D. H. Lawrence and the art of poetry

Part 2 Part 2

The second poem by Lawrence that I wish to discuss briefly is The

Ship of Death. It is one of the last poems that he wrote before his

death. It is long and ambitious and in many ways incomplete. However, it

exemplifies what to me is the mature poetic art of Lawrence as

manifested in the latter phase of his career. It blends in interesting

ways, grandeur and calmness, artifice and spontaneity.

The title of the poem refers to the ancient burial practice placing a

symbolic ship in the tomb with the corpse. The intention was that the

ship would carry the dead person to heaven. As I will explain later, the

imagery in the poem carries religious associations shared by many

cultures. Vivian de Sola Pinto says that to communicate poetic

experiences marked by the greatest delicacy, the finest intelligence and

the fullest honesty was his goal, and after several unsuccessful and

partly successful attempts, he achieved the objective in poems such as

Snake and The Ship of Death.

This is how Lawrence begins his poem ‘The Ship of Death’; a sense of

melancholy controls the movement of the thoughts and feelings.

|

|

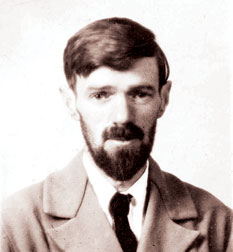

D. H. Lawrence |

Now it is autumn and the falling fruit

and the long journey toward oblivion.

The apples falling like great drops of dew

to bruise themselves an exit from themselves.

And it is time to go, to bid farewell

To one’s own self, and find an exit

from the fallen self.

The tropes of fallen fruit, falling apples, fallen self connect to

generate the theme of the passage of time and life that animates the

poem. And the next few stanzas address directly the inevitability, and

therefore, the need for preparation, for death.

Have you built your ship of death, O have you?

O build your ship of death, for you will need it.

The grim frost is at hand, when the apples will fall

thick, almost thunderous, on the hardened earth.

And death is on the air like a smell of ashes!

Ah! Can’t you smell it?

Note of urgency

Here we detect a note of urgency in the exhortations of the poet .The

poem consists of ten sections and one hundred and seven lines. There is

circularity to the progression of the poetic discourse. It begins with

the inescapable process of ageing, the arrival of the autumn of life,

the inevitability of death and the glimmer of rebirth and self-renewal.

This is how the poem ends.

A flush of rose, and the whole thing starts again.

The flood subsides, and the body, like a worn sea-shell

emerges strange and lovely.

And the little ship wings home, faltering and lapsing

on the pink flood,

and the frail soul steps out, into her house again

filling the heart with peace.

The poem is replete with religious imagery that is not confined

solely to Christianity. The ship of death is a trope that finds an echo

in the sensibilities of diverse religions.(Sarachchandra, for example in

his play Pemato Jayati Soko, based on a Buddhist narrative, made use of

this image as a controlling device).Similarly, the image of the soul

stepping out into its house is one that reminds one of the Upanishads.

It is also interesting to note, that in Jim Jarsmuch’s remarkable film

Dead Man, the concluding sequences focus on death and the dying

protagonist in a boat, drifting by himself, to the sacred spot where the

ocean and sky meet as enunciated in Native American mythology.

The attitude to death inscribed in this poem is one that has provoked

the interest of many commentators. For example, the American poet

Kenneth Rexroth discussing the ‘The Ship of Death’ says that our

civilization is straining to perpetuate the myth that death will not

happen and in our civilization there is a conspiracy to avoid facing it.

In this context of thinking, Lawrence’s poem merits close attention.

Rexroth makes the following assertion. ‘in a world where death had

become a nasty, pervasive secret…..Lawrence re-instated it in all its

grandeur - the oldest and most powerful of the gods. The Ship of Death

poems have an exaltation, a nobility, a steadiness, insouciance, which

is not only of this time but rare in any time.’

Confusion of symbols

Some critics such as Blackmur have complained that there is a

confusion of symbols, a needless clash of imagery in the poem. There is

some substance to this charge, although the confusion could be read as

the manifestation of a deeper ambivalence. What we find in poems such as

the Snake and The Ship of Death that I have discussed is the desire on

the part of Lawrence to fashion a new kind of poetic art that carried

the power of intimate sensuous detail and the fluid movement of emotions

as they succumb to, and resist, the lure of words.

In my last column I made the point that there are two broad

approaches to the poetry of Lawrence that are displayed in the writings

of well-known critics such as R.P. Blackmur, A.Alvarez and Vivian de

Sola Pinto. In recent times, the Indian novelist Amit Chaudhuiri, with

his remarkable book on Lawrence’s poetry titled Lawrence and Difference

has joined the ranks of eminent critics of Lawrence’s poetry. He carves

out a new and potentially more productive interpretive path to the

poetry of Lawrence. As this book is not sufficiently known in Sri Lanka,

except perhaps among a handful of Literary scholars, let me explain its

significance for the benefit of Sri Lankan readers.

To my mind, Chaudhuri’s Lawrence and Difference is significant

primarily for three reasons. First, it is an attempt to examine

Lawrence’s poetry from a theoretically sophisticated post-colonial

perspective. His poetry, by and large, has been commented upon in terms

of the British poetic tradition. This is wholly understandable. However,

with the expansion of the literary critical discourse in modern times,

and the emergence of post-colonial studies as a significant mode of

interrogation, it is important to recognize that Chaudhuri has sought to

bring that perspective to bear on the analysis of Lawrence’s writings.

Second, Amit Chaudhuri is a creative writer of distinction and he has

introduced the importance of the creative process into the conversation

of critical analysis of poetry.

During the past few decades, with the spread of modern literary

theory, the creative process has begun to receive short shrift, and it

seems to me that Chaudhuri has sought to rectify this situation. It is

indeed a welcome move. While reading Lawrence’s political works as a

close reader would, he has also been able to combine it with an

understanding of the complex dynamics of the creative process.

Cultural theory

Third, Chaudhuri has engaged seriously modern cultural theory as

exemplified in the works of such thinkers as Derrida, Foucault Barthes

and Lacan, in his investigations into Lawrence’s poetry. While he is

deeply conversant with their theories and formulations, he is also able

to take a critical distance from their writings to pass critical

judgments on their works. Because of these interpretive strategies on

Chaudhuri’s part, I find his book most stimulating. It is hardly

surprising, therefore, that eminent literary scholars such as Terry

Eagleton have hailed Chaudhri’s work as path breaking. Tom Paulin, the

distinguished poet and critic made the following assessment of this

book.

‘Remarkably, Chaudhuri’s highly sophisticated post-colonial outlook

brings Lawrence’s identification with the colonised subject, the

subaltern, the other, into critical daylight. We see Lawrence, then, as

both modernist and post-modernist. We see that Lawrence’s fascination

with debris and raw material is opposed root and branch - or junk and

wreck - to the work of art as intellectual and immortal monument, which

Yeats advocates.’ He stresses the point that Chudhuri is able to

establish the open-endedness and incompleteness of Lawrence’s poetry

which is in many ways work-in-progress.

Paulin goes on to make the following claim. ‘Reading Chaudhuri, I saw

that here is one of those classic works, such as Frank O’Connor’s The

Lonely Voice or Sean O’Faolain’s The Short Story, in which a gifted

writer takes us deep into the heart of the creative process - theme,

meaning, dreary descriptive and moral paraphrase fall away - and we are

left with the artist at work in the workshop/studio/study. ‘ He goes on

to assert that reading Chaudhuri is like listening to Hazlitt in

conversation with Northcote. The English puritan imagination has here

found a powerfully observant and intelligent critic. It is high praise

indeed!

Amit Chaudhuri’s original intention, as he himself states, was to

examine the sense of place and landscape in Lawrence’s poetry. It was

his goal to chart the way in which his preoccupation with landscape

evolved in his poetry over time. As he was pursuing this objective, he

began to notice certain characteristics peculiar to Lawrence such as

repetitions, words and images from earlier poems obdurately appearing in

later poems, a certain incompleteness and open-endedness. He asked him

the question, ‘was there a way, then, in which the redundancy and

unfinishedness of this discourse could be addressed positively, in a

reading that had other values to affirm than ambiguity, meaning,

felicity of expression, and complexity of treatment and subject matter?’

When he pondered this question he began to realise the importance of

Lawrence’s larger poetic discourse in which the individual poem could be

usefully located. He came to realise the importance of intertextuality.

In his own words, ‘each poem, thus, is intertextual because it has as

its subject matter another poem, or text, made up of a recognisable

assortment of signs which occur within the fabric of the larger

Lawrentian discourse itself.’ In other words, for Chaudhuri,

intertextuality is not only a means of exploring and naming the distinct

discourse in which individual poems can be located but is also a way of

contributing to the production of that discourse. This idea guides his

study of Lawrence’s poetry.

Amit Chudhuiri in his analysis of Lawrence’s poetry invokes

productively certain concepts formulated by modern French cultural

theorists. Let us, for example, consider the notion of trace that plays

so central a role in Jacques Derrida’s investigations. Chaudhuri has

deftly pressed into service this idea. He says that the Derridean notion

of trace that he has deployed suggests that in locutions, images, the

multi-faceted power of the signifier is absolutely and uniquely present;

that is to say, it contains within itself the traces of other

signifiers. What this does is to challenge the self-enclosed nature of

the poem and disrupt the framing devices and locate the poem in a wider

discourse. Chaudhuri offers the following comment.

Intention

‘The language of Birds, Beasts and Flowers, as I have shown, is a

play of traces. My intention has been to move away from this power

structure, of individual readers reading individual poems, as Lawrence’s

own discourse does everything to disrupt it, and demands a more

participatory reading.’ Indeed, this is what he seeks to do in his study

on Lawrence’s poetry. In other words, his critical gaze is focused not

so much on the individual poem - although individual poems are important

- as on the textual system (the phrase is mine, not his). He introduces

a political dimension to this act of disruption. He wants to read

Lawrence’s poems from his vantage point of a post-colonial reader. This

has the salutary effect of turning deconstructive readings into

politically-charged interpretations instead of the purely formalistic

analyses they have become in the hands of many deconstructive critics.

The idea of intertextuality, according to Chaudhuri, is central to

Lawrence’s poetic project. On the one hand, he draws on his earlier

poems; he mines them for locutions, images, prosodic structures. On the

other hand, he draws on other poets such as Walt Whitman, William

Wordsworth and Gerard Manley Hopkins. He recasts these influences in

terms of his own sensibility and sets of priorities. Amit Chaudhuri has

explained the twin forms of intertextuality in Lawrence’s poetry in

great detail. His analyses, at least to this reader, are wholly

convincing.

Another important analytical concept that Chaudhuri has highlighted

in his book is that of participatory reading. As he says, ‘in this

study, I have attempted to move away from the controlling,

interpretative mode of practical criticism that aims at the explication

of particular poems, and have tried to find a form of participatory

reading that both allows for, and addresses, the repetitions and

redundancies of Lawrence’s poetic language. In doing so, I have not

altogether abandoned practical criticism or focus, but attempted to

redefine its intentions and procedures and use them towards

participatory ends.’ While engaging in this project, Chaudhuri had come

to realise that Lawrence’s own concept of art is of it being a discourse

that labours to move towards communality and participation; this is an

attempt to abjure control and power. His poetics consist of

interrogating through its emphasis on difference, the structures of

power incarnated in traditional forms of reading.’ Here Chaudhuri is

calling attention to an aspect of Lawrence’s poetics that has up till

now been virtually ignored by literary critics.

What Chaudhuri is stressing here is the fact that the effort to

situate individual poems in a larger discourse involves a more

participatory reading of the compositions. The objective of such

participatory reading is to locate individual poems in a more

encompassing discourse; the idea is not to interpret or deconstruct them

but rather to participate in the distinctive traits and in the

significance of that discourse. According to Amit Chaudhuri with

exegesis we aim to discover the true meaning of a statement while with

deconstruction we seek to unveil a meaning that was not intended. Both

attempts can be construed as closed and non-communal that encircles

focus. What is kept intact is the controlling power of the reader.

Participatory reading, on the contrary, allows the writer the full

freedom to articulate his or her self within a wider discursive context

that involves the reader. Amit Chuadhuri’s approach to Lawrence’s

poetry, therefore, opens up a newer exegetical space.

Another way of saying this is to claim that Lawrence’s poems are not

formally complete; they are open-ended and unfinished. There are gaps,

silences, and fissures in them and the reader is forced to fill them by

consulting his other poems. That is why the idea of intertextuality is

so important for Chaudhuri as an analytical tool. In Lawrence’s case,

certain poems have more than one version and hence the idea of an

authoritative version is minimized. It makes the situation of the poem

in the larger context in which intertexualities are activated unarguably

paramount.

Amit Chaudhuri, as evidenced in his book Lawrence and Difference, is

an insightful and close reader of poetry. He makes connections between

works of literature that one did not think existed before he pointed

them out. Let us for example consider the connection that Chaudhuri

establishes between Lawrence’s poem 'Snake' and a passage from

Shakespeare’s Macbeth. At first one might tend to regard it as too much

of a stretch. But Chaudhuri makes his case very patiently and

methodically, and I for one am persuaded by his display of points of

kinship. Let us first consider the following lines from 'Snake'.

The voice of my education said to me

He must be killed,

For in Sicily the black, black, snakes are innocent,

The gold are venomous.

And voices in me said, if you were a man

You would take a stick and break him now, finish him off.

And let us compare these lines with the following from Macbeth.

Lady Macbeth; Art thou afeard

To be the same in thine own act ad valor

As thou art in desire? Wouldst thou have that

Which thou esteem’st the ornament of life,

And live a coward in thine own esteem,

Tension

We find the selfsame tension in both the poem Snake and Shakespeare’s

play. In addition both play on words such as king - guest - honour- very

effectively. It is important to bear in mind the fact that Lawrence in

one of his essays made the following comment. ‘It is almost shameful to

confess that the poems which have meant most to me, line Wordsworth’s

'Ode to Immortality', Keats’ odes and pieces of Macbeth or As You Like

It or Midsummer Night’s Dream….’Amit Chaudhuri makes a very good case

for the impact of Macbeth in the structuring of 'Snake'. Similarly, he

makes highly insightful comments regarding Lawrence’s marginality and

his probing into difference as a post-colonial Indian reader of English

prose and verse.

There is much more that can usefully be said about Chaudhuri’s study;

unfortunately, restrictions of space do not allow such detailed

investigations. What I have sought to do in my remarks on Chaudhuri’s

book on Lawrence’s poetry is to underline the fact that it is one of the

most perceptive studies on the subject and we in Sri Lanka can profit

immensely from an examination of his thought-ways.

In these columns, whenever I discuss a Western poet, writer, critic

or filmmaker it has been my practice to discuss his or her relevance to

us in Sri Lanka. So adhering to that practice, let me conclude by

referring to some topics that are deeply connected with our own Sri

Lankan interests. Lawrence is, to be sure, no strangers to us. Some

decades ago Martin Wickremasinghe wrote an important critical study on

Lawrence’s mysticism comparing it with certain traditional Indian forms.

In the 1960s, with the publication of Gunadasa Amarasekera’s Yali

Upannemi, Lawrence attracted a great deal of attention among Sinhala

readers.

And a number of his works have been translated into Sinhala. In

discussing the relevance of Lawrence’s poetry for us in Sri Lanka, I

wish to focus on three points. The first is the question of free verse

or vers libre. D.H. Lawrence wrote a great deal of free verse some of it

bad, some extremely good. Both types, negatively and positively, offer

interesting insights into the dynamics of free verse.

Since the 1969s, free verse has generated a great deal of controversy

among Sinhala literary critics and writers. These controversies were

most acute in the 1960s. G.B. Senanayake introduced this form, and Siri

Gunasinghe gave it greater currency. Some of us, in our own way, helped

to further the conversation on free verse. Speaking for myself, I was a

co-editor of the influential poetry magazine ‘Nisandasa’ and wrote my

first book of poetry as an undergraduate; it was titled Akal Vassa and

was in free verse (Interestingly, it was reviewed in a local Sinhala

newspaper in mock-free verse.)During the past fifty years or so free

verse has come to be accepted by the reading public. Indeed, much of the

poetry now being published in Sinhala newspapers and journals belong to

free verse.

Free verse

The topic of free verse constitutes a complex issue. From the

nomenclature itself to the techniques associated with it , free verse

has generated considerable controversy. Although in English we use the

term free verse as a roomy concept, in French there is a distinction

between vers libre (free verse) and vers libere (freed verse).In

Sinhala, the term nisandas has been subject to diverse analyses. For

example, the authoritative classical work on Sinhala prosody, The Elu

Sandas Lakuna claims that there are hundreds of thousands of metrical

structures. Consequently, what we term a passage of free verse may well

turn out to have its own specific metrical structure that we are unaware

of; that is to say, it is not, technically speaking, a passage of free

verse.

Similarly, the techniques associated with free verse have become the

focal point of much discussion. What Lawrence illustrates, it seems to

me, is that one can be simultaneously the author of good and bad free

verse. Some of his free verse compositions are prosy, lack structure and

are clearly too loose and diffuse to carry poetic conviction. Others

like the poem Snake that I discussed earlier exemplify the sensitive

ways in which free verse can be deployed to communicate an experience

laden with human meaning. Here we are brought to an enlarged awareness

of the potentialities of rhythmic movements. It captures with marvelous

flexibility the flow of thought and rhythms of imagination. Therefore,

it is useful to pay attention to the concept of free verse; it is indeed

one that has exercised a profound influence on modern Sinhala literary

sensibility.

Three of the finest essays on free verse that I have read are by T.S.

Eliot and Graham Hough. Eliot wrote in 1917 an essay titled Reflections

on Vers Libre and in 1942 he wrote another titled, The Music of Poetry.

Hough wrote an essay titled ‘Free Verse’ in the late 1950s. All three

essays still resonate with discerning readers. One of the main points

that Eliot makes about free verse is that it demands imagination,

self-discipline and craftsmanship.

It’s not a case of chopped-up prose masquerading as poetry. As he

asserts ‘as for free verse, I expressed my view 25 years ago by saying

that no verse is free for the man who wants to do a good job. No one has

a better case to know than I that a great deal of bad prose has been

written under the name of free verse’. He goes on to say that only a bad

poet could welcome free verse as a freedom from form. According to him,

it was a rejection of dead form and a preparation for new form or the

renewal of the old. It seeks to stress the inner unity which is unique

to every poem as opposed to the outer unity.

Graham Hough in his essay discusses the prestige accorded to free

verse in the French tradition as opposed to the English tradition, and

the complex prosody involved in, and which underwrites, much free verse.

He begins the essay by asserting that for some reason the concept of

free verse has never wholly naturalised itself in English the way it has

in French. This despite the fact that some excellent free verse has been

written by poets as diverse as T.S Eliot, Ezra Pound, D.H. Lawrence and

Edith Sitwell. Hough points out there are three features that serve to

distinguish free verse from traditional verse.

First, and in many ways the most obvious, the lines are of irregular

length, and that these variations in length do not answer to any

pre-ordained pattern. Second, many of these lines cannot be accommodated

within recognised metrical schemes; that is to say, we cannot label them

iambics, trochaics, anapests and so on.

Third, rhyme is most often absent; if it does appear every now and

then, it has no discernible pattern. He goes on to say that as soon as

one begins to explore actual examples in fair deal, one would become

aware of the fact that a great variety of effects are secured through

these means.

To be continued |