|

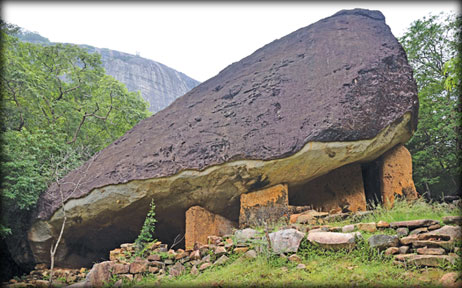

One of the imposing caves |

Namal Pokuna: History atop a hillock

By Mahil Wijesinghe

It was morning and I could see the silhouette of the Dimbulagala

mountain range with its jagged peaks thrusting against the pale blue

sky. The air was a little chilly. The placid water of the Dalukana tank

could be seen on the left side of the road, lying in the foot of the

Dimbulagala hill. Across the tank, a soft, cool breeze blew through the

leaves of trees. The shade and the soothing swishing sound of leaves

mesmerised me. I closed my eyes and breathed in the serenity.

My destination was Dalukana, often referred to as an ‘Adi Vasi’

village, 10 km from Manampitiya, an ancient Adi Vasi village, which was

home to one of the earliest Adi Vasi clans. I was at Namal Pokuna

Rajamaha Vihara, Dalukana, with high expectations of meeting an Adi Vasi

Bhikkhu, Ven. Millane Sri Siriyalankara Thera, who resides in this

temple where Adi Vasis have left marks of their civilisation in caves,

most of which have vanished. Sitting on a bench under a shady mango tree

in front of the spacious compound of the Avasa Ge at the temple on the

foot of the Dimbulagala mountain, the Thera spoke about the temple and

reminisced his childhood with me.

The history of Dimbulagala and its forest hermitage, which had

sheltered thousands of Bhikkhus in the past, dates back to the reign of

King Pandukabhaya. It had been overgrown with creepers after the Chola

invasion and had later become a home for the Adi Vasis.

Millana Yapa, the last chieftain of the clan who lived in these caves

in the Dimbulagala forest for a long time had decided to gift all these

properties to a Bhikkhu along with 12 young Adi Vasi boys, to be

ordained as Samanera Bhikkhus. Ven. Millane Sri Siriyalankara Thera, the

current Viharadhipathi, was one of these 12 boys.

|

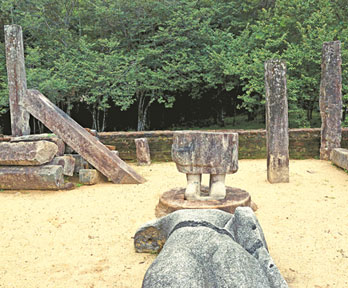

Ruins at the site |

“When we were small, we lived in caves. We didn’t have money. We took

honey, dried meat, maize and fruits such as Mora and Weera to the

Kaduruwela town and sold them, got our provisions and returned to our

caves. Whenever we suffered from any disease, we used our own medicine

based on tribal methods. We bathed in the Avushadha Pokuna (herbal

pond), at the centre of the Dimbulagala mountain, which was believed to

cure all diseases,” the Thera said.

Shrines and hermitages

“These caves were gifted to Ven. Kithalagama Sri Silalankara Thera by

my father, Millana, who was the chieftain of the Adi Vasi village in

Dimbulagala. In place of the caves, he received some mud houses from

areas such as Polonnaruwa and Minneriya. The caves where we lived became

Buddhist shrines and hermitages. Later, my father’s name was changed to

Yapa by the Viharadhipathit because of their close connection”.

“The Viharadhipathi had built a school for us in Horiwila. It was a

very enjoyable life in school,” he said.

Instead of exercise books, those days they carried a slate and a

slate-pencil to school. Returning from school at noon, they would have a

dip in the village tank under the scorching sun, an enthralling

experience for the children.

“I was ordained a Samanera at the age of seven in the Dimbulagala

forest hermitage on June 17, 1965 under the name, Millane Sri

Siriyalankara, along with 11 other Adi Vasi boys. The event received

wide media publicity. However, I am the only one who remains in the

Sasana out of the 12: Some of the others have disrobed while some have

died,” he lamented.

|

The Avushadha Pokuna (herbal pond) |

|

Ven. Millane Sri Siriyalankara Thera |

“My teachers were Ven. Matara Kithalagama Sri Silalankara Thera and

Ven. Udupillegoda Pragnalankara Thera. We got up at 4.00am at the

hermitage. For breakfast, we were given gruel or Kurakkan Thalapa.

“When the Gediya (bell) was rung at around 9.00am, we went for the

Buddha Pooja, and later had our morning meal at the alms hall. Then we

had a short interval around 9.30am, when we would go either to the

Mahaweli river or to a nearby tank to bathe. We would return for the

midday Buddha Pooja and have the midday Dana offered by devotees. Later,

we headed to the Pirivena to study”.

After this conversation, we crossed the main gate of the temple and

started climbing the rocky boulder to explore the ruins of the Namal

Pokuna. The path uphill was dotted with rocky boulders, interspersed

with tall, shade-giving trees.

At last, we saw a man who was the watcher of the Department of

Archaeology, climbing downhill and asked him how far the ruins were. He

merely smiled, shrugged and walked on, but with each stone step we

passed, it seemed that we were going back in time, delving into the

past, to another era. In days of yore, this rock shrine was a reputed

Buddhist pilgrim centre.

Reputed monastery

Around the Polonnaruwa era, it is believed that King Pandukabhaya and

Princess Swarnamali ruled the country from this region. Earlier

Dimbulagala was a reputed monastery for 5,000 Bhikkhus who chose the

hillock for meditation. Almost an hour later, we reached the centre of

the hill where most of the ruins stood amidst the forest canopy. We took

in the charming landscape. The horizontal outline of the Polonnaruwa

ancient city presented a pretty picture against the blue canvas of the

sky. Below, the gleaming lakes, paddy fields, winding rivers, clusters

of villages nestling amid the green carpet were enchanting.

|

Damaged statues in the compound - torsos of the Buddha |

|

Stone pillars at Namal Pokuna |

We explored the natural caves and stone ruins that have made the

Namal Pokuna famous. What caught my attention on the hilltop were

clusters of ruins such as huge torsos of the Buddha, brick stupas, stone

pillars and stone walls almost resting on each other to form a narrow

path through which one could see the beautiful landscape in the flat

land in the centre of the hill.

Walking around the rock wall, we came across a flight of steps which

took us through the forest canopy to the imposing ruins of several

drip-ledged caves and the Avushadha Pokuna, the jewel of the temple. A

large rectangular pond with steps, it was then used by Bhikkhus to bathe

when they fell sick.

The miracle of this pond, I learnt from the Bhikkhu, was that even in

a severe drought, the water never dries up. It is surrounded by several

drip-ledged caves and lies fully covered by the greenery.

The Namal Pokuna area is considered one of the stone architectural

marvels of the Polonnaruwa period. This temple too faced hard times

during the Chola invasion.

The Namal Pokuna Rajamaha Vihara is not yet spoilt by hordes of

visitors and remains a tranquil spot - a confluence of history and

religion. The serenity you experience at the hill is worth the arduous

uphill climb. |