|

Binara Full Moon Poya Day on Thursday:

Developing an insight to see life in its true perspective

By Lionel Wijesiri

Impermanence or change is a fundamental concept in Buddhism. Without

a realisation of it, there can never be any true insight through which

we can see things as they really are.

What does it mean “We see things as they really are?” The answer

cannot be put directly into words because words cannot convey the depth

or the transient nature of the experience itself. It would be somewhat

like trying to describe the taste of a strawberry to a person who has

never tasted it. You have to taste it yourself to understand it truly.

|

|

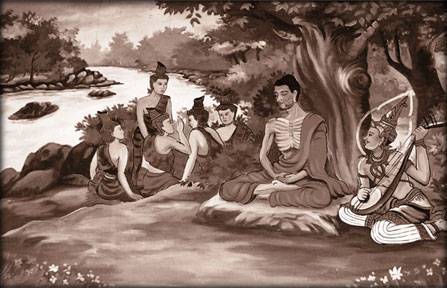

Bodhisatva |

According to the Buddha’s teaching, this liberating insight awakens

one to a deep understanding of the three characteristics of conditioned

existence which are anicca, Dukkha and Anathma. To begin with, the term

‘conditioned existence’ generally refers to the world of time, space,

and form. It is the world in which everything that exists is depending

on certain conditions for its existence. It is the world with which we

are most familiar and some people believe that it is the only world that

exists.

Anicca or impermanence is sometimes stated as “the inherently

changing nature of all things.” But this definition does not go quite

far enough. Impermanence implies not only that reality consists of

things that are always changing; but it also means that change itself is

the essential nature of conditioned existence. In other words, the

universe is not a big machine which is constantly changing; the universe

is more like a symphony, which is nothing but a stream of ever changing

vibrations emerging and disappearing into a background of silence.

Transience of life

The disappointment, despair and frustration in our daily life often

stem from ignorance of the law of nature, which is change or

impermanence. It is, therefore, indeed very important for everyone of us

to understand the nature of change or impermanence to face problems

courageously in our daily lives. It helps us learn how to compromise

with one another. It helps us reduce unnecessary tensions in our

relationships. It helps us to be in harmony with nature and live a happy

life.

Buddhism deals with the problem of impermanence of life in a very

rational manner. Impermanence was the Buddha’s first teaching and also

His last. The first thing He taught His Five Disciples was impermanence,

the fact that everything is changing from moment to moment, and nothing

remains stable. And He demonstrated this as His last teaching by Himself

leaving His body, showing that even the Buddha is impermanent.

The fact of impermanence has been recognised not only in Buddhist

thought, but also elsewhere in the history of philosophy. It was the

ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus who remarked that one could not

step into the same river twice. This remark which implies the

ever-changing and transient nature of things is closer to Buddhist

viewpoint.

Understanding impermanence

The ordinary understanding of impermanence is accessible to all of

us; we see old age, sickness and death. We notice that things change.

The seasons change, society changes, our emotions change, and the

weather changes. Sometimes, realising that an experience is impermanent,

we can relax with how it is, including its coming and going. Seeing that

change is inevitable and it helps us to let go of clinging to how things

are or resistance to change. And sometimes recognising that we are all

equal in being subject to aging, sickness, and death is the basis for

compassion.

When we were young, we were taught that we are going to die someday,

but we live our lives as if we would live forever. Wisdom can come as

people age, not just from life’s experience, but also from increasing

awareness that our lives will end. It gets harder and harder to avoid

this realisation when what remains of our expected lifetime gets

shorter. This often encourages people to look closely at their

priorities and values. Therefore, opening to impermanence in a deep and

profound way can bring tremendous wisdom.

Beyond the ordinary experience of impermanence, Buddhist practice

helps us open to the less immediately perceptible realm of impermanence,

i.e, insight into the moment-to-moment arising and passing of every

perceivable experience. With deep concentrated mindfulness, we can see

everything as constantly in a flux, even experiences that ordinarily

seem persistent.

Deeper experience

In this deeper experience of impermanence, we realise that it doesn’t

make sense to hold onto anything, even temporarily. There’s nothing that

we can hold on-to because everything simply flashes in and out of

existence. We also realise that our clinging and resistance have very

little to do with the experience itself. We mostly cling to ideas and

concepts, not things or experiences in and of themselves. For example,

we don’t cling to money, but to the ideas of what money means for us. We

may not resist aging as much as we resist letting go of cherished

concepts of ourselves and our bodies. One of our most ingrained

attachments is to self, self-image, and self-identity. In the deeper

experience of mindfulness, we see that the idea of self is a form of

clinging to concepts; nothing in our direct experience can qualify as a

self to hold onto.

As we see impermanence clearly, we see that there is nothing real

that we can actually cling to. Our deep-seated tendency to grasp is

challenged and so may begin to relax. We see that our experiences don’t

correspond to our fixed categories, ideas, or images. We realise that

reality is more fluid than any of our ideas about it. As we see impermanence clearly, we see that there is nothing real

that we can actually cling to. Our deep-seated tendency to grasp is

challenged and so may begin to relax. We see that our experiences don’t

correspond to our fixed categories, ideas, or images. We realise that

reality is more fluid than any of our ideas about it.

Five states

The Buddha explained that while we may think of ourselves as single

objects of existence, in fact humans are made up of a collection of five

conditioned, impermanent states: body (Rupa), sense contacts and

sensations (Vedana), perceptions and conceptions (sagnna), volitional

actions and karmic tendencies (Samskaras) and basic consciousness

(Vigñana). These collections (Skandhas) are the true nature of the

person and they are constantly changing. The body grows old, becomes ill

and dies. Sense contacts lead to perception and conception and these are

constantly changing. Our karmic activities never cease and underlying

all these is the basal consciousness, which at death also disappears

with all of the other Samskaras.

The Buddha taught that we should not become too attached to our

bodies and their sensual experiences and thoughts that arise from them,

because the attachment to our bodies and to life causes us great Dukkha

, suffering and misery. Sense contact brings us sense experiences which

we then term as desirable or undesirable.

From this judgement arises the desire to re-experience similar

sensual experiences, which lead directly to attachment. This attachment

then leads to a great thirst or craving for the experience. Soon we are

entrapped in the need to continue such experiences, for we feel we need

or want them. But all experience is very momentary.

Hardly have we grasped onto one, when it disappears and a new

attraction grabs our minds.

Soon we are enmeshed in a great, complex web of desire, all of which

is very transitory, and thus unsatisfactory.

The Buddha advised us that to become free from the constant round of

rebirth and suffering, we would need to realise the changing nature of

things in its true perspective, so that we could free ourselves from the

need for certain experiences, attachment to self and to the illusion of

permanence. |