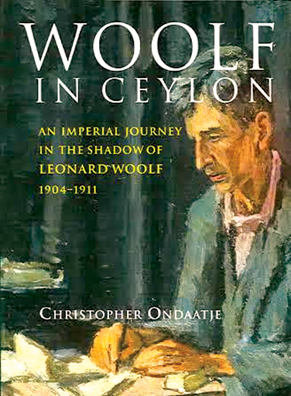

Who's afraid of Leonard Woolf ?

"It was a

strange world, a world of hope and brutal facts, of superstition, of

grotesque imagination; a world of trees and the perpetual twilight of

their shade; a world of hunger and fear and devils, where a man was

helpless before the unseen and unintelligible powers surrounding him."

Leonard WoolfThe Village in the Jungle

It

is a sweltering hot, humid afternoon. There is not much wind. I am

sitting here writing in a wildlife bungalow on the western perimeter of

the Yala National Park overlooking Bandanarewa - a small reservoir only

a few miles for Beddagama (which means literally village in the jungle)

and the site of Leonard Woolf's acclaimed masterpiece The Village in the

Jungle, which was published in 1913 two years after the author had left

Ceylon. Yala's arid and sandy terrain is really of group of five Parks,

covering almost four hundred square miles. It emerged from the reserve

set up at the turn of the last century by British sportsmen interested

in controlled hunting. It's first warden was Henry Engelbrecht who had

come to Ceylon as a prisoner of war in 1905. Because he wouldn't swear

allegiance to the British Crown he was not allowed to return home - so

he stayed on. Woolf described him as "hated", "very stupid" and

"completely without fear and without nerves". He apparently had three

local wives and numerous children. He wasn't much liked. It

is a sweltering hot, humid afternoon. There is not much wind. I am

sitting here writing in a wildlife bungalow on the western perimeter of

the Yala National Park overlooking Bandanarewa - a small reservoir only

a few miles for Beddagama (which means literally village in the jungle)

and the site of Leonard Woolf's acclaimed masterpiece The Village in the

Jungle, which was published in 1913 two years after the author had left

Ceylon. Yala's arid and sandy terrain is really of group of five Parks,

covering almost four hundred square miles. It emerged from the reserve

set up at the turn of the last century by British sportsmen interested

in controlled hunting. It's first warden was Henry Engelbrecht who had

come to Ceylon as a prisoner of war in 1905. Because he wouldn't swear

allegiance to the British Crown he was not allowed to return home - so

he stayed on. Woolf described him as "hated", "very stupid" and

"completely without fear and without nerves". He apparently had three

local wives and numerous children. He wasn't much liked.

Leonard Woolf was born in London in 1880 into a prominent and wealthy

Jewish family. After a spirited five years at Trinity College, Cambridge

where he established lasting friendships with young men like Lytton

Strachey, E.M. Forster and John Maynard Keynes, he applied for the Civil

Service expecting a position with the Home Office. However, with

disappointing examination results, he was only offered a post overseas

and he was sent out in 1904 to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) as a cadet in the

Ceylon Civil Service - an appointed group of white administrators who

ruled the island.

Woolf

disembarked in Colombo and spent two weeks at the Kachcheri (office)

signing letters for the Colonial Secretary. He next set out to take up

his first appointment as a Cadet in Jaffna, a province (one of nine) in

the very north of the island. Jaffna, until recently the devastated

stronghold of the Tamil Tigers (LTTE) in their battle for independence

against the Sinhala controlled island, was in those days an area of

sandy austerity encompassing a ? mile long peninsula that curved towards

the southern tip of India. To get there he traveled by train to

Anuradhapura, and then by mail coach - "an ordinary bullock cart in

which the mail bags lay on the floor and the passengers lay on the mail

bags". The last few miles to the Jaffna peninsula were again by train. A

fierce blazing sun shone down on this flat unforgiving land populated

almost exclusively (except for a few hundred Muslims) by the

predominantly Hindu Tamils. Woolf

disembarked in Colombo and spent two weeks at the Kachcheri (office)

signing letters for the Colonial Secretary. He next set out to take up

his first appointment as a Cadet in Jaffna, a province (one of nine) in

the very north of the island. Jaffna, until recently the devastated

stronghold of the Tamil Tigers (LTTE) in their battle for independence

against the Sinhala controlled island, was in those days an area of

sandy austerity encompassing a ? mile long peninsula that curved towards

the southern tip of India. To get there he traveled by train to

Anuradhapura, and then by mail coach - "an ordinary bullock cart in

which the mail bags lay on the floor and the passengers lay on the mail

bags". The last few miles to the Jaffna peninsula were again by train. A

fierce blazing sun shone down on this flat unforgiving land populated

almost exclusively (except for a few hundred Muslims) by the

predominantly Hindu Tamils.

Woolf spent two and a half years, from 5th January 1905 to 19th

August 1907 attached to the Jaffna Kachcheri responsible to the

Government Agent. He was then twenty four years old and his letters back

home (especially to Lytton Strachey) together with his autobiography

Growing (1961) gave a comprehensive and frank expression of his

thoughts, feelings, sentiments and recall of his time in Jaffna and

indeed his entire seven years in Ceylon. He describes some of his own

liabilities, one of which he believed was "the social defect which I

have suffered from ever since I was a child," ...... namely that he was

mentally and physically a coward.

Community

The white community in Jaffna when Woolf arrived there, consisted of

a dozen Government officers, some ten missionaries, and an ex-army

officer "with an appalling wife and an appalling son". Woolf developed

an outspoken, confident and almost arrogant attitude. Nevertheless, with

his superior Agent away attending to municipal responsibilities, Woolf

was often in charge of the entire province. In a letter to Strachey he

laments "but there is nothing to say to you, nothing to tell you of

except 'events'. I neither read nor think nor - in the old way - feel".

Of these events Woolf mentions the loss of his virginity to a "Burgher"

girl. He developed typhoid; was sent to Bandarawela to convalesce; and

later suffered from chronic malaria. He learned Tamil first during his

stay in Jaffna and Sinhala later after he was promoted and sent to Kandy

on 19th August 1907.

As soon as Woolf got to Kandy he realised that he had entered into an

entirely new world - very different from the "flat, dry, hot low country

with a very small rainfall which comes mainly in a month or so of the

north-east monsoon." Kandy was then a town of 30,000 inhabitants and

unlike Jaffna, was "full of white men". There was an air of European

Cosmopolitanism, which to Woolf was extremely distasteful, and it did a

great deal to complete Woolf's education as an anti-imperialist.

Beauty spot

The climate of course was a great deal better than Jaffna- being

"hill country" and more than 1500 feet above sea level - a "beauty spot"

easily accessible from Colombo. Woolf's sister Bella came out at the end

of 1907 to stay with him - and she stayed until he was transferred to

Hambantota in August 1908. This made a great deal of difference to

Woolf's life in Kandy. Woolf played tennis, squash and hockey, and his

day usually ended at the Kandy Club - "a symbol and centre of British

imperialism". Perhaps the most exalted social responsibility of Woolf

during his stay in Kandy was entertaining the ex-Empress Eugenie of

France showing her the Dalada Maliyana which housed, as it does today,

Buddha's tooth - one of the most sacred of Buddhist relics.

Hosting

Sir Hugh Clifford, the Colonial Secretary, to escort the Empress; and

then later organising an evening of Kandyan dancing at the King's

Pavilion somehow impressed Clifford enough to influence his appointment

as Assistant Government Agent in Hambantota sometime later. Certainly

the most unpleasant work Woolf had to do in Kandy, and indeed everywhere

in Ceylon, had to do with prisons. Hosting

Sir Hugh Clifford, the Colonial Secretary, to escort the Empress; and

then later organising an evening of Kandyan dancing at the King's

Pavilion somehow impressed Clifford enough to influence his appointment

as Assistant Government Agent in Hambantota sometime later. Certainly

the most unpleasant work Woolf had to do in Kandy, and indeed everywhere

in Ceylon, had to do with prisons.

Duties

One of his duties was to be present in a prison when anyone was

flogged or hanged, and to certify that the sentence had been carried

out. "The flogging of a man with a cat-o-nine tails is the most

disgusting and barbarous thing I have ever seen - it is worse than a

hanging." Woolf was repulsed with capital punishment. Although he

believed that law and order should be strictly maintained Woolf believed

that much of British criminal law was an uncivilised method of punishing

and deterring crime.

Woolf's efficiency and organisational abilities after only a year in

the post of Office Assistant in Kandy convinced the Colonial Secretary,

Sir Hugh Clifford, that he should recommend Woolf as Assistant

Government Agent in Hambantota - the youngest AGA in the British Civil

Service.

Woolf arrived in Hambantota as AGA and took over from his predecessor

on Friday 28th August 1908. He eventually left it on leave for England

on Saturday 20th May 1911. It was the third and final phase of Woolf's

stint as a British Civil Servant. Long before this he had almost given

up his weekly letters to Lytton Strachey. The Hambantota district was a

1000 square mile hot, dry, malarial area bounded on the south by the sea

in the south-eastern corner of Ceylon. Again it was different from the

comfortable hill country climate of Kandy and the uncomfortable arid

unprotected Jaffna peninsula. It was almost entirely a jungle area and

had a population of about 100,000. He was given the Residency in

Hambantota to live in on a high promontory jutting out to sea

overlooking the harbour "with walls of astonishing thickness and an

enormously broad verandah and vast high rooms". I know the Residency

well. It is very near the Hambantota rest-house and only about twenty

miles from where I am sitting today in Yala. I have spent many hours at

night listening to the unique smacking sound that the sea made as its

waves rose and fell on the beautiful curved beach below us. It made the

same impression on Woolf.

"All year round day and night, if you looked down that long two-mile

line of sea and sand, you would see, unless it was very rough,

continually at regular intervals a wave, not very high but unbroken two

miles long, lift itself up very slowly, wearily, prise itself, for a

moment in sudden complete silence and then fall with a great thud upon

the sand. The moment of complete silence followed by the great thud, the

thunder of the wave, became part of the rhythm of my life."

There were no other Europeans in the town. Working sixteen hours a

day and being responsible for salt and rice production, education,

combating cattle disease, judging local disputes, and looking after

visiting dignitaries, Woolf made the area the most efficiently governed

in the country. He was tireless and spent his almost three years in the

district riding his horse, walking, traveling in a bullock car and

bicycling over the entire area; his severe administrative work ethic did

not always make him popular but he achieved results and enormous

respect. Woolf also, although he detested big-game hunting, developed a

fascination for the wildlife in the area and for the jungle. Sometimes

alone but often with Henry Engelbrecht, he experience some alarming

encounters in the Magampattu jungle very near here, once literally

digging out a wounded leopard from a cave which Woolf luckily shot at

point blank range when it charged. A terrifying experience.

Woolf's diaries

Every AGA in the island was required to keep a daily diary of his

work. Woolf's diaries with a long erudite introduction were published in

1962. His working day is documented in detail. Being an inveterate

letter writer nearly all other of Woolf's experiences in Ceylon are

thankfully preserved in 125 letters, edited by Frederic Spotts,

published in 1989.

Most

of these, and by far the most outspoken, are those written to Lytton

Strachey. Other revealing correspondence was to Saxon Sydney-Turner, R.C.

Trevelyan, G.E. Moore, Desmond McCarthy and John Maynard Keynes. This

correspondence was an obvious emotional lifeline for Woolf and it is

unfortunate that letters to his family have been lost as they may have

revealed something other than the political and geographical issues of

which he wrote to his Cambridge associates. Most

of these, and by far the most outspoken, are those written to Lytton

Strachey. Other revealing correspondence was to Saxon Sydney-Turner, R.C.

Trevelyan, G.E. Moore, Desmond McCarthy and John Maynard Keynes. This

correspondence was an obvious emotional lifeline for Woolf and it is

unfortunate that letters to his family have been lost as they may have

revealed something other than the political and geographical issues of

which he wrote to his Cambridge associates.

Apart from these letters, his diary, and three short stories

published in 1920 (?) under the title Stories of the East, only the

masterfully empathetic The Village in the Jungle (which many believe had

an authenticity unequaled even in works by Conran and Forster), remained

of Leonard Woolf's writings in Ceylon.

This was until his autobiography Growing was published in 1961 when

he was eighty years old. In Growing Woolf tells the complete story of

his seven years as a civil servant in Ceylon, and it is obvious that he

applied the same method to the towns and jungles as he did to the

Sinhalese and Tamils, and to the strange Anglo-Ceylon society into which

he was plunged when he was twenty-four years old. Today, almost a

century later, it presents a vivid picture of a curious way of life

which has already disappeared. |