|

observer |

|

|

|

|

|

OTHER LINKS |

|

|

|

Ruined towns look to Beirut, mostly in vain

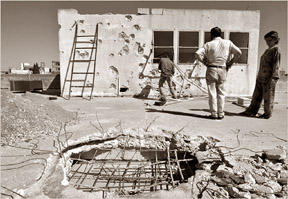

A ride through the south of Lebanon, across rutted and bombed-out roads, past a landscape of twisted metal and crumbled concrete, reveals little progress toward rebuilding tens of thousands of homes devastated by the 34 days of Israeli bombing that ended more than six weeks ago. Money has begun flowing in, from foreign governments and nongovernmental organizations. But nearly $900 million in international pledges remains untapped by the Lebanese government, whose presence is barely visible in the south. In contrast, Hezbollah. With money from Iran, continues to give cash payments to individual Lebanese for damaged homes. And the central government has allowed, and indeed encouraged, some foreign countries to begin giving similar grants. Those villages lucky enough to have been adopted by foreign donors are preparing to rebuild. In those less fortunate, villagers sit staring into ruins, and waiting. "There is nothing from the government, not even a phone call," said Muhammad Azzam, mayor of Siddiqin, a small village that has reported 449 homes destroyed by Israel's military. Such comments are repeated, nearly verbatim, across the south, although an arm of the Lebanese government has cleared rubble from many towns. International pledgesThe government defends its performance, saying that it has gotten vital services such as water and electricity back, opened roads and kept the economy functioning. It says that it is nearly done putting in place the trustworthy financial system needed to tap into the international pledges, one that will provide a level of accountability and transparency unprecedented for Lebanon.

"It has only been one month, and a lot has been accomplished," said the country's finance minister, Jihad B. Azour. "But people only see what wasn't done." However, when it comes to homes, the government has been slow to respond. Government officials said they would pay $40,000 cash for each destroyed house, but they have not been able to say when. And winter is approaching. The United Nations resolution that ended the war was designed in part to give Lebanon's central government its first chance since Israel withdrew in 2000 to extend its authority over the southern part of the country. The peace deal required the government to dispatch the internationally bolstered Lebanese Army there to push out Hezbollah, long the de facto authority in the area. The agreement also offered the central government a chance to sweep in and begin to rebuild, which could have helped it win the peace among a population that it had long ignored. But while the army is there, it has yet to really engage the international force, not yet allowing it to set up checkpoints or conduct searches. The central government has made no better showing at winning over the people of the south with help. Officials in Beirut, determined to get projects moving, have simply encouraged donors to bypass the central government. "We are trying to make ourselves flexible," said Dr. Azour, the finance minister. So far, foreign countries have agreed to adopt 99 out of 251 damaged villages, and will likely spend about $640 million on the work, officials said. The United States has agreed to spend $20 million to help repair the Mudarrij Bridge in partnership with the Italians, for example. In total, the United States has pledged $230 million in humanitarian assistance and what are known as early recovery systems. Raw emotionsLebanon's people largely rallied together after Hezbollah's capture of two Israeli soldiers on July 12 prompted Israel to rain bombs on their country, shattering bridges, airports, homes, roads and businesses. But Lebanese unity is as fleeting as the raw emotions aroused by crisis. Now the scars of this war have exposed, and in some cases deepened, many of the nation's fault lines. Some Christian villagers in the Shuf Mountains, for example, ask why Shiites in the south will receive compensation for lost homes after just a month, when many of those Christian villagers have received nothing for homes they lost during the civil war of the 1980's, officials said. The animosity has only grown between Hezbollah and the coalition that controls the government - named for March 14, the day in 2005 that huge numbers of people demonstrated to call for an end to Syria's military presence. Their verbal sparring has raised fears of possible civil conflict, in a country miserably familiar with such fighting, and has distracted attention from rebuilding, officials said. "We have a responsibility to stop political bickering and work on not turning Lebanon into a battleground for external conflicts, and at the same time build a strong, democratic and capable country," Prime Minister Fouad Siniora said in a televised speech on Friday night. "Our country needs reconstruction of the people's houses, their lives, their businesses, their sources of income, reconstruction of infrastructure, reconstruction of economy, rebuilding our future potentials." That point is not in dispute; the debates are over how to get there. And so the March 14th side accuses the Hezbollah side of carrying water for Syria and Iran. The Hezbollah side accuses the March 14th side of doing the United States' bidding. Terms like flattened, crumbled and collapsed barely describe what happened to Aita al Shaab, a Hezbollah stronghold in the south, and neighbouring villages. The landscape is a canvas of destruction, 750 homes destroyed, 400 damaged. Communities have been uprooted, families forced to crowd in with relatives, schools shattered. Many residents worried that reconstruction would be uneven, with little planning, and villages forced to take what they can get. Fadhl Chalak, the former president of Lebanon's Council for Development and Reconstruction , charges that the government has intentionally stalled the reconstruction effort. He quit the development council, he said, after Arab countries pledged hundreds of millions of dollars in aid before the war ended and the government was slow to accept it - which the government also denies. The government has guaranteed that every village will be rebuilt, but the current patchwork of aid has raised concerns about the fate of villages that are not adopted. "We do not believe people will be compensated," he said, flatly. "We do not believe their houses will be rebuilt." (New York Times) |