The limits of Berkeley’s idealism

Does a falling tree in the forest make a sound if no one is there to

hear it? This is one of the most quoted and least understood questions

in the history of ideas. Even a man of average intelligence would say

that it is a stupid question because a falling tree would make a sound

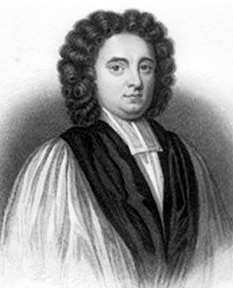

whether there is anyone to hear it or not. However, George Berkeley

(1685-1783) the Irish philosopher and Bishop of Cloyne said a falling

tree would not make a sound if there is no one to hear it. Does a falling tree in the forest make a sound if no one is there to

hear it? This is one of the most quoted and least understood questions

in the history of ideas. Even a man of average intelligence would say

that it is a stupid question because a falling tree would make a sound

whether there is anyone to hear it or not. However, George Berkeley

(1685-1783) the Irish philosopher and Bishop of Cloyne said a falling

tree would not make a sound if there is no one to hear it.

Ronald Knox in his limerick reproduced below took objection to

Berkeley’s view:

There was a young man who said, “God

Must think it exceedingly odd

If he finds that this tree

Continues to be

When there’s no one about it in the Quad.

Not to be outwitted, Berkeley wrote an

equally convincing limerick:

Dear Sir:

Your astonishment’s odd:

I am always about it in the Quad,

And that’s why the tree

Will continue to be,

Since observed by

Yours faithfully,

GOD.

Causal theory

Dissatisfied with John Locke’s causal theory of perception, Berkeley

said it implied a logical gap between the subject and reality. The

logical gap is often called the “veil of perception.” According to the

causal theory, objects in the external world have a causal effect on our

senses and in the process they produce ideas in the observer’s mind.

For instance, when you look at a tree there begins a chain of causal

events starting with the observer’s retina and subsequently in the

neural pathways of the observer. The whole process leads the observer to

see a tree. However, according to Berkeley, the seeing of the tree is a

construct in one’s mind.

|

George Berkeley: Esse est percipi (To exist is to be

perceived) |

In Berkeley’s view, if the tree is a construct in the mind, then what

the observer actually sees is not the real cause of the idea but the

idea itself. Since the observer never perceives anything called

“matter”, but only ideas, there is no material substance supporting his

perception. For Berkeley everything was mind-dependent. If something

fails to be an idea in the observer’s mind, it does not exist. His most

famous adage is Esse est percipi (To be is to be perceived).

Those who did not agree with Berkeley’s theory ask if there were no

material substance behind our ideas, how is it that things exist when no

one perceives them. Berkeley countered the criticism by saying that our

perceptions are ideas produced for us by God. According to him, God

produces everything for us.

Material world

Although we cannot deny the existence of the material world, Berkeley

defended his theory by saying that it makes more sense to deny the

existence of matter than it does to affirm it. In simple words, Berkeley

believed that the material world did not exist. According to him, only

ideas exist. As a result, he has been labelled an idealist. His

idealism, however, has been criticised because we can conceive of things

only in terms of the perceptions or ideas we have of them.

John Locke said that knowledge was derived from experience. However,

Berkeley said all knowledge was limited to ideas because we experienced

things only as ideas. The so-called material or physical states are

perceptions or mental states. He said that pain, the moon and his own

body were a series of perceptions.

Berkeley did not continue his argument to its logical conclusion. If

he had done so, we would have a different picture of reality. Probably

because of his religious background, Berkeley introduced God as a

guarantee that he had a continuing self that is all perceiving.

Universe

In Berkeley’s view, the physical universe does not exist. He

formulated two major structures of thought. One is that mental

substances exist in the form of finite minds and also as infinite mind.

He did not believe in the laws of nature. Most probably he knew the

limitations of his philosophical arguments. So, he called upon God to

solve his philosophical problems.

Berkeley’s philosophy can be summed up as a strict form of idealism.

As an idealist, he avoided some of the difficulties presented by

realism. Idealists argue that there is no external world or universe. To

most other philosophers this sounds absurd because there is enough

evidence to prove the existence of an external world. But an idealist

would say that the Taj Mahal or your own house exists so long as you

perceive it. Berkeley’s idealist theory leads to solipsism, the view

that all that exists is my mind and that everything else is a creation

of my own invention. The view that no physical objects do not exist is

untenable. If physical things do not exist, we ourselves do not exist. A

modern philosopher said solipsism is closer to a mental illness than a

philosophical ideology. |