|

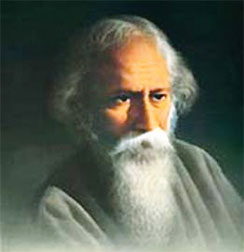

Rabindranath Tagore:

An enduring literary legacy

In this series on the life and times of Rabindranath Tagore whose

150th birth anniversary was recently celebrated, we would, briefly,

explore his increasing relevance in today’s world, his enduring literary

legacy as well as his artistic and cultural vision which has effectively

formed not only the contours of Indian cultural modernity but also the

defining characteristics of the Asian culture. Rabindranath Tagore

(1861-1941) known in Bengali as Robindronath Thakur was born in

Calcutta, India, into a wealthy Brahmin family. Although Tagore was a

genius in his motherland India, he came into universal prominence with

the awarding of Nobel Prize for literature for Gitanjali (Song

Offerings) on November 13, 1913. In this series on the life and times of Rabindranath Tagore whose

150th birth anniversary was recently celebrated, we would, briefly,

explore his increasing relevance in today’s world, his enduring literary

legacy as well as his artistic and cultural vision which has effectively

formed not only the contours of Indian cultural modernity but also the

defining characteristics of the Asian culture. Rabindranath Tagore

(1861-1941) known in Bengali as Robindronath Thakur was born in

Calcutta, India, into a wealthy Brahmin family. Although Tagore was a

genius in his motherland India, he came into universal prominence with

the awarding of Nobel Prize for literature for Gitanjali (Song

Offerings) on November 13, 1913.

Gitanjali, the universally acclaimed literary masterpiece of the

Gurudev was first published by the Indian Society London on November 1,

1912. The next edition of Gitanjali was published by Macmillan and

Company in 1913. Apart from its literary value, Gitanjali encapsulates

the quintessential vision and the philosophy of life of Gurudev Tagore.

Although the initial proposal for Gitanjali was made by Sir Thomas

Sturge Moore, a Fellow of Royal Society, the Nobel Committee was not

satisfied with the selection. “The Chairman of the Committee was,

however, doubtful as to how much of Gitanjali was Tagore’s own creation

as ‘as opposed to being an imitation of classical Indian Poetry’ ”.

However, a Swedish Verner von Heidenstam made a decisive contribution

clearing the doubts about the masterpiece. Although the initial proposal for Gitanjali was made by Sir Thomas

Sturge Moore, a Fellow of Royal Society, the Nobel Committee was not

satisfied with the selection. “The Chairman of the Committee was,

however, doubtful as to how much of Gitanjali was Tagore’s own creation

as ‘as opposed to being an imitation of classical Indian Poetry’ ”.

However, a Swedish Verner von Heidenstam made a decisive contribution

clearing the doubts about the masterpiece.

Verner states, “Just as a selection of Goethe’s poems could well

convince us of Goethe’s greatness, even if we were unfamiliar with his

other writings, so we can say quite definitely of these poems by Tagore,

which we have in our hands this summer, that through them we have come

to know one of the very greatest poets of our age.”

Utmost seclusion

Tagore’s early days of life was spent in ‘utmost seclusion’ which

rekindled his peerless imagination and led to the formation of his

universal and extremely humanist philosophy which was later turned into

practice through the establishment of Santiniketan or Visva-Bharati

University.

In the acceptance speech of the Nobel Prize for Gitanjali, Gurudev

Tagore spoke about his early life; “I remember how my life’s work

developed from the time when I was very young. When I was about 25 years

I used to live in utmost seclusion in an obscure Bengal village by the

river Ganges in a boathouse.

The wild ducks which came during the time of autumn from the

Himalayan lakes were my only living companions, and in that solitude I

seem to have drunk in the open space like wine overflowing with

sunshine, and the murmur of the river used to speak to me and tell me

the secrets of nature. And I passed my days in the solitude dreaming and

giving shape to my dreams in poems and studies, and sending out my

thoughts to the Calcutta public through the magazines and other papers.

And then came time when my heartfelt a longing to come out of that

solitude and to do some work for my fellow human beings, and not merely

give shapes to my dreams and meditate deeply on the problems of life,

but try to give expression to my ideas through some definitive work,

some definitive service for my fellow beings.”

Vision for humanity

A significant aspect of awarding Nobel Prize to Gitanjali was that it

was recognition of the East by the West as a major part of the humanity.

Rabindranath Tagore was well aware of this aspect of the Nobel Prize.

In enunciating his philosophy and vision for India, Asia and humanity

in the acceptance speech he states, “I know that I must not accept that

praise as my individual share. It is the East in me, which gave to the

West. For is not the East the mother of spiritual Humanity and does not

the West , do not the children of the West amidst their games and plays

when they get hurt, when they get famished and hungry, turn their face

to that serene mother, the East? Do they not expect their food to come

from her, and their rest for the night when they are tired? And are they

to be disappointed?

I can remind you of a day when had her great university in the

glorious days of her civilisation. When a light is lighted it cannot he

held within a short range. And India had her civilisation with all its

splendours and wisdom and wealth. It could not use it for its own

children only. It had to open its gates in hospitality to all races of

men. Chinese, Japanese, Persian and all different races. I do not think

that it is the spirit of India to reject any race, reject any culture.

The spirit of India has always proclaimed the ideal of unity. This idea

of unity never rejects anything, any race, or any culture.

It comprehends all, and it has been the highest aim of our spiritual

exertion to be able to penetrate all things with one soul, to comprehend

all things as they are, and not to keep out anything in the whole

universe-to comprehend all things with sympathy and love. This is the

spirit of India.

We have inherited immortal works of our ancestors, those great

writers who proclaimed the religion of unity and sympathy, and say: He

who sees all beings as himself, who realises all beings as himself,

knows truth. Man is not to fight with other human races, other human

individuals, but his work is to bring about reconciliation and peace and

to restore the bonds of friendship and love. We are not like fighting

beasts. It is the life of self which is predominating in our life, the

self which is creating the seclusion, giving rise to sufferings, to

jealousy and hatred, to political and commercial competition. All these

illations will vanish, if we go down to the heart of shrine, to the love

and unity of all races. ”

|