Ulysses, allegorising myth to reality

Ulysses by James Joyce is a popular novel of the 20th century which

is famous, among other things, for Joyce’s innovations in language and

style. However, a salient characteristic of the novel is that it has

extensively used myths to reflect upon reality. Ulysses by James Joyce is a popular novel of the 20th century which

is famous, among other things, for Joyce’s innovations in language and

style. However, a salient characteristic of the novel is that it has

extensively used myths to reflect upon reality.

Ulysses chronicles the passage of Leopold Bloom, the protagonist of

the novel, through Dublin during an ordinary day, June 16 1904, the day

of Joyce’s first date with his future wife, Nora Barnacle.

Ulysses is the Latin name of Odysseus, the hero of Homer’s poem

Odyssey, and the novel draws a series of parallels between its

characters and events and those of the poem.

Since its publication, Ulysses has been subject to literary scrutiny

on its textual innovations and the use of literary techniques such as

stream-of-consciousness, meticulously crafted structuring, and

experimental prose—full of puns, parodies, and allusions, as well as its

rich characterisations and broad humour. It is considered as a popular

English language novels of the 20th century and June 16 is celebrated

worldwide by Joyce fans as Bloomsday.

|

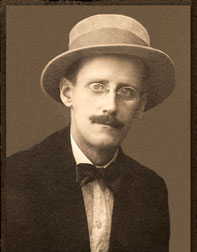

James Joyce |

Writing a lengthy and informative introduction to Ulysses, Declan

Kiberd observes Joyce’s outrage at the evolving political scenario of

the day, “In all likelihood, the stay-at-home English had cannily sensed

that Joyce, despite his castigation of Irish nationalism, was even more

scathing of the ‘brutish empire’ which emerges from the book as a

compendium of ‘beer, beef, business, bibles, bulldogs, battleships,

buggery and bishops’. It is even more probable that, in their zeal to

defend great novelistic tradition of Austen, Dickens and Eliot, they

were as baffled as many other readers by a ‘plotless’ book which had

become synonymous with modern chaos and disorder.”

A seminal characteristic of the novel as observed by Kiberd is,

though it does not seem to have a conventional style of ‘plot’ , it has

, definitely, a single flow and at times, appeared to be ‘over-plotted’.

Kiberd examines, “In fact, Ulysses has a single flow, it may

sometimes seem over-plotted and its ordering mechanisms can appear more

real than the characters on whom they are imposed. Yet, such mechanisms

have been found essential by writers, as a way of containing anarchic

forces of modern life.

It will be seen that Joyce’s highly conscious recuperation of the

story of Odysseus makes possible an auto-critical method, which itself

is central to the book’s critique of authoritarian systems. But, to

appreciate this more fully, it is worth considering Ulysses as the

triumphant solution to a technical problem which, for over a century

before its publication, has exercised the modern European writer. ”

Joyce allegorises the myth of Ulysses to cast his analytical eye on

the unfolding immediate events of the day. Kiberd said; “If the irony of

Ulysses cuts both ways, Joyce was probably more anxious to rebuke

ancient heroism than to mock the concerns of a modern anti-hero.

Odysseus may have been a reluctant warrior, but The Odyssey is

nonetheless a celebration of militarism, which Joyce found suspect,

whether encountered in ancient legend or in the exploits of the British

army.

Bloom’s shaken cigar is finally more dignified than risible, a

reproach to the forces which can cause a peace-loving man like Odysseus

to inflict a wound. To Joyce, violence is just another form of odious

pretentiousness, because nothing is really worth a bloody fight, neither

land, sea nor woman. ”

Joyce underlines his conviction that ‘mythic archetypes are not

exactly imposed by culture but generated within each person’. Kiberd

said, “The universal wish to be original cannot conceal the reality that

each is something of a copy, repeating previous lives in the

inauthenticity of inverted commas (or as structuralists would say,

prevented commas.).

Many early readers, including T.S Eliot, were depressed by Joyce’s

implication that beneath superficialities of personality, most people

were types rather than individuals. He, however, was merely repeating

what Jung had already demonstrated, while adding the important rider

that ‘same’ could somehow manage to become the ‘new’. ”

One of the profound ideas that Joyce reinforces in Ulysses is

‘History as a circular repetition’. Kiberd said, “To many modern minds,

the notion of history as a circular repetition is a matter for despair.

‘ Eternal recurrence even for the smallest!’ exclaims Nietzsche’s

Zarathustra, ‘ that was my disgust at all existence!’. The aimless

circles in which the citizens had walked through Dubliners were symbols

of a paralysis which Joyce hoped he had himself escaped.

Those who believe in progress like to depict the world as moving in a

straight line towards a definable goal. At the basis of the Marxist

distrust of much modernist literature is the suspicion voiced by

Hungarian critic Georg Lokacs, that ‘ it despairs human history,

abandons the idea of a linear historical development, falls back upon

notions of universal condition humane or rhythm of eternal recurrence,

yet within its own realm is committed to ceaseless change, turmoil and

recreation. ”

Myth and fiction

Kiberd argues that ‘autocritical structure ‘of the book is

incongruent with the book’s ‘anti-authoritarian politics’. “The critic

Frank Kermode has contended it is the self-criticism and self-deflation

of modern art which saves much of it from the excesses of romanticism

and fascism. In The sense of an Ending, he proposes a distinction

between ‘myth’ and ‘fiction’, explaining that ‘fictions can degenerate

into myths, whenever they are not consciously held to be fictive.

In this sense, anti-Semitism is a degenerate fiction, a myth, and

King Lear is a fiction.’ By extension it could be said that Ulysses is a

fiction built on the structure of a myth. Joyce’s attempt to submit that

myth to the vicissitudes of everyday life results in a healthy comic

deflation, of both book and myth.” |