Sri Lanka's perennial problem of delayed Justice

Destiny unknown

By Kishani Samaraweera and Zahrah Imtiaz

Today, when one enters into litigation in our courts, one has no idea

as to when one will learn of one's destiny on this critical matter of

one's life. Such is the delay in justice in our country.

How many years have ordinary Sri Lankans waited for their court cases

pertaining to a property issue, or personal relations, or business, to

be finally resolved? How many years have suspects in crimes waited in

remand jail for court cases or preliminary legal proceedings to be

completed to enable their guilt or innocence to be established? How many

kilometres do litigants have to travel from village to court in a

distant town and, how many times in the course of a case?

Society is replete with frustrating and disheartening experiences

caused by the many delays in the system of justice.

Administration of justice in Sri Lanka is burdened with many glitches

ranging from a high backlog of cases in Courts of Law, to overcrowding

of prisons which is seemingly bursting at the seams.

The reasons are numerous, and it is important to fathom the actual

reasons to find lasting solutions. Though it has been considered by many

as a critical social issue, it has not surfaced in a strong manner to

generate a robust debate in society to compel the government to address

them and take immediate measures to mitigate the ill effects of this

persistent problem.

We often use the dictum "Justice delayed is justice denied," coined

by the famous British Prime Minister William Gladstone, and at times, go

further to quote Dr Martin Luther King Jr who said, "Justice denied

anywhere diminishes justice everywhere." All these dicta remain mere

words if we, as a vibrant democracy, fail to take appropriate steps to

resolve the issues at hand.

Delays in legal proceedings have immensely contributed to social

upheavals and even isolation. The financial issues emanating from such

delays are mostly unbearable in many cases and some individuals have had

their lives torn apart due to undue delays.

It is the poor litigant who is at the receiving end while the

governments that have come into power since independence continuously

failed miserably to find practical solutions for this recurring problem.

Most holding high offices would say "this is a perennial problem not

only to Sri Lanka but to the countries of the region" and try to shift

the blame elsewhere.

Delays in dispensing justice would inexorably lead to people

inevitably losing faith in the system and taking the law into their

hands.

At present, according to our sources, there is a massive backlog of

over 65,000 cases pending before the Sri Lankan courts.

When the Sunday Observer contacted a senior legal luminary, who spoke

on the basis of anonymity, he said, "I have tried to resolve the issue

or mitigate it for the last 15 years but it was such a dreaded subject

that I don't want to talk about it.".

Former President of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL) Romesh De

Silva PC refused to comment on the delays of the law. "I have spoken

many times about the issue on different platforms and even addressed the

Bar Association. I don't want to speak about it any more", said De

Silva.

When contacted, the President of BASL, Jeoffrey Alagaratnam said, "We

need more manpower, capacity building and more judges. In addition, laws

and procedures need to be improved."

He said, the system needs to have more processes such as mediation

boards to resolve disputes rather than referring all the cases to court.

E-filing and tracking of cases online will fast track the process and

suggested the need for a system where things are resolved out of court

and the courts are the last resort. This would definitely reduce the

number of cases which get stuck in court, he said. He said, the system needs to have more processes such as mediation

boards to resolve disputes rather than referring all the cases to court.

E-filing and tracking of cases online will fast track the process and

suggested the need for a system where things are resolved out of court

and the courts are the last resort. This would definitely reduce the

number of cases which get stuck in court, he said.

"In Singapore there is a system where postponements carry penalties.

In Sri Lanka, if a lawyer doesn't turn up or the case is unnecessarily

postponed, there is no penalty," said Alagaratnam.

He said, the BASL has frequently recommended various methods to

reduce the trial period. But, compared to the economy and politics,

these things are considered less important and are not the priority of

any government.

Meanwhile, even as the Justice Ministry tries to tackle the problem

of laws' delays, its own proposed amendments to introduce new systems to

expedite the process have been delayed.

Minister of Justice Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe, in January, had reportedly

said, draft legislation to enact new laws and amendments will be

presented to Parliament "within the next two months" but, months later,

this has still not happened.

The Minister last week told the Sunday Observer the bills would

include amendments to the Civil Procedure Code, Motor Traffic Ordinance

and the Mediation Boards Ordinance.

"These things take time. We should be able to do it in the next two

months", reiterated Minister Rajapakshe.

"Law delays are not a new thing. We have been discussing the topic at

various seminars even as far back as the 1950s and 1960s. But now we

have identified key issues that need to be dealt with and we will be

introducing amendments, to address the main concerns," he said.

Attorney-at-Law Gomin Dayasiri's opinion was that when laws are

delayed, the blame is often placed on the courts and judges. He says

delays are sometimes deliberate.

"According to my knowledge, it's only a few judges who will delay a

case. Most times, the delaying is by the lawyers. Political cases are

usually tactically delayed or expedited to get the benefit originating

from the regime in office," he added.

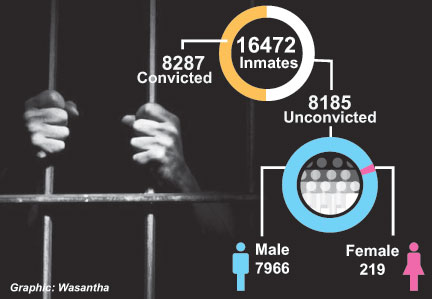

Packed jails

Meanwhile, prison overcrowding today is a result of the ponderous

justice system and its many delays. If the prisons are bursting at their

seams, one reason is that the accused is often remanded in prison before

being tried or convicted.

Minister of Prison Reforms, Rehabilitation, Resettlement and Hindu

Religious Affairs D.M. Swaminathan told the Sunday Observer, "when the

number of remand prisoners increase, there is heavy overcrowding which

then burdens the prisons system."

"At times when prisoners cannot pay even a trifling fine they are

remanded and detained," he said. "We are committed to uphold

international standards prescribed for maintaining prisons and thereby

ensure the dignity of the prisoners," Swaminathan said.

He said, the lack of space for the gradually increasing number of

prisoners is the cause, especially in remand prisons due to the

inability of suspects to pay fines for minor offences.

According to the Minister, the government has drafted an action plan

to carry out prison reforms and is now negotiating with relevant parties

to obtain suitable land for a prison relocation program. Under this,

prisons will be relocated to rural areas. "For example, Welikada Prison

will be relocated to Horana," the Minister said.

He said, suggestions have been made to the President and the Prime

Minister to implement the Malaysian style prison system. The Ministry is

currently working with the Justice Ministry to address issues such as

'no date cases' and overcrowding.

"A task force has been appointed to address these issues. Our

Ministry will co-chair the meetings of the task force which will convene

in the coming weeks," he said.

Swaminathan opined they have suggested that payment of fines be made

in instalments and direct offenders who have committed minor offences to

be involved in social work rather imprisoning them.

The Minister said their main concern is relocating the prisons.

"Drafting laws to ease overcrowding has to be done through the Justice

Ministry and as I mentioned earlier our Ministry has made the necessary

recommendations," he said.

To grant 'bail' or not

A Commissioner of the Legal Aid Commission, also heading the

committee formed by the Justice Ministry on the issue of overcrowding in

prisons, U.R De Silva, told the Sunday Observer there was often

difficulty in obtaining bail, especially with regard to minor offences.

He said the provision on bail contained in the Criminal Procedure Code

was enacted to grant bail as of right.

He said although an Officer in Charge (OIC) of a police station has

the authority to grant bail for minor or other bailable offences, they

do not grant bail, basing their decision on section 14 of the Bail Act.

Section 14 of the Bail Act says if the investigations are not

completed and the Police are of the view that the person will go out and

commit an offence while on bail, or interfere with the witnesses, or the

alleged offence may give rise to public disquiet, the court may refuse

to release such person on bail or upon application.

"On that ground, they can ask the magistrate to decide on the matter

and remand the person even if it's a bailable offence. This leads to the

imprisoning of suspects unnecessarily," said De Silva.

Although the purpose of enacting a Bail Act was to grant bail,it is

not happening as required and expressly stated by the law, he said .

When Police filed a report merely saying section 14 applies the

magistrate would order the suspect to be remanded," he claimed.

As suggestions, De Silva said there must be proper and solid evidence

to show that section 14 will apply in any situation and only then a

person can be remanded. He said, the Magistrates and Police officers

should be educated on this matter. "In grave crimes remanding a suspect

is essential given the nature of the offence. But for minor cases

authorities should not remand people for the sake of remanding," he

added.

De Silva said, the Justice Ministry has formed the commission to look

into this matter and provide suggestions. At present the Police and the

remand authorities are given the opportunity to present their ideas and

suggestions. "We questioned the purpose of the committee when it was

formed. We hope the suggestions will not remain suggestions," said De

Silva.

In terms of Section 5 of the Release Of Remand Prisoners Act (No. 8

of 1991) it is the duty of the Magistrate to visit the prison. It says,

it shall be the duty of every Magistrate to visit every prison situated

within his judicial division, at least once a month.

Deputy President of BASL, Saliya Peiris, explaining the purpose of

such visits to the prisons by the Magistrates, said it is to find out

whether people are detained/remanded unnecessarily and ascertain whether

there are defendants unable to make bail, and he also plays a

supervisory role to ensure the welfare of the prisoners since they are

kept in state custody.

"Prior to making a remand order, the magistrate must apply his

judicial mind and consider whether remanding is necessary and whether in

fact there is sufficient material against the suspect," said Peiris.

He added, sometimes judges use the "weapon of remand" to punish

suspects, "For them, remand is a way of teaching a suspect a lesson.

Some suspects are thrown into remand for trivial offences, even before

they are found guilty, contrary to the presumption of innocence."

Explaining how unnecessary use of remanding will affect people, he

stressed that even after conviction one must see whether the ends of

justice are met by imprisoning people. "The other important question is

whether the prisons really rehabilitate persons. It is not a place where

people come out better," said Peiris.

Postponing Justice

Speaking of another factor causing delays he said, is the fleecing of

litigants by repeatedly postponing cases, lawyer and international human

rights expert Basil Fernando said that prolonged litigation "creates a

culture that encourages lying" and the long years between the commission

of a crime and disposal of the case provides immense opportunities for

unscrupulous litigants and lawyers to engage in many forms of

manipulation.

"The types of manipulations and tricks are varied. For example: a

party that is aware that it has a weak case will want to delay the

trial, with the expectation that, at some point, the opposing party will

get tired and not appear in court," he said.

He said the victims of crime, who already suffered from serious

emotional distress, particularly in cases of rape, murder and similar

crimes, may find it difficult to repeatedly come to courts for many

years. As a result, criminals can slowly get to being acquitted due to

discouragement among complainants or witnesses.

"In some instances, the prosecutors may offer trivial punishments if

the accused is willing to plead for a lesser crime than the one he is

charged with. An example is the granting of suspended sentences for very

serious crimes, including rape," said Fernando.

Also, when the same case is heard by several judges, the judgment is

written by the last judge, who, on some occasions, has not heard any of

the evidence.

"The final judge, who writes the judgment, is unable to appreciate

vital aspects of the trial or could be misled by some unscrupulous

lawyers who, in their submissions, give a version of events not

supported by the actual evidence led in court," he added.

Not having enough, Appellate Courts in the provinces is also another

reason for the laws to be delayed. However, when questioned whether

there is a move to have Provincial Appellate Courts, Minister Wijeyadasa

Rajapakshe said, "We already have several Provincial Appellate Courts,

there is no move to have any more."

Partition actions

Time taken to resolve land issues especially with regard to partition

cases is always highlighted since it takes more than 10 years if the

parties to the action are many. President's Counsel Uditha Egalahewa

agreed that partition actions do take a lot of time to get resolved.

"In such cases, each person's claim has to be established, each party

is entitled to commission of a surveyor and they can challenge the

other's surveyor, then the preliminary plan as to how it should be

divided, takes time. But it is not so in every partition case," he said.

Egalahewa said to solve this issue, the government has now introduced

a system named title registration, which is in operation in some parts

of the country. Still there are issues. "Nevertheless, it is an

effective remedy for these types of complex partition actions," he said.

With the introduction of Labour Tribunals, which became a popular

machinery among workmen, it has enabled to provide speedy settlements of

industrial disputes both collective and individual. It is a good

solution to stop laws being delayed.

According to Egalahewa prior to 1950, before Labour Tribunals came

into being, the only remedy was to ask for damages for termination and

the employee never got back the job. Labour Tribunals are a creation of

the Industrial Dispute Act.

"In 1957, Labour Tribunals were instituted by an amendment where

specific statutory powers were given to order reinstatement. The

litigant will be either compensated or reinstated," he said.

He said, in the Industrial Dispute Act of 1950, the main dispute

resolution was the arbitration procedure and it was not very effective.

It is at the discretion of a political body to refer a dispute through

arbitration and it took fairly a long time.

Former Additional Solicitor General and President's Counsel, Srinath

Perera suggested that the law has to be amended whereby an employer can

terminate the services of an employee without any due reason. "But if he

does so the worker must be compensated with a reasonable amount of

money," said Perera.

He said, Labour Law in this country should be amended according to

the present day requirements.When the Sunday Observer consulted a former

Attorney General as to how the laws delays could be mitigated he said

issues in the criminal justice system can be reduced if a system is

introduced where the Attorney General's Department, Police and

Government Analyst's Department are linked so that the process is more

accurate and speedy.

"Delays in the criminal justice system need to be fixed quickly,

since it can make a dent in the delay", he added.

He said, with regard to civil cases, court houses and judges should

be increased, especially to clear up the backlog of cases retired judges

could be hired, he said.

The Minister of Justice admitted that there is an increase in the

backlog of cases due to the increase in disputes over the years. It

meant that more cases were coming into courts, creating an even bigger

backlog.

"We have opened new court houses and planned to open more to deal

with all these cases", said Rajapakshe.

What people say

Litigants get severely burned by the issues of delays in law and it

disheartens them to go before courts seeking justice. Most continue to

be disappointed in the current system.

Rizni Fareed, 45, from Wanawasala says the last few months have been

a very frustrating time for him and his family of four.

"I didn't want to pursue legal action because I knew a case of this

nature could drag on for years. But when my business partner decides to

go to the Magistrate's Court, I had no option but to support him," he

said.

Today, Rizni says, he has spent more than Rs 60, 000 as lawyers' fees

only to see the case being repeatedly put off.

"We are fast becoming cash strapped and there is no way out," he

lamented. "At this rate we will be spending more than we hoped to get

back from the case."

A resident of Piliyandala aged 80, who sought court intervention

regarding a land issue is still being heard for over 30 years. He said

that now he has lost faith in the existing system and wished he never

initiated such an action. He also blamed the lawyers for dragging the

case.

Another litigant who wishes to remain anonymous expressed her utter

displeasure over the existing judicial proceedings, and said, "I hired a

President's Counsel for my case. I was told that it will take only six

months for the trial to end and it has been three years and the case is

still not settled."

Given her busy life with the job and household chores she said

sometimes she even considered the option of discontinuing the claim.

Coming from a family of lawyers she said, "I have lost track as to how

much I have paid for my lawyer. When they demand we have to pay because

we want this to end soon." |