|

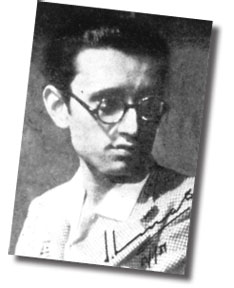

Remembering Manto:

Master of Urdu Literature and Pakistan's D.H Lawrence

By Rushda RAFEEK

If you find my stories dirty, the society you are living in is dirty.

With my stories, I only expose the truth." For anyone who finds Saadat

Hasan Manto's comment outrageous in absolute fashion, then he is not for

you. His words might seem liquorish to taste- like what his mouth begged

for perhaps, he who penned his own epitaph: "Here lies Saadat Hasan

Manto. With him lie buried all the arts and mysteries of short story

writing. If you find my stories dirty, the society you are living in is dirty.

With my stories, I only expose the truth." For anyone who finds Saadat

Hasan Manto's comment outrageous in absolute fashion, then he is not for

you. His words might seem liquorish to taste- like what his mouth begged

for perhaps, he who penned his own epitaph: "Here lies Saadat Hasan

Manto. With him lie buried all the arts and mysteries of short story

writing.

Under tons of earth he lies, still wondering who of the two is the

greater short story writer: God or he." Drawing a question mark with

knitted eyebrows, of course, the plot hovers in a thick cloud as to why

the attention suffers a minimum to Manto following his stellar

contribution serving as a tool of human aspect amid the deft fingered

literature in a language linking only by tongue and not by hearts of its

people, that is, Urdu.

Historian

For even when the veteran film critic and historian Rafique Baghdadi

asks the residents of Byculla in Mumbai today, they question back in the

need to know who Manto is- oblivious to what Manto had, within a short

spell, given the twelve of his later years to film writing for the then

Bombay Talkies and Filmistan.

With so much to hold close to the bosom common to care, this year

commemorated his 100th birth anniversary on May 11. But in contrast how

many of us like the Byculla residents know Manto as one of the most

prolific South Asian literary figures not forgetting his insightful

legacy trailing behind him- once threatened to be cut off?

Toba Tek Singh, a fine example of his ilk, leaps from the page at the

reader with a whiff of his irascibility at play no sooner you start

reading in that moment. Throwing together bravado, less of insensitivity

but what he termed was an undertone of irony to the air, he conveyed, in

every sense, immorality is exactly what a conflict can cause whose

incense was ache, a smoke of shame faintly dropping to mere ash, what

then, had to be cleaned up.

Unbiased stand

Unbiased to stand against what he thought was, in existence and to

march among the profane and be plucked out from the endemic corruption,

Manto reflected concerns for the Partition of the subcontinent in 1947

by the British; taking a bold leap as does

the word literature, most of all, demanding a writer take inventory

beyond sounding precious.

As the years wore on, Manto stumbled upon and between questions

pecking on the quintessence of identifying him, and to whom he now

belongs within the startling dislocation bespattered by the birth of

Pakistan in India's Partition. He was deeply affected and through this

painful daily advance, anointed by the devil in his people, which tore

the rhythm and struck a chord that never will a world be reasonable or

just again.

Toba Tek Singh reveals it all: "One inmate had got so badly caught up

in this India-Pakistan-Pakistan-India rigmarole that one day, while

sweeping the floor, he dropped everything, climbed the nearest tree and

installed himself on a branch, from which vantage point he spoke for two

hours on the delicate problem of India and Pakistan. The guards asked

him to get down; instead he went to a branch higher, and when threatened

with punishment, declared, 'I wish to live neither in India nor in

Pakistan. I wish to live in this tree.'" Toba Tek Singh reveals it all: "One inmate had got so badly caught up

in this India-Pakistan-Pakistan-India rigmarole that one day, while

sweeping the floor, he dropped everything, climbed the nearest tree and

installed himself on a branch, from which vantage point he spoke for two

hours on the delicate problem of India and Pakistan. The guards asked

him to get down; instead he went to a branch higher, and when threatened

with punishment, declared, 'I wish to live neither in India nor in

Pakistan. I wish to live in this tree.'"

Reconciliation

What Manto represented, then, was the urging request for

reconciliation of the divided two. The question becomes, if we develop a

stream of fondling or fury upon reading his bare stripped sensory

details and what we can do with this shameless soul? And here is where

things get threatened as Shakespeare's Feste may reveal a truth, as

jests can do in a harsh world. There was still within Manto an element

analysing of the folly of those around him and what was beneath the

decorous yet pretended friendship of an order conscious discriminating

system.

We hear him drum the loss of heartbeat as one nation by its way of

'ethnic cleansing' through his portrayal of these tragedies by

cultivating an elegance of delight, and mastery at once everything

indeed, with each of them fine and new almost always revealing itself

when we come back. To return to that of anything by Manto is something

vibrant and fresh as rising, but also never really setting. It stays

like an uncleared blood of evidence.

Uncle Sam

In Letters to Uncle Sam that takes form by putting terrible creases

into the garment of American policy with nine letters written in Urdu

between 1951 and 1954, clearly, the lour lipped culprits are brought

forward. Arguing rational matters and giving it square to the face, then

interposes often, in full force, a tight tension of slap stick comedy,

with a psychoanalytic theory- conceptualising two different worlds in

contrast- that of what is enjoyed by the Western American splashed in

the media available and the communists in Pakistan.

His thoughts on the movie 'Bathing Beauty' from the second letter

comes forth: "Uncle, is this how women's legs look like in your country?

If so, then for God's sake (that is, if you believe in God) block their

exhibition in Pakistan at least."

The migration from Bombay to Lahore in January 1948 sadly did not

work in his favour. What was to follow were several chapters of

unsettlement for Manto. He remained desperate to make ends meet for his

family in 'Laxmi Mansions' in Hall Road, only cutting deep the regret in

his collection 'Yazid' he mourns: "My heart is heavy with grief today.

I feel enveloped by a strange listlessness. More than four years ago

when I said farewell to my other home, Bombay, I experienced the same

kind of sadness. I was sorry to have left the place where I had spent

many working days of my life.

Bombay had asked me no questions. It had taken me to its generous

bosom, me, a man rejected by his family, a gypsy by temperament. And the

city had said to me: 'You can live here happily on two paisa a day, or

if you wish, on ten thousand rupees. It is up to you...'." Bombay had asked me no questions. It had taken me to its generous

bosom, me, a man rejected by his family, a gypsy by temperament. And the

city had said to me: 'You can live here happily on two paisa a day, or

if you wish, on ten thousand rupees. It is up to you...'."

Jovial characters

To add, thumping jovial characters into the dough of his short

fiction, Manto's ability to utilise them and mirror a snapshot of the

savagery and human behaviour bespoke none other than, simply, the

present situation those days.

In opening up thought tied to a real-world driven thrust in the works

of Manto for his pimps, swindlers, drunkards, thieves, thick bearded

Sikhs, child prostitutes, degraded women of the patriarchy, half baked

mullahs, murderers, cheating spouses, desperate fathers, liars and

gamblers to help draw pathos in the cold light of uncouth public, brings

my toes to dip into places one sojourns in the hope of what may hold and

move us through the clever in the callow.

A great deal of this is enjoyed in Ten Rupees so seldom heard as if

hit by hard a breeze, absorbing the senses beyond the mere reading of

words than, a distinct yet disturbing view invites us in say, Thanda

Gosht (Cold Flesh), Mozelle, and Khol Do.

Diction

Manto dusted off topics left untouched and if nothing else, that

wanted to be written following the breakthrough of the Partition both

ironically and problematically watered by blunt diction and the lyrical

hem in regard of style.

As he kept observing the matter yet disagreeing with a mind of his

own in a time capable of watching from an extremist's distance, if not,

with an open mouth in horror behind a covering hand.

There were moments of restrictions and moments of political pollution

acting as a fillip. Finding this useful, in the mould of D.H Lawrence,

Manto fought those shores gnawed by human hypocrisy, with it came a

string of rapes on an unwinding spool and mayhem squirting communal

violence and atrocities then rushes into a sunken poignancy washing the

face of exposure away like a footprint when deception makes a fine

camouflage jacket.

Manto was tried for obscenity many times more than a dozen, and yet

never convicted, all because his work learnt the lyrics of those ghazals

no one dances to and be deemed impermissible for society although much

to the amusement ,were sworn to tell the truth, the whole truth and

nothing but the truth, the only honest answer.

Revelation

It is terrifying a revelation; Manto failed his matriculation exam in

Urdu and dropped out of Hindu Sabha College in Amritsar having failed

twice whilst still a freshman. But then how does one pick up the pen and

battle oppressive diseases looming large? It is, soon after meeting,

Abdul Bari Alig, a journalist, scholar and writer, he embraced the

thirst for reading works of the literary heavyweights namely- Chekhov,

Pushkin, Oscar Wilde, Gorky, Victor Hugo, Maupassant and many who

ultimately provided the champions of influence. Manto published

twenty-two collections of stories, three collections of essays with

seven collections of radio plays, some film scripts, letters and a novel

to his name, juggling controversy and criticism stinging as sad an

attempt throughout the spread of a two-decade career.

Tucked in the pockets of literature and that what can be said like

everything else turning sore overnight, Manto remains a forgotten napkin

but daring to remind not something of a gull trap perhaps, what drew a

resisting decay so becomes difficult to remove. People just a few like

Manto with not many years in hand, who toiled to speak for the hopeless

languishing in their chains, let alone expounds the abusive silence we

bring to ourselves and others are less recognised.

Perhaps even more telling, this, when we, with our insincerity in the

cast of mind, accept the devils in ourselves but not an attempt or

thought is cobbled for Manto's, that too not his own but in his written

word as we know it. There again, lies in the human forever separate.

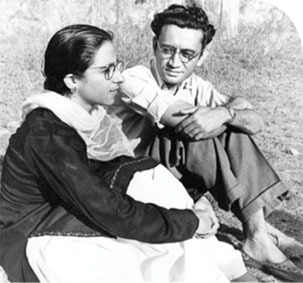

Mesmeric essay

Untimely, journeys begin with the end in mind; like salt which ate

through the grill guarding the windows of actor Ashok Kumar's seafront

house in Manto's mesmeric essay Stars from Another Sky: The Bombay Film

World of the 1940s, inebriety corroded his liver causing cirrhosis to

creep into its walls.

Manto breathed his last in 1955 before his 43rd birthday, although

life for him entailed, only and always, to shake the realism out of

impulsive predicaments- tossing its revolutionary head in the pre and

post colonial subcontinent where this was least considered a right.

But then there is always Camus who you go to listen, who said: "The

pur-pose of a writer is to keep civilisation from destroy-ing itself."

Yet most frankly, in fact, standing by himself, between the

divisional destruction to help maintain the goodness in its absence

where too, the crescent of Manto's love for humanity left unnoticed in

the sherwani of his prose, in some of us, retains the honey in the curd. |