Contemporary Sinhala novel and its future

“New generation of novelists should expand the vistas

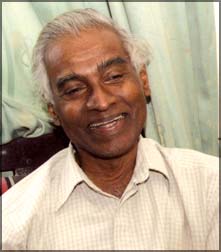

of expressive idiom in Sinhala” Prof. K. N. O. DharmadasA:

by Indeewara THILAKARATHNE

In an interview with Sunday Observer, Prof. K.N.O. Dharmadasa

expresses his candid views on the state of contemporary Sinhala novel

and the important role of novelist as creator of expressive idiom in

language.

Q: In the context of globalisation, the Sinhala novel is at

cross-roads. Contemporary writers are increasingly looking for

structures and are greatly influenced by post modern writers. How do you

perceive the contemporary Sinhala novel? Q: In the context of globalisation, the Sinhala novel is at

cross-roads. Contemporary writers are increasingly looking for

structures and are greatly influenced by post modern writers. How do you

perceive the contemporary Sinhala novel?

A: We have to place the Sinhala novel in a historical context.

Sinhala novel was born hundred years ago. Starting from the early novels

by Albert de Silva and Piyadasa Sirisena, the Sinhala novel has been for

quite sometime, in the shadow of our (Sinhalese) ancient classical

literature.

Early Sinhalese novelists such as Albert de Silva and Piyadasa

Sirisena derived inspiration from classical writing. Their purpose was

to advise society and to give a religious message with didactic content

through a prose narration. Very often they depict even the contemporary

events in such a way that in the end goodwill triumphs over the evil.

In a way these authors had the notion that literature has to be

socially relevant in a correct way. Why I am highlighting this point is

that today, social relevance does not mean what earlier novelists meant

by it.

I think that the early novelist thought that they had a duty by the

society, by highlighting the triumph of good over evil. They thought

that was the social responsibility of a good novelist, purpose of the

novel and that a good writer has the welfare of society in mind.

He has to portray society in such a way that the morals, what you

call ‘Saradharma’ (ideals) and norms of society are upheld and they are

not violated. Today the writers do not take that point of view into

consideration.

Their attitude is: ‘we are also depicting society but we depict good

as well as evil’ and very often it is the evil that is highlighted.

For example, see what is depicted in television. We have twelve odd

television channels and every hour teledramas being telecast. Most of

the teledramas depict unsavoury aspects of life and I feel some of them

are unrealistic; families are broken, husbands have love affairs with

women other than their wives and wives have affairs with men other than

their husbands.

All kinds of evil aspects are highlighted. The prime time television

very often has this nature of message which I think, is not good for the

society.

Although they may reflect some kind of reality, it is not the reality

as it is apparent to us. This is why we admire writers like Albert

Silva, Piyadasa Sirisena, W. A. Silva and even Martin Wickramasinghe.

Although Martin Wickramasinghe wrote realistic novels, he did not depict

these kinds of affairs. There was a kind of restrain.

A writer operates in society. He or she has a power. How does a

writer use that power? Is he or she using that power for the good of the

society or for the disruption of society? We did not think in these

lines in our youth but now in maturity, I believe that the art produced

in a society has to be for the well-being of the society while

maintaining the balance and not be disruptive. Even in other aspects

such as economic, social balance has to be sustained and promoted.

That is a kind of task expected from a person who wields power,

especially of a writer who wields real power. Artists, theatre

personalities, filmmakers have to think of their impact of the work on

society. We were nurtured by a tradition. The writers Albert Silva,

Piyadasa Sirisena and Martin Wickramasinghe were rather conservative and

wanted to maintain the social balance.

During the middle of the last century, a revolutionary movement was

born which looked at the society from a different perspective. I refer

to early novels by Gunadasa Amerasekara. In the novels Yali Upannemi and

Depa Noladdo, Gunadasa Amerasekara deals with sex in a revolutionary way

which never before found expression in the Sinhala novel. Yali Upannemi

was an extremely revolutionary novel. In our young days we admired the

writer for bringing this subject to discussion and it was a

controversial novel.

Looking back even the writer Gunadasa Amerasekara was critical of the

novel, saying that he was not reflecting social reality and he got

material from English novelists like D. H. Lawrence and French writers

for his work.

These western writers tried to depict society in Europe and not in

Sri Lanka. For example, the plot of Yali Upannemi depicts a sex life of

a young man. Some of these situations he tries to recreate are not real

and they are not really found in Sri Lankan society. Gunadsa Amerasekara

was critical of these novels and he did not agree with the sentiments

expressed in them.

Q: What is the pivotal role that the Peradeniya School played in the

formation of the Sinhala novel?

A: So there was a revolution which Gunadasa Amerasekara attributed to

the Peradeniya School of Literature. Gunadasa Amerasekara, Siri

Gunasinghe and Prof. Ediriweera Sarachchandra spearheaded the movement.

In none of his works, Prof. Sarachchandra did openly discuss sex. But,

sometimes, he gave subtle suggestions. I wonder whether one can put the

blame on Prof. Sarachchandra when it was stated that the Peradeniya

School brought out these novels. In his criticism of the novel “Modern

Sinhalese Fiction “(1943) and in the ‘Sinhala Navakatawa’ (The Sinhalese

Novel) (1950), he criticised Piyadasa Sirisena for being didactic

writer, moralist, rejecting modernity and being conservative. That

criticism may be appropriate at that time.

Because we were trying to look forward and forge ahead and develop

our new literary genre. In that context, Prof. Sarachchandra was

correct. I wonder whether he encouraged kind of situations that were

written about in Yali Upannemi and Depa Noladdo. I recollect that he

wrote a review on Yali Upannemi and praised it as a good piece of

literature. Apart from that I do not think he went on nurturing this

type of writing. If he did so, he himself could have written this type

of novels. I think he adhered to a very traditional way of looking at

life. He was very careful not to cross certain lines which he drew

himself.

Simon Navagattegama who came after the Peradeniya School was a unique

figure. He had his own perspective of looking at society. From Sansara

Arana, Dadayakkaraya to Sapekshani, the way he deals with sex, I feel,

is artificial. He depicts sexual aspect of life as mystique and

overdoing it. Sex is a part of life and people have other concerns.

Q: Over the years, Sinhalese novel evolved a form which is unique to

it. How do you define this coming of age of the Sinhalese novel?

A: For instance, Gunadasa Amerasekara, in his latest book ‘Nosevuna

Kadapatha’, deals with not only a novel but also with the literary

landscape. What he is trying to say is that there are certain realities

of the society which the novelist should reflect. Why aren’t we looking

for that mirror which reflects social realities beyond appearances.

After Martin Wickramasinghe’s Gamperaliya and Viragaya, a new generation

of novelists emerged like K. Jayatilake. As far as the realistic

movement is concerned, K. Jayatilake is very important. He was depicting

the social transformation in the village in the 20th century in Sri

Lanka. K. Jayatilake and A. V. Suraweera wanted to look beyond the

social facade and look at social forces at work. For instance, how the

older village hierarchy, the people of high caste and people of high

standards are loosing their grip and the middle class comes up; the

newly emerged business class, schoolteachers and Government servants who

were asserting their power and the old system was breaking down. Though

Martin Wickramasinghe did the same, these new writers did it more

intimately.

In K. Jayatilaka’s Charita Thunak (Three Characters), he depicts

three characters; Elder brother and two younger brothers. One of them

becomes a schoolteacher and asserts his identity and economic power in a

very strong way because he is educated. He also tries to amass wealth

and tries to become a powerful figure in society. Third brother who is a

school dropout wasted his life drinking and loitering. The eldest

brother, who is the narrator, looks at this transformation from a

detached point of view. Social transformation is looked from the eyes of

one person. In a way depicting this transformation, Jayatilake is

superior to Wickramasinghe.

Wickramasinghe’s depicting of transformation is too detached to be

felt in the heart. This is where Gunadasa Amerasekara is stronger than

even Jayatilake. The way he deals with social transformation is very

intimate. He uses very, evocative, poetic language and emotion-laden

language and the novel use of folk idiom. In the use of spoken idiom to

depict social situations, characters and their emotions, Gunadasa

Amerasekara stands as one of the greatest literary figures, Sri Lanka

had produced in the 20th century.

I find when I read new novelists’ work, they are more concerned about

structures and how they are trying to relate to Western novel and

post-modernistic structures rather than intimate depiction of their

subject.

If they spend half of the time on Sinhala language and its

expressiveness and how one can use it to depict what they want to

depict. That is where they failed. No Sinhala reader would feel these

novels are about them and depiction of society they live in. They do not

see expressiveness which is deeply embedded in our idiom. The older

generation of novelists advise new writers to read all the classics

starting from Amawatura and study the folk idiom around. A novelist is

not only a* *man who derives from idiom but also a creator of idiom. For

instance, Gunadasa Amerasekara is a creator of idiom and in his works

like Jeevana Suwanda, he has extended the frontiers of language. Three

novels selected for Swarna Pustaka Award were serious novels. As a

person who enjoyed good literature and who wish our literature to

flourish and language to be more powerful, I would invite new writers to

extend the vistas of our expressive idiom of Sinhala and to make it more

subtle to depict emotions and situations in a novel manner. Novelist is

a thinker with a penetrative vision who tries to see social forces at

work, psychological forces at work and realities brought about by

globalisation and youth issues. The new generation should go beyond

expressive idiom used by Martin Wickramasinghe or Gunadasa Amerasekara

and it is where the future of the Sinhalese novel should lie. |