Whitewater thrills

The road to Umphang twists and squirms like a headless python as it

climbs the hills of Thailand's mild west. First it zags to the left and

then tightly zigs right, tossing us like tin cabs in the front seat of

the pick up truck. For four hours we ride on its slithering ridges

blanketed on three sides by a wet jungle cloaking shrieking bugs and

screaming birds. The road to Umphang twists and squirms like a headless python as it

climbs the hills of Thailand's mild west. First it zags to the left and

then tightly zigs right, tossing us like tin cabs in the front seat of

the pick up truck. For four hours we ride on its slithering ridges

blanketed on three sides by a wet jungle cloaking shrieking bugs and

screaming birds.

We had flown to the border town of Mae Sot at dawn, where the driver

picked us for this ride to the valley of Umphang. Forget direct flights

or air condition coaches - there is no easy path to nowhere.

We meet our guides before noon. "It's been raining hard for the last

two days" one of them grins as he loads the rubber rafts and supplies on

the truck. He smiles conspiratorially. "That means more water, and more

fun."

Tourists don't come to Umphang; only adventurers do. The road trip is

an appetizer for the thrills and spills of a whitewater rafting trip

down the MaeKlong river, whose frothing drama attracts hundreds of souls

looking for a test of bravery every year.

Two water-falls help mark Umphang on the map the Tilosu, a gigantic

favourite among local travellers; and the Tilolae, our destination, a

cascading wonder hidden in deep forest and reached only by braving the

swift-flowing river. This rigor makes the Tilolae less popular, less

traversed, and yet more symbolic as it stands in virtual secrecy

awaiting a handful of daring pilgrims.

We are lucky to have stumbled across some of the best guides in the

area. Indeed, Boonlam Yodmuang and Seri Intrakasem are more than just

guides - they're local legends. Ten years ago the duo embarked on a

Homeric journey as they navigated a bamboo raft through the gaeng, or

rapids, of the Mae Klong and discovered the uncharted magnificence of

Tilolae. "We didn't 'discover' it," Boonlam corrects me playfully.

"It had been there for ages." Back then they had to spend five

arduous days and make countless stops, for their raft kept falling

apart. Now it takes two days at most on rubber "rubber" that makes the

trip far less dangerous and much more exciting.

All is set by noon. It is a joyride during the first few hours, and

we take time marvelling at the lush landscape. The mae Klong carves a

deep gorge through the upper part of Thung Yai Naresuan, Thailand's

pristine forest reserve famed for its striking wilderness. All is set by noon. It is a joyride during the first few hours, and

we take time marvelling at the lush landscape. The mae Klong carves a

deep gorge through the upper part of Thung Yai Naresuan, Thailand's

pristine forest reserve famed for its striking wilderness.

Teak tress shoot up in the sky, creepy ferns coil around trunks, wild

orchids boast sensual blooms and life bursts forth from the banks. I

spot the radiant plumage of a kingfisher, then a hawk a couple of a

barbets, an army of monkeys. As our raft cruises past a fig tree we hear

a trumpeting "whoomp-whoomp", and look up to find a horn-bill fluttering

by. Boonlam points at a clearing where a deer lies covered in dry blood.

"Probably a tiger," he whispers.

By late afternoon the river gets mean, turning in sharp angels,

forcing our steersmen to exercise their paddling skills. Just before we

get to the campsite the Mae Klong puts up its first test: at Lekatik, "a

narrow pass" in Karen tongue, the water picks up steam. First it looks

as if we are running into a limestone wall, but the river swings ahead

to the right, revealing a stretch of rock-strewn rapids.

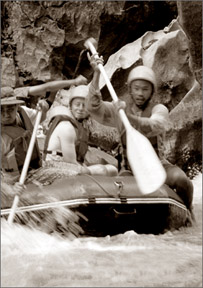

"Take the right channel," Seri shouts to Boonlam, then turns to me.

"Hang on tight". Our raft goes in first. It waltzes into the dancing

currents like a staggering drunkard. as Boonalm and Seri sink their

paddles hard to negotiate the planned course.

After the first clash I assume that it's over, but a series of

aftershocks ensues in what seems like flashes of a second. The Lekatik

rapids aren't a fiery slam-bang descent, but a succession of turbulent

steps - a stormy corridor flanked by high walls that requires rafters to

maintain balance throughout their length.

Suddenly our raft emerges onto placid water and makes another right

turn where the river widens up again. I look back and watch the other

three boats emerging successfully behind.

That night we camp in a peaceful clearing just past Lekatik, and the

next morning we rise with a sense of euphoria, revived and fully

prepared for a whole day of rough rafting. "It'll be the real thing from

now on," Seri says.

"The rapids will be Grade IV to a mild degree of Grade V. They're

even tougher in the rainy season. We spent three days at this section of

the river when we first came down in our bamboo raft. I take that as a

warning - the real danger of whitewater rafting is complacency.

Soon our aquatic caravan reaches the Jed Muen rapids, another long

tapering pass with rocky obstacles. Emboldened by fresh energy, we

breeze past the staccato stream almost gently not with a scream, but

laughter.

That doesn't last long, though, as the joyous mood is quickly drowned

by the thunderous roar of water ahead. The notorious Bandai rapids are

just round the corner. Boonlam, at the front, looks back at Seri and

signals to the right. His raft mate nods and zooms in.

Bandai is drop-down monster, a one-shot test of maneuvering deftness.

Before I even realize, we plunge almost face-first into a cauldron of

foaming water. My heart drops to my feet as we move backwards and the

stern of the boat rakes helplessly against a black rock.

"Let it spin! Let it spin! Seri shouts. The currents push the raft

free from the shallows and we clumsily complete a merry-go-round to

regain the bearing, with Boonlam back at the front. Both steersmen now

paddle hard to get away from the commotion.

But we aren't through yet - that was just the first Bandai rapid; the

second is howling 200 meters ahead. In my estimation this one is

slightly lees monstrous, yet is it's another nerve-tin-gling hydro-drop

. Seri and Boonlam don't make it difficult this time though,

soft-landing the raft in proper orientation and soaking us thoroughly

with cold water adrenaline.

Another challenge faces the group when we make an approach to the Hin

Yod rapids. Seri senses something unusual in the movements of the water

so Boonlam scouts the condition downstream. Ten minutes later he comes

back with the news; It's impassable because of a piece of spiky rock

protruding just under the channel it must have fallen recently, so we

have to drag the rafts over and round.

Afterwards, the river allows us a break, letting us cruise in a

leisurely fashion and admire the scenery of a thickening forest. An hour

later we hear it, a noisy disturbance signalling the Hak Sok rapids - a

classic shaped gully with two successive swings.

Boonlam again leaves the boat to inspect the situation. This time he

comes back and signals the go-ahead.

The drawn a mental image of the rapids, but that's nothing compared

to its overwhelming presence as we enter. "Keep to the right, and cut to

the left after the curve," Seri commands from the rear.

The raft bobs rhythmically as we swing hard along the right bend,

only to encounter a granite deal end where the river whirls at a

devastating angle to the left. For a fleeting moment I feel as if we're

about to be sucked into the froth of a hidden alcove, but Seri yanks

vigorously to turn the boat into the open passage, scraping on the rock,

then uses his paddle to thrust us away from the trap. A few more pushes

and we're whipped out of the rapids.

The Kon Mong rapids are last, a stretch of rocky, bumpy and exciting

turbulence standing guard before the Tiloae waterfall. Spurred by the

imminence of our destination, the four rafts drive into the clamor,

their passengers roaring zestfully against the rumble of the torrents.

Sri and Boonlam seemingly infected by this renewed enthusiasm, deal

deftly with the twists and turns, the whirlpools and eddies, until the

final obstacle is cleared and we emerge into the embrace of verdant

surroundings again. The pacific water seems like a blessing and,

strangely, we feel as if this is the easiest cross we've made during the

entire journey.

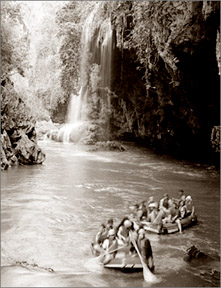

We reach the Tiloae late in the afternoon. A mystical veil of

sprinkles shrouds this steep, pouring waterfall like fading memory.

Contemplating its might, I realize we're but tiny elements of humanity

belittled by this exemplum of natural wonders. I am humbled and grateful

to be here.

The next morning we trek back to Umphang, a 25-kilometre walk out of

the jungle. The summer sun shines ferociously through the foliage, the

mysterious bugs shrieking and strange birds squawking. Crossing a small

stream, Boonlam walks towards me, smiling conspiratorially. "Come back

again after the rainy season," he says jovially.

"There will be more water, and certainly more fun."

The Wild Side

|