The poet and misogynist: A Kunderian theorem

By Dilshan Boange

One of the great successors to the fiction writing form(s) of the

‘magically real’, that to a great extent finds its roots in the fiction

of Franz Kafka, is the Czech born author Milan Kundera.

As a practitioner of the art of fiction writing in the modernist and

postmodernist traditions Kundera’s contributions to the world of

contemporary literature is monumental especially when it comes to

exploring the newer forms of the novel that have evolved in the latter

part of the 20th century in Europe.

|

|

Milan Kundera |

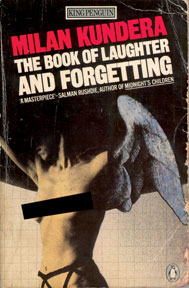

One of Kundera’s most well loved works The Book of Laughter and

Forgetting is a quasi –biographical work that blurs the lines (at times

in the course of the narrative) between fiction and biography. Part five

of this novel which is titled –Litost a most intriguing perspective is

presented through the argumentative dialogues of some rather eccentric

characters.

The scene is set in Prague where Kundera tells us (as the narrator of

the story) the greatest poets of the country had met in ‘the Writers

Club’ and a great many engagingly engrossing conversations spiral as the

poets sit at a table laden with bottles of wine.

An aspect that is rather interesting in this episode is that Kundera

has named these poets with the names of many esteemed figures in

European literature. They are presented to us as –Voltaire, Petrarch,

Boccaccio, Goethe, Verlaine, and so on.

Central argument

One of the topics that come up in the course of this scene is from

‘Boccaccio’ after listening to an incident related by ‘Petrarch’ about a

young girl who had stalked him to his apartment at night to profess her

admiration to him.

Boccaccio scorns Petrarch for having been gentle to the young lady

and for not having been stern with her in rebutting her improper conduct

and goes on to accuse Petrarch for being a woman worshiper.

It is from this point in the narrative a theorem of sorts is put

forward by Boccaccio of how men are (in his beliefs) categorised in

relation to their attitude(s) towards women, more specifically in terms

as lovers, one may understand. The division according to Boccaccio is

specified in the following words –

“Men have always been divided into two categories. Worshippers of

women, otherwise known as poets, and misogynists, or, more accurately,

gynophobes.” What is interesting is how Boccaccio goes on to expound his

theorem by elaborating the different ways that the two types have in

their perceptions in respect of how they view women and what they value

of women. The fundamental quality that is at the centre of this division

is said to be ‘femininity’.

According to the words of Boccaccio the worshippers or the poets

revere women for their femininity and qualities that typify the image of

woman in the very traditional sense of male perceptions.

Feminine feelings such as motherhood, homeliness, fertility, the

divine voice of nature, and even ‘sacred flashes of hysteria’ are seen

as some of these womanly qualities that the poet would value and admire.

These are seen as qualities worthy of reverence, veneration and thus one

could say develops a sense of the poetic.

Boccaccio says that the poets or worshipers can bring into the life

of a woman drama, passion and tears. Understandably, one may conjecture

that a person who is disposed in a more poetic and artistic sense would

create moments of drama and impassionedness through their ways in

dealing with people and responding to emotions both their own and of

others.

Yet these qualities are said by Boccaccio to be what cannot bring

happiness to a woman! And says it is only with a misogynist, who is in

fact troubled by the very idea of idealising the femininely virtuous

traits of a woman, that a woman can be happy.

Defining the misogynist

The argument may seem rather undeveloped from the mundane point of

approaching it through the given term ‘misogynist’, which of course

means a person who hates women, and it is this very point that Kundera

has addressed through the words of his character Boccaccio who explains

–“Misogynist don’t despise women. Misogynist don’t like femininity.” And

going on this line explains further that while the main interest of the

poet is the ‘femininity’ of a woman, while the misogynist prefers the

‘woman’ to her femininity.

This presents a rather interesting framework of conceptions to

theorise on gender politics. When Kundera through the voice of his

character Boccaccio presents the outlook of misogynists as ones who

‘always prefer women to femininity’ there is a certain divorcing of the

character quality of femininity from the human being –the woman.

Therefore, it appears to imply a sense of limiting the woman as a

primarily physical entity who is preferred for that physicality rather

than for any aesthetic sense her character may offer, which seems to be

what the poet in contrast to the misogynist would prefer. By my

understanding the primacy being given to the physical dimension of the

female being (by the misogynist) is a strong statement on the aspect of

sexuality and carnal desire being of paramount to the misogynist while

the poet could be fancifully afloat with his poetic veneration of the

woman whose femininity inspires him. This presents a rather interesting framework of conceptions to

theorise on gender politics. When Kundera through the voice of his

character Boccaccio presents the outlook of misogynists as ones who

‘always prefer women to femininity’ there is a certain divorcing of the

character quality of femininity from the human being –the woman.

Therefore, it appears to imply a sense of limiting the woman as a

primarily physical entity who is preferred for that physicality rather

than for any aesthetic sense her character may offer, which seems to be

what the poet in contrast to the misogynist would prefer. By my

understanding the primacy being given to the physical dimension of the

female being (by the misogynist) is a strong statement on the aspect of

sexuality and carnal desire being of paramount to the misogynist while

the poet could be fancifully afloat with his poetic veneration of the

woman whose femininity inspires him.

Probable view of the misogynist of woman

Why then does the text of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

propound that a woman can be happy only with a misogynist? Giving though

to this line of argument one can suggest it is bound with the aspect of

physical gratification.

Of what good would the poet be to the woman who desires physical

satisfaction when the man is preoccupied with worshipping her femininity

and perhaps not fulfilling her need to feel that her physicality is

fully indulged in and in return made to feel gratified? What good would

a night of serenading and gentle sensuousness be to the woman whose

desires are about satisfying erotic carnal fantasies? Would the

misogynist be the type of man who could make a woman happy going by this

line of argument? If so why? It seems that when the inner being of

femininity and the virtues which the poet reveres in the woman is

stripped of her, she is primarily a form of flesh. It is this desire for

the most primordial sense that creates the scale of who would a woman be

happier with? Does this suggest somehow that the woman desires to be

seen as ‘flesh’ and thus in some sense dehumanised? Certainly, such a

suggestion will be one that will be contentious in many respects.

However,there is a strong suggestion in the Kunderian text that the

satisfaction sought on the part of the woman (mainly as expounded by the

voice of Boccaccio) is not for the genteelness offered by the kind as

the poet, but the approach of the misogynist who by indulging in the

aspect of ‘woman’ (devoid of femininity) would probably make the female

feel ‘more of a woman’ than the poet would through his lofty ways that

may be more of a surreal (and even spiritual) indulgence than a strongly

bodily one.

Female body as an object of desire

Thus it seems that the theorem of the character of Boccaccio is that

the fundamental happiness required by a woman is to be gratified in

terms of her being as ‘woman’ giving primary focus to her physical,

bodily being. Perhaps this perspective is telling of the modern

perceptions of European society where the human body and at that the

female body is objectified greatly for purposes that range from artistic

to commercial.

And perhaps in Kundera’s understanding the modern woman desires to be

more affirmed of her value in terms of her physical, bodily attributes,

which can very well be even thought of as ‘assets’ given certain modern

perceptions and priorities in society which is evident at times by the

importance that is placed in presenting the woman as a sexually

appealing image, as women themselves would at times see it fitting.

Therefore, the question of objectification comes into focus. Does the

woman desire to be objectified, especially as a physical entity

understood in terms of sexual appeal? It seems that according to

Kundera, the female psychology he very subtlety hints at, suggests that

the woman would very much feel a ‘woman’ when she is made the object of

a man’s desire, and at that carnal desire.

And by this line of thinking we can believe that it is the ‘man’ the

male, who affirms and validates the female of her womanliness, and the

happiness of such a woman (in Kunderian argument spoken through

Boccaccio), is fulfilled by the misogynist and not the poet.

An episode from Nadine Gordimer’s July’s People

In regards to the line of discussion developed in this article I

would like to cite a certain scene from the novel July’s People by the

South African Nobel literature laureate Nadine Gordimer.

Having to flee the city life after civil unrest a white South African

family takes refuge in the backward rural community of their servant

named July. Having to adapt to what is pretty much life in a ‘mild

wilderness’ the family finds themselves transforming into more rugged

beings deprived of their previous modern amenities and luxuries.

‘Bam’ the father discovers his abilities as a hunter and in one

instance hunts a wart-hog and makes a spit roast of it. Having enjoyed

the fresh roasted meat of their kill in the great outdoors that night

the husband and wife make love for the first time after they fled the

city to the life in the bush.

The end of the scene tells us that after the night of copulation that

had obviously been one of some considerable physical, bodily intensity

Bam wakes up in the morning and “...had a moment of hallucinatory

horror...” seeing blood on his manhood and thinking it was that of the

pig he had killed only to realise instantly that it was in fact of his

wife. What can one deduce from this scenario? Surely it is obvious that

the ruggedness of the wild was making the masculinity of Bam reach deep

into some hidden primordial sense which would have been heightened by

the experience of hunting and roasting the prey which could have awoken

a sense of alpha maleness.

And the lovemaking thereafter, that very night, could have evoked a

sense of the primordial in a way that made the aspect of the physical be

stripped of all genteelness.

I remember in the final year in university this novel being a text

discussed in class in a lecture by Shamima Zubair, I contended that the

act of lovemaking on the part of Bam was possibly a crude parody of the

Bam as the hunter where his wife is seen as the prey –the meat, the

flesh that he will conquer through his masculine prowess. In my own

words it was ‘she was the pig’.

After all why would he immediately be struck by the thought of the

blood on his member being of the pig he killed? It is a manifestation of

the subconscious which may have been giving way for Bam to awaken the

savageness in his male being owing to the circumstances that impel him

to be more bound to the rugged life in the bush. However, there should

be no misunderstanding the novel of Gordimer suggests that the wife felt

to be a woman fulfilled in terms of her desires.

There is nothing in that episode in July’s People to such effect as

to affirm Boccaccio’s words in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. But

it maybe demonstrative of the misogynist as per Kunderian description

which I believe is a point worth considering in terms of literary

analysis.

Poet or the misogynist: Who is better?

Who of the two? –the poet or the misogynist, is capable of bringing

happiness to the woman may be a question with no definite answer.

Perhaps it is a question that the fairer sex is better positioned to

answer. I remember mentioning this theorem of the poet and the

misogynist to some of my batch mates who read English, and all of them

who were there at that moment being ones of the fairer sex were in

favour of the poet saying that the misogynist would be one who would

seek to crassly objectify the woman as opposed to the poet who would

idealise the worth of a woman for what she is beyond the physical frame.

However , there was a dissenting view, by one –Farah Macanmaker who

said, the poet could be equally bad as (if not even worse than) the

misogynist, since the poet could in his devotedness to idealise the

woman and praise her virtues in his own subjective perceptions

stereotype the woman, and further believe that he must ‘possess’ her and

thereby make himself to be the one in rightful ownership over the woman.

Such possessiveness could become daunting, surely, regardless of how

sweet the serenading may be.

|