Analysis of Pablo Neruda's poems; 'Las Alturas de Machu Picchu' -

Part 1

'The Heights of Machu Picchu' is a long narrative poem forming book 2

of Pablo Neruda's monumental choral epic, Canto general (general poem),

a text comprising 250 poems and organized into twelve major divisions,

or cantos. The theme of Canto general is humankind's struggle for

justice in the New World. 'The Heights of Machu Picchu' is itself

divided into twelve sections and it is written in free verse. 'The Heights of Machu Picchu' is a long narrative poem forming book 2

of Pablo Neruda's monumental choral epic, Canto general (general poem),

a text comprising 250 poems and organized into twelve major divisions,

or cantos. The theme of Canto general is humankind's struggle for

justice in the New World. 'The Heights of Machu Picchu' is itself

divided into twelve sections and it is written in free verse.

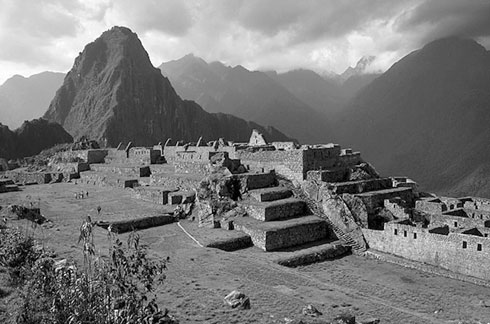

The poet, adopting the persona of the native South American man,

walks among the ruins of the great Inca city Machu Picchu, built high in

the mountains near Cuzco in Peru, as a last retreat from the invading

Spanish conquerors. It is a poem of symbolic death and resurrection in

which the speaker begins as a lonely traveller and ends with a full

commitment to the American indigenous people, their Indian roots, their

past and their future. This week's column (Part 1) will examine the

first six poems.

I

From the air to the air, like an empty net,

I went on through streets and thin air, arriving and

leaving behind, at autumn's advent, the coin handed out

in the leaves, and between spring and ripe grain,

the fullness that love, as in a glove's

fall, gives over to us like a long-drawn moon.

(Days of live brilliance in the storm

of bodies: steels transmuted of bodies: steels transmuted

into silent acid:nights raveled out to the final flour:

battered stamens of the nuptial land)

Someone expecting me among violins

met with a world like a buried tower

sinking its spiral deeper than all

the leaves the color of rough sulfur:

and deeper yet, in geologic gold,

like a sword sheathed in meteors

I plunged my turbulent and gentle hand

into the genital quick of the earth.

I bent my head into the deepest waves,

dropped down through sulfurous calm

and went back, as if blind, to the jasmine

of the exhausted human spring.

This first part of the sequence opens with the image of an empty net,

sifting experience but gathering nothing. This opening reveals that the

speaker is drained by the surface of existence. He searches inward and

downward for a hidden "vein of gold." He then sinks lower, through the

waves of a symbolic sea, in a blind search to rediscover "the jasmine of

our exhausted human spring," an erotic symbol associated with a lost

paradise.

II

While flower to flower gives up the high seed

and rock keeps its flower sown

in a beaten coat of diamond and sand,

man crumples the peal of light he picks

in the deep-set springs of the sea

and drills the pulsing metal in his hands.

And soon, among clothes and smoke, on the broken table,

like a shuffled pack, there sits the soul:

quartz and sleeplessness, tears in the ocean

like pools of cold: yet still

man kills and tortures it with paper and with hate,

stuffs it each day under rugs, rends it

on the hostile trappings of the wire.

No: in corridors, air, sea, or roads,

who (like crimson poppy) keeps

no dagger to guard his blood? Anger has drained

the tradesman's dreary trafficking in lives,

while in the height of the plum tree the dew

leaves its clear mark a thousand years

on the same waiting branch, oh heart, oh face ground down

among deep pits in autumn.

How many times in the city's winter streets or in

a bus or a boat at dusk, or in the densest

solitude, that of night festivity, under the sound

of shadows and bells, in the very cave of human pleasure,

have I wanted to stop and seek the timeless fathomless vein

I touched in a stone once or in the lightning a kiss released.

(Whatever in grain like a yellow history

of small swelling breasts keeps repeating its number

ceaselessly tender in the germinal shells,

and identical always, what strips to ivory,

and what is clear native land welling up, a bell

from remotest snows to the blood-sown waves.)

I could grasp only a clump of faces or masks

thrown down like rings of hollow gold,

like scattered clothes, daughters of a rabid autumn

that shook the fearful races' cheerless tree.

I had no place to rest my hand,

none running like linked springwater

or firm as a chunk of anthracite or crystal

to give back the warmth or cold of my outstretched hand.

What was man? Where in his simple talk

amid shops and whistles, in which of his metallic motions

lived the indestructible, the imperishable-life?

The second poem contrasts the enduring world of nature with the

transitory goals of human beings, who drill natural objects down until

they find that their own souls are left dead in the process. The speaker

recalls that in his urban existence he often stopped and searched for

the eternal truths he once found in nature or in love. In city life,

humans are reduced to robotic machines with no trace of the "quality of

life" in which Neruda believes. The question of where this quality of

life can be found remains unanswered for three further poems. The search

for truth, in the poet's opinion, is a gradual and humbling process.

III

Lives like maize were threshed in the bottomless

granary of wasted deeds, of shabby

incidents, from one to sevenfold, even to eight,

and not one death but many deaths came each man's way:

each day a petty death, dust, worm, a lamp

snuffed out in suburban mud, a petty fat-winged

death entered each one like a short spear

and men were beset by bread or by the knife:

the drover, the son of seaports, the dark captain of the plow,

or those who gnaw at the cluttered streets:

all of them weakened, waiting their death, their brief death

daily and their dismal weariness each day was like

a black cup they drank down trembling.

This search for truth is the subject of this third poem, which

confronts modern humankind's existence directly. This existence is

likened to husking corn off the cob. Urban dwellers die "each day a

little death" in their "nine to five, to six" routine life. The speaker

compares a day in the life of the urban people to a black cup whose

contents they drain while holding it in their trembling hands. In this

poem, Neruda prepares the way for the contrasting image of Machu Picchu,

which is later described in its "permanence of stone."

IV

The mightiest death invited me many times:

like invisible salt in the waves it was,

and what its invisible savor disseminated

was half like sinking and half like height

or huge structures of wind and glacier.

I came to the iron edge, the narrows

of the air, the shroud of fields and stone,

to the stellar emptiness of the final steps

and the dizzying spiral highway:

yet broad sea, oh death! not wave by wave you come

but like a gallop of nighttime clarity

or the absolute numbers of night.

You never came poking in pockets, nor could

you visit except in red robes,

in an auroral carpet enclosing silence,

in lofty and buried legacies of tears.

I could not in each creature love a tree

With its own small autumn on its back (the death of a

thousand leaves),

all the false deaths and resurrections

with no earth, no depths:

I wanted to swim in the broadest lives,

in the openest river mouths,

and as men kept denying me little by little,

blocking path and door so I would not touch

with my streaming hands their wound of emptiness,

then I went street after street and river after river,

city after city and bed after bed,

and my brackish mask crossed through waste places,

and in the last low hovels, no light, no fire,

no bread, no stone, no silence, along,

I roamed round dying of my own death.

The fourth poem shows the speaker enticed not only by "irresistible

death" but also the life and love of his fellow men. This love remains

unachievable as long as all he sees in his fellow men is his daily

death. His own experience in an urban context progressively alienates

him from others, dragging him street by street to the last degrading

hovel, where he ultimately finds himself face-to-face with his own

death.

V

Solemn death it was not you, iron-plumed bird,

that the poor successor to those dwellings

carried among gulps of food, under his empty skin:

something it was, a spent petal of worn-out tope,

a shred of heart that fell short of struggle

or the harsh dew that never reached his face.

It was what could not be reborn, a bit

of petty death with no peace or place:

a bone, a bell, that were dying within him.

I lifted the iodine bandages, plunged my hands

into meager griefs that were killing off death,

and all I found in the wound was a cold gust

that passed through loose gaps in the soul.

The short fifth poem defines this kind of death even more closely in

a series of seemingly surrealistic images, leaving a final vision of

modern life with nothing in its wounds except wind that chills one's

"cold interstices of soul." In this poem, the speaker is at his lowest

spiritual point in the entire sequence.

VI

Then on the ladder of the earth I climbed

through the lost jungle's tortured thicket

up to you, Macchu Picchu.

High city of laddered stones,

at last the dwelling of what earth

never covered in vestments of sleep.

In you like two lines parallel,

the cradles of lightning and man

rocked in a wind of thorns.

Mother of stone, spume of condors.

High reef of the human dawn.

Spade lost in the primal sand.

This was the dwelling, this is the place:

here the broad grains of maize rose up

and fell again like red hail.

Here gold thread came off the vicuña

to clothe lovers, tombs, and mothers,

king and prayers and warriors.

Here men's feet rested at night

next to the eagles' feet, in the ravenous

high nests, and at dawn

they stepped with the thunder's feet

onto the thinning mists

and touched the soil and the stones

till they knew them come night or death.

I look at clothes and hands,

the trace of water in an echoing tub,

the wall brushed smooth by the touch of a face

that looked with my eyes at the lights of earth,

that oiled with my hands the vanished

beams: because everything, clothing, skin, jars,

words, wine, bread, is gone, fallen to earth.

And the air came in with the touch

of lemon blossom over everyone sleeping:

a thousand years of air, months, weeks of air,

of blue wind and iron cordillera,

that were like gentle hurricane footsteps

polishing the lonely boundary of stone.

Here, quite abruptly, the mood of the poem begins to rise in the

sixth section as the speaker climbs upward in space toward the heights

of Machu Picchu and backward in time toward the moment when that ancient

city was created. At that moment in time, past and present lines

converge. Here, "two lineages that had run parallel" meet and fuse.

That is to say that the line of inconsequential human beings and

their petty deaths and the line of permanence in the recurring cycles of

nature. Machu Picchu is the place where "maize grew high" and where men

gathered fleece to weave both funereal and festive garments.

What endures in this place is the collective permanence those men

created. All that was transitory has disappeared, leaving only "the

lonely precinct of stone."

|