The Forbidden City

|

The Forbidden City

|

The universally accepted symbol for the length and grandeur of

Chinese civilization is undoubtedly the Great Wall, but the Forbidden

City is more immediately impressive.

A 720,000-sq.-m (864,000-sq.-yard) complex of red-walled buildings

and pavilions topped by a sea of glazed vermilion tile, it dwarfs nearby

Tian'an Men Square and is by far the largest and most intricate imperial

palace in China.

The palace receives more visitors than any other attraction in the

country (over seven million a year, the government says), and has been

praised in Western travel literature ever since the first Europeans laid

eyes on it in the late 1500s.

Yet despite the flood of superlatives and exaggerated statistics that

inevitably go into its description, it is impervious to an excess of

hype, and it is large and compelling enough to draw repeat visits from

even the most jaded travellers. Make more time for it than you think

you'll need.

The palace, most commonly referred to in Chinese as Gu Gong (Former

Palace), is on the north side of Tian'an Men Square across Chang'an

Dajie. It is best approached on foot or via metro (Tian'an Men Dong,

117), as taxis are not allowed to stop in front.

The palace is open daily from 8:30 am to 5 pm during summer and from

8:30am to 4:30 pm in winter. Regular admission (men piao) in summer

costs 60 ($8), dropping to 40 ($5) in winter; last tickets are sold an

hour before the doors close.

|

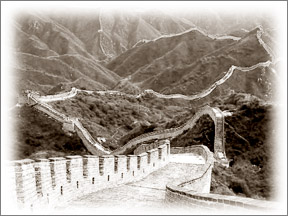

The Great Wall of China

|

Various exhibition halls and gardens inside the palace charge an

additional 10 ($1). All-inclusive tickets (lian piao) had been

discontinued at press time, perhaps in an effort to increase revenues,

but it's always possible these will be reinstated. Tip: If you have a

little more time, it is highly recommended that you approach the

entrance at Wu Men (Meridian Gate) via Tai Miao to the east, and avoid

the gauntlet of tiresome touts and tacky souvenir stalls.

Ticket counters are clearly marked on either side as you approach.

Audio tours in several languages (40/$5 plus 500/$63 deposit; the

English version is narrated by ex-007 Roger Moore) are available at the

gate itself, through the door to the right.

Those looking to spend more money can hire "English"-speaking tour

guides on the other side of the gate (200-350/$25-$44 per person,

depending on tour length).

The tour guide booth also rents wheelchairs and strollers at

reasonable rates. Note: Only the central route through the palace is

wheelchair-accessible, and steeply so.

The Big Makeover

Beijing recently launched an immense $75-million renovation of the

Forbidden City, the largest in 90 years, to be completed in two phases

(the first by 2008, the second by 2020).

Work started on halls and gardens in the closed western sections of

the palace in 2002, with the most effort concentrated on opening the

Wuying Dian (Hall of Valiance and Heroism) in the southwest corner of

the palace, followed by Cining Huayuan (Garden of Love and Tranquillity)

next to the Taihe Dian.

No one can say exactly when visitors will be allowed in; all you can

do now is peer through door cracks on the left side of the outer court.

Plans also call for the construction of new temperature-controlled

buildings to house and exhibit what is claimed to be a collection of

930,000 Ming and Qing imperial relics, most now stored underground.

Welcome as the project is, China's track record of tacky restorations

has made many people nervous. Shortly after the plans were announced,

the China Youth Daily launched a call for public hearings to approve the

details, claiming in typical language that any changes to the complex

"will have psychological influences on all Chinese people."

The suggestion was politely rejected, but an incongruous coat of

bright red paint recently slapped over parts of the palace's Gate of

Heavenly Purity indicates that more input might not be a bad thing.

Background & Layout: Construction of the original palace buildings

began in 1406, during the reign of the Yongle emperor, and took an army

of workers 14 years to complete.

A single moat, 52m (171 ft.) wide and nearly 4km (2 1/2 miles) long,

surrounds it. Between 1420 and 1923, the palace was home to 24 emperors

of the Ming and Qing dynasties. The last of these was Aisin-Gioro Puyi,

who was forced to abdicate in 1912 but was allowed to remain in the

palace for several years afterward.

The Forbidden City is arranged along a north-south meridian, aligned

on the Pole Star.

The Qing court was unimpressed when the barbarians designated

Greenwich Royal Observatory as the source of the prime meridian in 1885;

they believed the Imperial Way marked the center of the temporal world.

Major halls open to the south.

Furthest south and in the center is the symmetrical outer court,

dominated by immense ceremonial halls where the emperor conducted

official business. Beyond the outer court and surrounding it on both

sides is the inner court, a series of smaller buildings and gardens that

served as living quarters.

The palace has been ransacked and parts destroyed by fire several

times over the centuries, so most of the existing buildings date from

the Qing rather than the Ming. The original complex was said to contain

9,999 rooms, testament to the Chinese love of the number nine, and also

to an unusual counting method.

The square space between columns is counted as a room (jian), so the

largest building, Taihe Dian, counts as 55 rooms.

The Inner Court

Using the Western method of counting, there are now 980 rooms. Only

half of the complex is open to visitors (expected to increase to 70%

after repairs are completed in 2020), but this still leaves plenty to

see.

(Nei Ting)-Only the emperor, his family, his concubines, and the

palace eunuchs (who numbered 1,500 at the end of the Qing dynasty) were

allowed in this section, sometimes described as the truly forbidden

city.

It begins with the Qianqing Men (Gate of Heavenly Purity), directly

north of the Baohe Dian, fronted by a magnificent pair of bronze lions

and flanked by a Ba Zi Yingbi (a screen wall in the shape of the

character for "eight"), both warning non-royals not to stray inside.

Beyond are three palaces designed to mirror the three halls of the Outer

Court.

The first of these is the Qianqing Gong (Palace of Heavenly Purity),

where the emperors lived until Yongzheng decided to move to the western

side of the palace in the 1720s. Beyond is Jiaotai Dian (Hall of Union),

containing the throne of the empress and 25 boxes that once contained

the Qing imperial seals.

A considerable expansion on eight seals used during the Qin dynasty,

the number 25 was chosen because it is the sum of all single-digit odd

numbers. Next is the more interesting Kunning Gong (Palace of Earthly

Tranquility), a Manchu-style bedchamber where a nervous Puyi was

expected to spend his wedding night before he fled to more comfortable

rooms elsewhere.

At the rear of the inner court is the elaborate Yu Huayuan (Imperial

Garden), a marvelous scattering of ancient conifers, rockeries, and

pavilions said to be largely unchanged since it was built in the Ming

dynasty. Puyi's British tutor, Reginald Fleming Johnston, lived in the

Yangxin Zhai, the first building on the west side of the garden (now a

tea shop).

From behind the mountain, you can exit the palace through the Shenwu

Men (Gate of Martial Spirit) and continue on to Jing Shan and/or Bei Hai

Park. Those with time to spare, however, should take the opportunity to

explore less-visited sections on either side of the central path. Most

of this area is in a state of heavy disrepair, but a few buildings have

been restored and are open to visitors.

Most notable among these is the Yangxin Dian (Hall of Mental

Cultivation), southwest of the Imperial Garden.

The reviled Empress Dowager Cixi, who ruled China for much of the

late Qing period, made decisions on behalf of her infant nephew, the

Guangxu emperor, from behind a screen in the east room. This is also

where emperors lived after Yongzheng moved out of the Qianqing Gong. |