Blair's fear over Bush 'poodle' label revealed

Tony Blair has felt unable to pick up his US Congressional Gold Medal

of Honour for four years partly because the ceremony would reinforce the

prejudices of those convinced he was "some sort of poodle", says Sir

David Manning, Britain's Ambassador in Washington. Tony Blair has felt unable to pick up his US Congressional Gold Medal

of Honour for four years partly because the ceremony would reinforce the

prejudices of those convinced he was "some sort of poodle", says Sir

David Manning, Britain's Ambassador in Washington.

The Prime Minister's 1,351-day delay in collecting the medal from

President Bush has long been a source of puzzlement in both Washington

and London. Downing Street insists that it is still being designed.

But as Mr Blair prepares to leave office, Sir David told The Times in

a rare interview that the Prime Minister "always had inhibitions" about

being handed a medal that was awarded shortly after the invasion of Iraq

at his triumphant address to both houses of Congress in July 2003.

Sir David - who was Downing Street's chief foreign policy adviser in

the run-up to the invasion - seeks to tackle perceptions about Britain's

relationship with America and that between the two leaders, whose place

in history is likely to be defined by the Iraq war.

"For those who are convinced that the Prime Minister is . . . some

sort of poodle, it does not matter what he does," says Sir David, who

will finish his four-year stint as Ambassador this autumn. "You reach

the point where if he had collected the medal, people would say that

proves their point. But it's a much better - a much more complicated

relationship - it's a two-way street."

Speaking from his Lutyens-designed residence in Washington, he says

the relationship between the two countries has not "become more unequal"

in recent years, because since the Second World War, America has been

the world's pre-eminent power" while Britain has had to learn to

"operate as a medium-sized power".

But he accepts that anti-American sentiments have been fuelled by

events that serve to undermine the sense of shared values between Europe

and the US. Sir David says when he arrived in Washington, "my impression

was that the politics was still very much the politics of 9/11".

But that changed with November's midterm elections when the Democrats

were swept back into power on Capitol Hill. "What we have now is a very

different Congress and a very different political debate - not

everything is about national security and Iraq. But that changed with November's midterm elections when the Democrats

were swept back into power on Capitol Hill. "What we have now is a very

different Congress and a very different political debate - not

everything is about national security and Iraq.

Of course in 2008, Iraq will be a central issue but politics is back

in America after being anaesthetised for a four or five-year period.

"I think that is healthy and a good thing that will play into

perceptions of the US overseas. The debate they are going to have will

be much more recognisable to European public opinion." He is troubled by

the rise of anti-American attitudes, saying it "would just be folly to

turn away from the US" and try to tackle global challenges alone.

"It does scare me and I hope that it will correct itself the further

we get away from post-9/11 politics and the co-operative multilateral

relationship reasserts itself." Such comments might be interpreted as

suggesting that Britain's ability to wield influence in Washington has

been hobbled.

That perception appeared to have been confirmed earlier this year by

Kendall Myers, a US State department official, who described the

relationship with Britain as utterly one-sided where Mr Blair's views

are routinely ignored.

But Sir David insists that the Prime Minister, because of Britain's

long-term interests, would "have had to work closely with whoever was in

power" - as he did with President Clinton.

Indeed, the Ambassador says there have been many occasions when

Britain has made plain its differences with the Bush Administration. He

cites America's detention of terror suspects at Guantanamo Bay and its

scepticism about scientific evidence for climate change, as well as Mr

Blair's commitment to a Middle East peace settlement and his

multilateralist view of the world.

"What is crucial in the relationship is that when we take different

positions it does not affect overall co-operation," he says. "There has

been a subtler process of engagement across a range of issues - how do

you handle proliferation, particularly that of Iran? How do you handle

climate change?

"These are not necessarily easy issues in this country but, by having

the debate I have no doubt we have influenced them." He suggests that

what Condoleezza Rice, the US Secretary of State, is now doing with the

latest Middle East peace initiative involving Arab countries "is very

much what we would be urging them to do", while there has also been a

"slight shift" in Mr Bush's attitude on climate change "where we have

had influence".

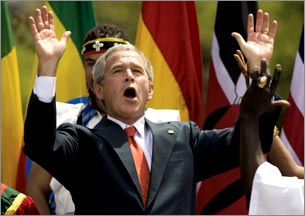

The "cartoon-like interpretation of Bush in some quarters" clearly

irritates Sir David, who says the image of the President as a

unilateralist who ignores other countries is based primarily on the

experience of Iraq. This, he says, ignores more recent efforts by the

Administration to work closely with the UN and Europe, as well as China

and Russia, on tackling nuclear threats posed by North Korea and Iran.

A small, bespectacled and softly spoken man, Sir David is held in

huge esteem within Washington where - both as Mr Blair's foreign policy

adviser and as ambassador - he is probably the best-informed witness of

the two leaders' relationship.

For critics of the Prime Minister, this appeared to be summed up by

last year's embarrassing "Yo, Blair" moment at the G8 summit when

neither of them realised a microphone had been left on as the President

appeared to dismiss out of hand Mr Blair's offers of help on the Lebanon

crisis.

Sir David rejects such interpretations, saying: "The President has

own joky way with people . . . he is naturally ebullient. I think it was

like a Texan saying 'Howdy'."

So what is it really like when they meet in private? "It's frank,

very plain," he says. "Both of them know what they want to emphasise and

where they want the conversation to go. They have become comfortable

about dealing with the difficult things as well as the easy things."

www.timesonline.co.uk |