE cadres said the Government had an action plan

regarding these cadres and was working in accordance with it.

“You have to remember that these are hardcore terrorists we are

talking about, who were taken into custody or who surrendered to the

Government. Therefore, legal proceedings are taking place against these

people. If some quarters are urging to speed up the process, what it

implies is that it’s asking the judicial process to be silent. This is

not within our system - our Constitution clearly provides for a coherent

legal system and this is what we are adhering to,” he said addressing

the media in Colombo.

Cabinet Minister Nimal Siripala de Silva told Parliament recently

that there were no political prisoners in Sri Lanka as made out by some

internal and external activists saying 359 former LTTE suspects are

being detained in the country’s prisons, of which 309 have cases pending

against them and added that three new High Courts would be established

to prosecute the cases.

|

| Water boarding |

|

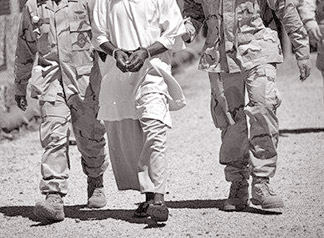

| A detainee in

Afghanistan |

What was amusing to this writer who covers the political scene in the

US and its connection to the Asian region and vice versa, is that due

process of law has been denied to ‘enemy combatants’ taken into US

custody, some incarcerated for as long as 10 years, preventing them from

obtaining legal advice, denying them the right to Habeas Corpus long

accepted since the promulgation of the Magna Carta in 1215, and often

subjected to brutal interrogation using ‘water boarding’ - a simulated

drowning technique categorised as a method of torture even by UN human

rights covenants.

Minister Rambukwella went onto point out that the request by certain

quarters completely ignored the procedures laid down. “There are

thousands of cases regarding ex-LTTE cadres and the Attorney General’s

Department has to follow these cases individually. I wonder whether what

they are asking is to bypass these procedures that have been laid down.

This request itself fundamentally and completely ignores the procedures

and the legality of these procedures”, he said.

The Asian Tribune, in this political note, will present the status of

‘long-term’ Guantanamo ‘enemy combatants’ and the cry from many

quarters, both legislative and civil society activists, to execute the

‘due process of law’ to either bring them to justice or release those

who have no culpability in international terrorism.

This political note however does not endeavour to deny a sovereign

State, be it the United States or Sri Lanka, the right to hold ‘enemy

combatants’ in incarceration until investigations, interrogations,

reports and other data are completed to execute the ‘due process of law’

to either bring them to justice or release them.

These nations have the right to protect themselves, eliminate

potential terrorist threats, safeguard their sovereignty and territorial

integrity.

Nevertheless, there is a stark difference between an eight to 10

years of incarceration without access to legal teams, alleged torture

such as water boarding, inhuman interrogation techniques that have been

exposed, denying Habeas Corpus while subverting the rule of law and

holding hardcore enemy combatants, apprehended or surrendered, for less

than three years for the purpose of completing investigations which help

a nation to either prevent potential threats and/or draw a comprehensive

strategy to eliminate a climate/atmosphere for the recurrence of such

non-international terrorism threatening the nation’s sovereignty and

territorial integrity.

|

Detainees at Guantanamo |

Here, we are talking about the eight to 10 year incarceration of

‘enemy combatants’ by the United States with scant regard for the rule

of law and due process of the law.

Military commissions

In 2001, President Bush issued an executive order authorising the

detention of non-citizen “enemy combatants.” In January 2002, the first

prisoners arrived at Guantanamo. Since then, the administration has

engaged in a systematic effort to deprive these detainees of even the

most basic legal rights, and strand them in permanent legal no-man’s

land. A series of Supreme Court cases, Rasul v. Bush, Hamdi v. Rumsfeld

and Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, undermined Bush’s strategy.

In late 2006, legal proceedings at Guantanamo came to a standstill,

because Congress passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006, under

intense pressure from the White House, following the Hamdan decision.

The Act essentially undermines the Habeas Corpus rights of the

detainees, allows the use of evidence obtained through torture, and does

not come close to satisfying fundamental due process requirements.

Wikileaks Guantánamo Bay files

In April 2011, Wikileaks released thousands of pages of classified

documents regarding the status of the almost 800 detainees, ranging from

ages 14 to 89, that have passed through or remain at the Guantanamo Bay

detention centre.

The US military dossiers, obtained by the New York Times and (London)

Guardian, reveal how many prisoners were flown to Guantánamo and held

captive for years on the flimsiest grounds or on the basis of lurid

confessions extracted by maltreatment.

Perhaps the most damning of these documents are the corroborative

evidence of the use of torture, the fact that more than 150 of the

detainees were innocent, and details on the seven men that have died

while in US custody. The files also contain detailed explanations of the

reasons used to justify the prisoners’ detention. In several cases, the

detainees were being held, not because they were dangerous, but because

they were believed to have useful information.

Vincent Warren, the Executive Director of the Centre for

Constitutional Rights, which represented clients in two Guantánamo

Supreme Court cases and coordinates the work of hundreds of pro bono

attorneys representing men detained at the prison camp in an op-ed piece

written January 9 this year said:

“From its inception, Guantánamo was intended to be a legal black

hole, designed to deny its prisoners the most basic human rights and due

process. Most of the 779 men who have been imprisoned and abused there

over the last 10 years were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

They were picked up far from any battlefield, turned over to the US

for a bounty, and held long after government officials acknowledged that

they were innocent of any wrongdoing. Likewise, the military commission

system created to try Guantánamo detainees was invented to allow

convictions based on evidence that would never be allowed in a

courtroom, including hearsay and evidence obtained through torture.”

Through years of tireless work in the courts, the Centre for

Constitutional Rights and pro bono attorneys across the US established

that Guantánamo prisoners have a right to counsel, a right to Habeas

Corpus and a right to meaningfully challenge their detention.

Though several Supreme Court rulings have confirmed that Guantánamo

does not exist outside the law, Congress has blocked attempts to close

the island internment camp at every turn. Provisions in the 2012

National Defence Authorization Act effectively prevent the release of 89

men who have been unanimously cleared by the CIA, FBI, NSC and

Department of Defense for transfer or resettlement, and codify a system

of indefinite detention.

Today, while 171 men remain imprisoned in Guantánamo without charge

or trial, fear-mongering and political gamesmanship have turned

Guantánamo into Obama’s forever prison. And, to date, more men have died

in Guantánamo than have been tried for the suspicions that landed them

there.

In a letter this January to US President Obama Kenneth Roth,

Executive Director, Human Rights Watch said:

“Your National Security Strategy explicitly recognises that the

United States’ “moral leadership is grounded principally in the power of

[its] example.” Your National Strategy for Counter terrorism recognises

the importance of adhering to US core values while fighting terrorism,

including through the respect for human rights.

“As the strategy eloquently outlined, “Where terrorists offer

injustice, disorder, and destruction, the United States must stand for

freedom, fairness, equality, dignity, hope, and opportunity. The power

and appeal of our values enables the United States to build a broad

coalition to act collectively against the common threat posed by

terrorists, further de-legitimising, isolating, and weakening our

adversaries.”

In his speech at Harvard Law School in September 2011,

counter-terrorism advisor John Brennan affirmed that the guiding

principle of all US action is to “uphold the core values that define us

as Americans, and that includes adhering to the rule of law.”

Human Rights Watch further reminds: “The example set by keeping

Guantanamo open undermines the US government’s long-standing opposition

to similar detention regimes in other countries. Over the years, the US

has opposed detention practices that are inconsistent with basic

principles of due process, openly criticising detentions without trial

by Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Malaysia and China. But such criticisms hold

little weight when the US adopts its own indefinite detention regime.”

The Guantanamo Detainee Review Task Force recommended 48 detainees

for continued detention without charge (now 46 due to the deaths of two

of those detainees). On March 7, 2011, the US President issued an

Executive Order for the Periodic Review of Individuals Detained at

Guantanamo Bay Naval Station Pursuant to the Authorization for the Use

of Military Force.

The US President’s decision to sign into law the National Defence

Authorization Act (NDAA) and thereby potentially expand indefinite

detention without trial, and his acceptance of indefinite detention

without trial for certain detainees already at Guantanamo, as well as

detainees in Afghanistan is being heavily criticised by rights

organisations.

Says Human Rights Watch to the Obama administration: “We urge you to

improve the process under which the detainees in Guantanamo or

Afghanistan can challenge their detention. The Executive Order did

provide for some additional process protections for persons currently

detained at Guantanamo, but instead of providing for the assistance of

counsel at periodic review boards, it provides only for a

government-appointed military representative. This is a blatant denial

by your administration of basic due process rights—a denial that is

already occurring in Afghanistan. As in the so-called administrative

review of detention in Afghanistan, detainees subject to the new review

process at Guantanamo are to be denied access to classified evidence,

even if it is used to justify their continued detention”.

Administrative detention in armed conflict

Ashley S. Deeks, International Affairs Fellow, Council on Foreign

Relations and Visiting Fellow, Centre for Strategic and International

Studies (on leave from the Office of the Legal Adviser, US Department of

State) gives an explanation about this issue especially

non-international conflicts that nations such as Sri Lanka faced.

Before making statements on ‘enemy combatants’ in Sri Lanka’s

custody, the United States should have given some thoughts to the

sentiments expressed by Deeks, a legal authority on conflicts that we

are discussing here and the detention of those who are connected with

such conflicts.

He says; “When a State is engaged in an armed conflict, one of the

most important activities that the State may undertake is detention. The

most familiar type of detention during armed conflict is the detention

by one State of its opponent’s armed forces: when possible, a State’s

armed forces will detain their opponents on the battlefield so as to

prevent those fighters from continuing to take up arms. When this kind

of detention occurs during armed conflicts between States, the 1949

Geneva Convention (III) Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War

(Third Geneva Convention) generally provides the rules for such

detentions.(Fourth Geneva Convention)”.

“However, there are a number of other situations in which States

engaged in armed conflict may detain persons without necessarily

bringing criminal charges against them. (This article does not take a

position on whether or when a State should try to prosecute individuals

it has administratively detained.)

This article refers to this type of detention as “administrative

detention.” First, in international armed conflict, a State may detain

certain civilians who appear to pose a security threat to that State.

The 1949 Geneva Convention (IV) Relative to the Protection of Civilian

Persons in Time of War (Fourth Geneva Convention) expressly contemplates

that States will undertake such detentions of civilians.

Second, in non-international armed conflict, the State may detain

individuals engaged in hostile acts against it, such as armed rebels and

individuals that the State deems a serious threat to security. Third,

individuals detained as belligerents in international armed conflict,

but who are not entitled to prisoner of war status, may face detention

without criminal charge until the end of hostilities”.

“A limited set of treaty rules prescribes the procedures a State must

follow in determining when, how, and for how long it may

administratively detain individuals during armed conflict. While the

procedural rules for administrative detention contained in the Fourth

Geneva Convention which apply to “protected persons” in international

armed conflict are reasonably robust, only a very limited set of treaty

rules applies to administrative detention in non-international armed

conflicts. Rather, detention in non-international armed conflict is

governed almost exclusively by a State’s domestic law. Given the dearth

of rules in non-international armed conflict, a lawyer for the

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has proposed a set of

procedural principles that States should apply to all cases of

administrative detention, whether that detention occurs during armed

conflict (either international or non-international) or outside of armed

conflict entirely”.

Indefinite detention: The US scenario

Georgetown University Law Professor Jonathan Turley expressing his

outrage, said: “I am not sure which is worse: the loss of core civil

liberties or the almost mocking post hoc rationalisation for abandoning

principle. The Congress and the President have now completed a law that

would have horrified the Framers.”

“Indefinite detention of citizens is something (they- the Framers of

the US Constitution) were intimately familiar with and expressly sought

to bar in the Bill of Rights.”

Other legal scholars agree about all alleged criminals having Habeas,

due process, and other legal rights in duly established civil courts.

Legal scholars and rights organisations have repeatedly said that

military tribunals are constitutionally illegal. Since June 2004, the US

High Court made three landmark rulings.

In Rasul v. Bush (June 2004), the Court granted Guantanamo detainees

Habeas rights to challenge their detentions in civil court. Congress

responded with the 2005 Detainee Treatment Act (DTA), subverting the

ruling.

In Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, the Supreme Court held that federal courts

retain jurisdiction over Habeas cases. It said Guantanamo Bay military

commissions lack “the power to proceed because (their) structures and

procedures violate both the Uniform Code of Military Justice and the

four Geneva Conventions (of) 1949.”

In October 2006, Congress responded a second time. It enacted the

Military Commissions Act (MCA). It subverted the High Court ruling in

more extreme form.

Undermining fundamental rule of law principles, it gave the United

States administration extraordinary unconstitutional powers to detain,

interrogate, torture and prosecute alleged terrorist suspects, enemy

combatants, or anyone claimed to support them.

It lets presidents designate anyone anywhere in the world (including

US citizens) an “unlawful enemy combatant” and empowers him to arrest

and detain them indefinitely in military prisons.

The law States: “No (civil) court, justice, or judge shall have

jurisdiction to hear or consider any claim or cause for action

whatsoever….relating to the prosecution, trial or judgement of….military

commission(s)….including challenges to (their) lawfulness….”

On June 12, 2008, the High Court again disagreed. In Boumediene v.

Bush, it ruled that Guantanamo detainees retain Habeas rights. MCA

unconstitutionally subverts them. As a result, the US administration has

no legal authority to deny them due process in civil courts or act as

accuser, trial judge and executioner with no right of appeal or chance

for judicial fairness.

Nonetheless, Section 2031 of the FY 2010 National Defence

Authorization Act contained the 2009 Military Commissions Act (MCA). The

phrase “unprivileged enemy belligerent” replaced “unlawful enemy

combatant.” Language changed but not intent or lawlessness to assume

police State powers.

This then is the scenario in the United States whose government is

commenting on the detention procedure in Sri Lanka which ended a

separatist war defeating a brutal terrorist movement called the

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam - LTTE or Tamil Tigers - just three

years ago in May 2009.

The Asian Tribune had no alternative but to expose the double

standards adopted by the United States administration regarding Sri

Lanka’s handling of its non-international conflict. Nevertheless, the

Asian Tribune does not dismiss any nation on this globe its sacred right

to defend itself from terrorism, safeguard its sovereignty and

territorial integrity, planning and executing national security

strategies to prevent repetition of terrorist acts that the United

States and Sri Lanka faced, with the objective of safeguarding its

citizens and award them a peaceful environment.

Courtesy: Asian Tribune |