|

Review of the play Around the World in Eighty Days : Review of the play Around the World in Eighty Days :

Budding talent to enrich English theatre

by Dilshan Boange

Around the World in Eighty Days, the theatrical adaptation of the

classic Jules Verne novel directed by well known theatre practitioner

Thushara Hettihamu and presented by the Royal College English Drama

Society in association with the Old Royalists Association of Dramatists,

had its opening night on August 12, at the Wendt, where it received a

thunderous applause, at curtain call. That evening, under the gentle

darkness, occupying seat Q-7, yours truly witnessed what was truly a

commendable work of theatre, considering the talents on stage consisted

of schoolboys. Around the World in Eighty Days, the theatrical adaptation of the

classic Jules Verne novel directed by well known theatre practitioner

Thushara Hettihamu and presented by the Royal College English Drama

Society in association with the Old Royalists Association of Dramatists,

had its opening night on August 12, at the Wendt, where it received a

thunderous applause, at curtain call. That evening, under the gentle

darkness, occupying seat Q-7, yours truly witnessed what was truly a

commendable work of theatre, considering the talents on stage consisted

of schoolboys.

Hettihamu’s production was based on the script by award winning U.S

playwright and screenwriter Laura Eason, who has to date authored twenty

full-length plays, including originals and adaptations. Eason’s Around

the World in Eighty Days had first been staged in 2008.

Hettihamu’s creative direction of Around the World in Eighty Days

relied much on the effects of lights and audio with effective minimalist

arrangements of props that projected a colourful and active fabric of

performance. The craft devised, which was not of a ‘realist modality’ in

terms of set design and narrative method, evoked glimpses of Dracula,

produced by Ananda drama last year, of which Hettihamu was a

co-director. This director’s ability to unfold a spectacular visual

experience is more or less now a proven fact.

Vision

The vein for an innovative vision for stage was displayed,

especially, in the manner in which the elephant ride through the jungles

of India was presented.

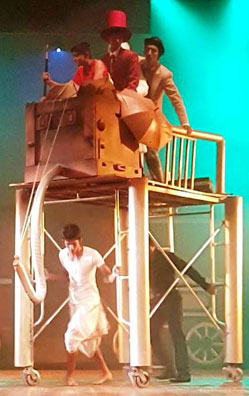

The elephant, devised as a moving platform on shafts with wheels and

fixed with appendages to resemble a pachyderm, was praiseworthy. I

wondered if it might be made part of the curtain call! The play was

certainly a ‘manpower heavy production’. The elephant, devised as a moving platform on shafts with wheels and

fixed with appendages to resemble a pachyderm, was praiseworthy. I

wondered if it might be made part of the curtain call! The play was

certainly a ‘manpower heavy production’.

The theatrical narrative of travel showed theatre craft that relied

on props, at times held in place by a score of extras, for example as

the ship deck railings, to symbolize the passage across the Atlantic.

Royal College, to the best of my knowledge, boasts the largest student

body in any school the world over. Hettihamu thus knew how best to

utilize the strengths at his disposal since theatre in Sri Lanka cannot

as yet hope to see massive scale expenditure to present Broadway stage

techniques and technology, in such stories.

Inaudible

I cannot sincerely say the acting was superlative if discerned in the

context of the larger English theatre scene in Colombo, but it must be

borne in mind in all fairness, that the actors were schoolboys. There

was, to a considerable extent, ‘symmetry in acting talent’ in the

‘fabric of the performance’. While of course it was a production with a

heavy cast of extras, in addition to having certainly more than a couple

of principal characters with notable ‘stage time.’ In general, I

believe, there were no players whose performance was projectile to the

extent of dwarfing another’s performance into the shadows while acting

side by side.

However, it must be noted that a character who was ‘theatrically

colourful’ and somewhat notably compelling was one legged Captain Andrew

Speedy, played by Suneragiri Liyanage. The bursts of liveliness that

exuded from that persona are certainly to the young actor’s credit.

The play’s opening which showed the rigidly undeviating routine of

the protagonist, Phileas Fogg had the audio factor playing to a degree

it overpowered the first couple of lines of dialogue. The beggar woman’s

line “Alms for the poor?” was not intelligibly audible at first

utterance, from where I sat. Another noticeable factor with dialogue

projection was how the street sweeper and flower seller touched on a

cockney accent that was not maintained consistently.

Cockney is not the easiest of ‘English vernacular’ to reproduce in

the Sri Lankan tongue. Neither, is it the most graspable ‘English’ to

our ear. While the character of Fogg’s valet Passerpartout was performed

convincingly, portraying a Frenchman manoeuvring his tongue to be

Anglophone, the Indian accents too were well delivered, I would say.

It must be noted, English pronunciation as one related to class in

British India, just as in England, was nuanced in the play through the

character of the widowed princess, Kamana Aouda, who spoke clear

Standard English indicative of how the upper crust of colonies spoke

English similar to England’s high society. Rivi Wijesekera delivered a

commendable performance as Mrs. Aouda, though his voice projection

slightly emanated the masculinity that belied the saris and dresses. The

ideological currents in Verne’s novel is partly about how man’s will can

prevail over nature through his knowledge in the sciences and

technology, and overcome obstacles that place natural limitations on

man’s desire for conquest of time and space. Around the World in Eighty

Days contains certain colonial outlooks. Verne was after all a product

of his times. It must be noted, English pronunciation as one related to class in

British India, just as in England, was nuanced in the play through the

character of the widowed princess, Kamana Aouda, who spoke clear

Standard English indicative of how the upper crust of colonies spoke

English similar to England’s high society. Rivi Wijesekera delivered a

commendable performance as Mrs. Aouda, though his voice projection

slightly emanated the masculinity that belied the saris and dresses. The

ideological currents in Verne’s novel is partly about how man’s will can

prevail over nature through his knowledge in the sciences and

technology, and overcome obstacles that place natural limitations on

man’s desire for conquest of time and space. Around the World in Eighty

Days contains certain colonial outlooks. Verne was after all a product

of his times.

However, I couldn’t help but note how the turbaned Indian who rang

the bell in the train station was made a comic figure, portraying a

‘numbskull’ to be laughed at. Also, the cortege bearing the funeral

party which was to commit the widow Aouda to a ‘sati pooja’, proceeded

with a gait characterized by a regular ‘group hiccup’ which elicited

sparks of laughter from various quarters in the auditorium, that

evening.

I personally thought it was lamentable when many burst out laughing

when the scene of Bombay unfolded, where vadai sellers came on stage

calling out vadai, vadai as a vibrant set of Indians in turbans and

dhotis brought to life an impression of the East. As easterners

ourselves, whom are we laughing at, and through whose eyes? ‘Colonial

reflexes’ in times said to be ‘postcolonial’? I wail in silence when I

note such responses.

Theatre as an art and a medium is a social engagement of many facets.

Laughter, as a human emotion is not without its politics, as discussed

with philosophical insights in works such as, Milan Kundera’s The Book

of Laughter and Forgetting.

Headwear

What should also be noted about the narrative approach presented by

the play, is that towards the end one sees a small sliver of

‘meta-theatre’ as the policeman is instructed by Inspector Fix to switch

police headwear from a Punjabi police turban to an English ‘bobby’ hat.

The switch of headwear in plain sight, on instruction by a character,

complemented by a change of accent to establish a switch of character,

implies one of the principle markers of ‘meta-theatre’ which is the

admission by the characters themselves that they are in a performance

for an audience.

What was offered to theatregoers in Around the World in Eighty Days,

shows, there is much budding talent to enrich the English theatre in Sri

Lanka. It showed degrees of creativity that speak of more exciting

things to come in the days ahead.

I offer my sincere applause to Hettihamu, the young thespian talent

that came to life on the boards and all who had a hand in bringing to

life a Sri Lankan production of Around the World in Eighty Days. |