Asinamaali Dreams of an escape

By Dilshan Boange

The magic of the proscenium theatre is that it is a ‘place’ defined

in its ‘spatial dimensions’ yet able to create ‘domains’ through

‘expressions’ that transcend parameters of chronology and geography.

Tales of myth and legend to topics hot in the news, the theatre is a

space where the communication desired by the artist to his audience is

channelled through the medium of ‘live performance’.

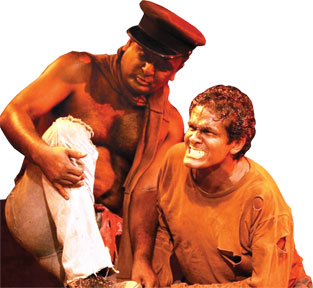

On December 24 seated in the gentle darkness of the Punchi Theatre in

Colombo I watched a Sinhala rendition of the South African play

Asinamaali by Mbogani Negma, adapted and directed for the Sri Lankan

theatregoer by Pujitha de Mel who must be commended for putting on a

praiseworthy production which had in its cast, Priyankara Ratnayake,

Dharmapriya Dias, Vishwajith Gunasekera, Sanjaya Hettiarachchi and

Nishanka Madularachchi. On December 24 seated in the gentle darkness of the Punchi Theatre in

Colombo I watched a Sinhala rendition of the South African play

Asinamaali by Mbogani Negma, adapted and directed for the Sri Lankan

theatregoer by Pujitha de Mel who must be commended for putting on a

praiseworthy production which had in its cast, Priyankara Ratnayake,

Dharmapriya Dias, Vishwajith Gunasekera, Sanjaya Hettiarachchi and

Nishanka Madularachchi.

It can be appreciably noted for its success as an adaptation which

presents the socio-political and cultural landscape the original work

represents, and in fact seeks to communicate while having a distinct

closeness to the local audience through the Sinhala language.

Idiomatic language and colloquy

Overdoing the thrust for connectivity and going overboard with zeal

to make it appeal to our lingual form, a translator could be driven to

‘localise’ the stylistics of speech and dialogue to an extent that the

story almost seems like it was one that happened in Sri Lanka when

paying attention to idioms and colloquy that colour the diction of the

characters.

Yet there can be some noticeable incongruousness when a ‘pristine’

Sinhala speech pattern comes out of characters who communicate of

places, names, and incidents that are utterly unrelated and far removed

from our own milieu and claim to represent another culture.

The translated script of Asinamaali has successfully blended these

different ‘interests’ from my observations of the performance, since I

did not distinctly recall dialogues peppered with Sinhala idioms or

metaphoric expression to the extent that makes the Sinhala translation

and the English text of the play that would undoubtedly show

discrepancies that would raise concerns in terms of ‘transliteration

integrity’, on the part of the ‘adaptor’.

There was colloquialism in the form of certain contemporary slang and

expletives at times which due to the right timing and context made it

function as very direct expressions of the ‘emotion content’ contained

in that character and the moment as opposed to a larger cultural

connotation or culture specific idiom that would conjure an image that

posits the essence of the communication to be strictly limited to our

local sensibilities.

An example to this effect from the English language would be the

saying –‘Carrying coals to Newcastle’ if used to express a Sinhala

consciousness. This turn of phrase while known for its worth as

idiomatic language rooted in the English ‘landscape’ would seem an

oddity if included as a ‘direct translation’ in the course of a typical

Sinhala dialogue. The same could be said in reverse, when gauging a

scenario from another country represented as a translation through the

Sinhala language.

Code mixing and code switching

The verbal element of the performance did not render the play a

purely monolingual Sinhala drama. The dose of mixing words from two or

more languages which gets classified as ‘code mixing’ and ‘code

switching’ (as it is called in linguistics), had a healthy degree to it

which made it realistic and lively, and not overdone.

‘Code mixing’ which can be basically described as where a speaker

inserts a word here and there from another language in the course of

speech that may include references or simple expressions or exclamations

such as ‘My god!’. A common example from everyday life would be when

English words like ‘cool drink’ ‘car park’ ‘telephone call’ are used

instead of their proper Sinhala equivalents, but the bulk of diction and

grammatical structure would be Sinhala. ‘Code switching’ on the other

hand would be where the speaker in the course of the same speech would

seamlessly switch from one language to another.

Looking at the nature of the dialogue in terms of a translated

script, without reading it in terms of the ‘function’ of a certain role,

the instances of ‘code switching’ could be seen in relation to where

white Afrikaner personae are portrayed, and ‘code mixing’ was seen in

the dialogues of non white characters.

|

Pujitha de Mel |

Therefore, in observing this in relation to the very performance I

watched, ‘code switching’ was assigned mostly to the actors Gunasekera

and Ratnayake, the former of the two brilliantly delivering a slightly

Afrikaans accented English that is characteristic of white South

Africans, which materialised when he portrayed a judge.

At certain instances a touch of contemporary Sinhala colloquialism

was detectable in the manner where either the character or the intensity

of the moment validated it to generate appeal to a contemporary

audience.

Instances of ‘code mixing’ such as using the English word ‘shape’ in

the typical contemporary manner of “shape, shape”’ in the modern urban

sense of its usage amongst Sinhala speakers to urge someone to calm down

was very notable and can be appreciated for being appropriate where such

‘lingual realities’ in contemporary Sri Lankan speech patterns are

existent.

Speech elements as that further do not in my understanding subvert

the entire cultural ethos of the original setting of the play as much as

exclusively Sinhala idioms would have.

‘African inclusions’

On the matter of ‘the fabric of language’ in the play, when looking

at its lingual composites as to what was conveyed as both spoken

dialogue and song elements, the performance had a mix of Sinhala,

English and also an African dialect.

The use of words from an African language is no small factor in this

work of theatre albeit in near negligible quantities. Unlike in a book

where the reader may be offered the meaning in footnotes or a glossarial

back note, theatre cannot afford such ‘reference material’ bound to the

work unfolding on stage.

The inclusion of words from an African dialect certainly enhanced the

texture of the play as a translation or adaptation, of a play by a South

African playwright and nuanced to the Sri Lankan viewer the ‘feel’ of a

foreign culture. But in a live performance how does a viewer decipher

the meaning of words which are unfamiliar to him and digest the

narrative without gaping blanks getting imprinted on the viewer’s flow

of comprehension?

When Priyankara Ratnayake began using the word Baabaa as a form of

address to an inquiring officer cross-examining him, and the consistency

of that word as one used to address a person of superior stature posited

its function clearly.

But then one could raise a point of critical argument as to why the

translator didn’t use the Sinhala term Mahaththya or the English word

‘Sir’ which is all too familiarised to the degree of now being a word of

‘modern Sinhala’? Wouldn’t these words be more easily understood by our

local audience and flow more harmoniously with the Sinhala language

framework of the translated script?

An argument as that would have its valid basis no doubt, but it can

be counterproductive as well. An ‘identity marker’ in terms of lingual

elements in that performance as a play which portrays the plight of

oppressed black South Africans came out through that unfamiliar ‘Baabaa’

uttered in servility, fear and submission, and was a marker that

established in respect of terms of address, the status quo in place

between the blacks and whites.

Had that word been supplanted in the translation with a more locally

attuned substitute as mentioned afore, much of the effect that gets

generated of the socio-cultural environs the story ‘was hatched in’

would have been diluted.

Other inclusions of African words came laced as rhythmic threading to

Sinhala lyrics, as small choruses to songs that formed part of the

narrative. In this regard the production was well conceived as to what

would be used as an intelligible word that transpires as a functional

word in the scheme of dialogue and what would serve the purpose of a

decorative ‘sound element’ which generates the African cultural facet in

the narrative outside the ‘dialogic devices’.

Tribal dance

The five inmates did at times erupt into collective tribal dance like

expression that was very much a non-verbal means to express their inner

being and worked in certain ways as communication of their restive

nature as prisoners who longed to be free.

This was clearly a performance that demanded much physical exertion

from the players. The players in giving ‘voice and motion’ to the

characters, collectively brought to life on stage, displays of an

impressive prowess in ‘athleticism’, so to say, that no doubt was

decisive in propelling both the menace and hilarity which swept over the

audience.

The social and cultural context of the story’s setting seemed to have

needed a rather exceptional degree of expression though the means of

body movement as almost a subtext; which was a factor that added much to

the theatricality of the nonverbal narrative aspect of the performance.

The level of agility for acrobatics especially in Dharmapriya Dias

added a dimension of dynamism to his characterisation that made his

persona, at certain climatic moments, to be somewhat ‘larger than life’,

more as a physical entity who through the rhythms of his body’s motions,

shot to sudden ‘crescendos’.

Gunasekera’s talents

The mercurial way in which Vishwajith Gunasekera moved in his

characterisation of various roles such as an apartheid Afrikaner judge,

a jailer, and various other figures, while reverting effortlessly back

to the position of his original form of a hapless black African inmate

beleaguered by a stammer as each ‘enactment’ faded showed the

superlative talent he possess as an actor and deserves applause and

salutations.

While the performance was an overall success in terms of the

techniques devised as stagecraft and the acting delivered by the five

players on stage, I feel it is not unfair to point out that the three

veterans in the cast Gunasekera, Ratnayake, and Dias clearly were on a

noticeably higher level of skill than Sanjaya Hettiarachchi and Nishanka

Madularachchi. I wouldn’t go far to say that the casting was unsound but

the level of acting skill that came out wasn’t on a common wave length.

However, this factor cannot be said to discredit the overall worth of

the performance.

Asinamaali is the name of a rebel leader we are told by the character

portrayed by Priyankara Ratnayake, of whom he is a follower. It was

involvement in rebel dissidence to the white authorities that lands him

in jail. However, the reference to Asinamaali doesn’t become the centre

around which the whole story revolves.

Asinamaali in that sense isn’t an eponymous character. Apart from

being spoken of and referred to, he isn’t a character in the performance

at all.

Significance

The significance of this rebel leader as a figure whose name is the

very title of the work, is I feel, in the fact that the name Asinamaali

represents a symbol of freedom and hope for the oppressed and

incarcerated. Enmity towards the white oppressor is a common sentiment

the inmates share though they aren’t all bound by a common ideological

stance.

The reasons for their convictions are different. And rather

surprisingly some of them do assert that level of difference from one

another on the basis of the wrong committed. But they are the same in

respect of the aspiration they have –to be released from jail.

A prison without walls

I do, however, feel that one of the questions nuanced through the

larger picture is whether being let out of jail is a real freedom for

any of them since the position they occupy in their own land is that of

the oppressed black man.

How big a prison are those five black South Africans really in? Is

the ‘prison cell’ depicted on that stage really the physical parameters

of the ‘imprisonment’ the black South Africans faced under the apartheid

laws? Despite the fact that the five cellmates acted out scenes that

recreated scenarios set in courthouses to pig farms to government

offices to train stations and streets and factories in the big city of

Durban, nowhere was the common black African man accorded dignity and

respect.

A prison can become a place where the convicted lose their right to

assert themselves as humans. The prison institutionalises a human who is

convicted of wrongdoing to be nothing more than a uniform and number in

the eyes of the administration.

The play brings that argument out very overtly. This effacement of

their human worth in the eyes of the controller, the oppressor –the

white man, wasn’t merely restricted to prison inmates in apartheid South

Africa; and wasn’t only within the walls of a prison. The play brings that argument out very overtly. This effacement of

their human worth in the eyes of the controller, the oppressor –the

white man, wasn’t merely restricted to prison inmates in apartheid South

Africa; and wasn’t only within the walls of a prison.

Perhaps all black Africans who suffered under the brutality of

apartheid lived in one big prison where their human worth was sought to

be eroded by the white rulers.

This is nuanced through the final moment of quietening quandary that

grips the inmates as to how they should aspire to lead their lives with

dignity when they are told by the faceless voice of the jail

administration that comes over the loud speaker, about their premature

release on grounds of good behaviour.

Symbolically speaking, could there be a colossal difference in the

freedom those black African inmates will have outside the prison walls

under apartheid?

Storytelling

Everyone has a story to tell, as the saying goes. But who are the

ones fortunate to have their story listened to? And how much of interest

will the listeners genuinely show towards such stories?

Throughout civilisation storytelling has served many purposes in a

community. It is a means to transmit knowledge from one generation to

another and a means of communal bonding. It is also a means of respite

and escape from the tedium of reality.

And looking at the nature of the play, the highly politically charged

background in which the story unfolds, the storytelling brought on stage

through highly articulated stagecraft that narrates through various

theatrical devices the story called Asinamaali, one may venture to say

that perhaps all the above purposes would have been in mind when the

playwright Mbogani Negma intended for a play as the one he wrote to be

performed.

The five cellmates in that prison bring out in the performance the

story that explains why they are in prison.

And that in effect is for each of them to ‘tell his story’ that led

him to be there amongst his cellmates to ‘tell his story’ to them. What

transpires as a result is that the audience hears ‘their story’. Their

story of oppression of being born and living in a prison called

apartheid from which they get no absolute release, unless, they fight

against it. |