|

French Renaissance literature:

Classicism and seventeenth century French literature

The 17th century produced the great academies and coteries of French

literature. The elegant, controlled aesthetic of French classicism was

the hallmark of the age. The great writers vary enormously in their

attitudes and interests but share a style that is lucid, polished, and

restrained. The 17th century produced the great academies and coteries of French

literature. The elegant, controlled aesthetic of French classicism was

the hallmark of the age. The great writers vary enormously in their

attitudes and interests but share a style that is lucid, polished, and

restrained.

They were, as a group, chiefly concerned with observing the

subtleties of human behaviour. Their works display qualities that have

become permanently identified with the best French writing: wit,

sophistication, imagination, and delight in debate.

Pierre Corneille

Corneille (June 6, 1606 – October 1, 1684) was a French tragedian who

was one of the three great seventeenth century French dramatists, along

with Molière and Racine.

|

|

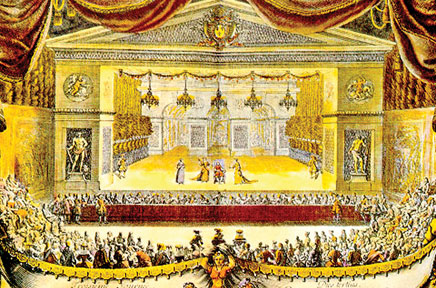

17th century theatre |

He has been called “the founder of French tragedy” and produced plays

for nearly 40 years. In the sixteenth century, the French Renaissance

developed alongside the continuation of medieval theater and especially

the morality play.

While ancient theater was re-introduced during the sixteenth century,

it was not until the seventeenth century and the work of Corneille and

Racine that the ancient tragedies would serve as models for French

dramatists. They would go back beyond Christian models to Greek

antiquity to re-introduce the ideas and characters of that

pre-Christian, Hellenic world.

The works of Corneille represent most fully the ideal of French

so-called "classical" tragedy. The laws to which this type of tragedy

sought to conform were not so much truth to nature as the principles

which the critics had derived from a somewhat inadequate interpretation

of Aristotle and of the practise of the Greek tragedians.

These principles concentrated the interest of the play upon a single

central situation, in order to emphasize which, subordinate characters

and complicating under-plots were avoided as much as possible. There was

little or no action upon the stage, and the events of the plot were

narrated by messengers, or by the main characters in conversation

with confidantes. By 1629 the French theater was moving away from the

exuberant baroque style of the early 17th century toward a dramaturgy

based on the theatrical precepts of Aristotle and his commentators since

the Renaissance.

The general rules included the famous principle of "three unities"

(time, place, and action), according to which a play must present a

single coherent story, taking place within one day in a single palace or

at most a single city.

They also included the principles of theatrical verisimilitude (the

events presented must be believable) and of bienséance (standards of

"good taste" must be followed to avoid shocking the audience). These

three major precepts structured the great classical theater of the

following decades in France.

Le Cid

The most famous of Corneille’s plays was the tragicomedy ‘Le Cid’,

first produced in Paris, probably late in November, 1636. The famous

soldier, Diègue, had served King Fernand of Castile faithfully and well.

In his old age he was rewarded with the coveted position of tutor to the

young Prince.

Since Gomez, Count of Gormaz, although considerably younger, had been

scarcely less conspicuous for personal bravery and crafty generalship,

he had believed that he would be chosen for this mark of honor. In his

bitter disappointment he not only refuses to sanction the marriage of

Diègue's son, Roderick, to his daughter, Chimène, but offered deadly

insult to Diègue by a blow to the face.

Since Diègue was too infirm to wield a sword in defense of his honor,

it fell to Roderick's lot to avenge his father in a duel from which he

emerged victorious. Knowing that by killing Chimène's father, he had

sacrificed all hope of winning her, Roderick begged the girl to kill

him.

Although filial love and duty had impelled her to demand vengeance

from the King, she could not kill the man she loved for obeying the

dictates of honor. Meanwhile, since Roderick had made himself subject to

arrest by a duel which the King had forbidden, Diègue persuaded his son

secretly to head a band of trusty followers and to ambush the Moors who

even at the moment were about to attempt a surprise attack.

So well did Roderick acquit himself that even the two Sultans,

captives of his prowess, acclaimed him Cid, the highest honor they could

conceive. After this additional proof of loyalty and bravery, the King

could do no less than forgive his young subject.

Chimène, however, still insisted on revenge. At length the King

permitted her to name her other suitor, Sancho, to avenge her father in

single combat with Roderick, naming her hand as the winner's reward.

Roderick's assurance that he would offer no resistance to death at

the hands of her chosen champion, finally forced from Chimène the

reluctant admission that only a sense of filial duty had impelled her to

insist on vengeance. Roderick's assurance that he would offer no resistance to death at

the hands of her chosen champion, finally forced from Chimène the

reluctant admission that only a sense of filial duty had impelled her to

insist on vengeance.

She begged him to rescue her from a hateful marriage. When the duel

was over and Sancho appeared, sword in hand, Chimène jumped to the

conclusion that Roderick was dead.

Falling on her knees before the King, she begged that she be released

from the promise of marriage to enter a convent, bestowing her fortune

on Sancho in reparation.

As it turned out, Sancho had merely come to report that he was alive

because Roderick had generously refused to take the life of one who

loved Chimène. Thus both honor and love were satisfied.

Le Cid was one of the greatest theatrical successes of the 17th

century. And although its success was marred by a literary quarrel in

which lesser authors attacked its transgressions against the literary

rules, it marked Corneille as a major dramatist and opened the most

important epoch of his career.

During this period Corneille showed great pride in his literary

accomplishments but continued to practice law in Rouen, Normandy and

remained very much a bourgeois provincial who had made good.

He was both resentful of, and deferential to, the literary

"authorities" who attacked his play. When the newly founded French

Academy decided against him, he was genuinely discouraged and apparently

abandoned the theater for some time.

Glory, Heroism and Moral Conflict

Overcoming his discouragement, Corneille wrote the successful tragedy

Horace (1640), which was soon followed by Cinna (1640) and Polyeucte

(1642).

In these tragedies he continued to explore the concepts of glory,

heroism, and moral conflict. Based on an incident from early Roman

history, Horace depicts a young man who with his brothers, the Horatii,

is obliged to defend Rome in combat against three brothers (the Curatii)

from an enemy town.

Horace's wife, however, is a sister of the Curatii, and his own

sister is engaged to one of them.

In Cinna a conspirator hesitates between his fidelity to the state

and the desire for vengeance of the woman he loves; and the Roman

emperor Auguste, who discovers the conspiracy, must choose between

vengeance or clemency for the conspirators. inna, we are presented with

a situation that, for all intents and purposes, begins on a path to

tragedy.

As the suspense builds and true battle-lines are drawn, we, familiar

with tragic convention, expect deaths, retribution, and drawn-out

laments over foolishly squandered lives, but Corneille does not deliver

what we expect.

At ‘Cinna’s end there is no tragedy at all, rather, we are given the

happiest ending possible, with not one person dying, or even suffering

punishment, and the benevolent Augustus surrounding by his smiling,

grateful, friends.

He even announces the wedding of Cinna and Emilia. While this play

begins in a way that leads us to expect tragedy, it certainly does not

end in a tragic way, so it cannot be, in the Aristotelian sense or any

other, regarded as a proper tragedy.

In Polyeucte the hero is converted to Christianity during the Roman

persecution of the Christians. He openly attacks the pagan religion, and

thus he, his wife, his father-in-law (the Roman governor), and a noble

Roman envoy must reconcile personal feelings and religious or political

duty.

The drama is set in Armenia during a time when Christians were

persecuted there under the Roman Empire. Polyeucte, an Armenian

nobleman, converts to Christianity to the great despair of his wife,

Pauline, and of his father-in-law, Felix.

Despite them, Polyeucte becomes a martyr, causing Pauline and Felix

to finally convert as well.

There is also a romantic subplot: the Roman Severus is in love with

Pauline and hopes she will be his after the conversion of Polyeucte.

However, she chooses to stay at the side of her husband. Before dying,

Polyeucte entrusts Severus with Pauline.

This tragedy departs radically from the dramatist's named sources,

more so than in any other of his works. It is argued here that the plot

is altered in order to avoid any potentially subversive readings.

|

|

Le Menteur by Corneille |

There is an obvious political agenda - that the monarch is not

criticized at any point, yet one factor that has been overlooked may be

a desire to neutralize the suggestion of homo eroticism.

Thus, the play represents an apologia for Christian marriage and

intimate relations between the sexes. This manipulation amounts to the

portrayal of a heterosexual hero, far removed from a virgin-martyr

stereotype, and from the saint's legend as presented in standard

narratives.

Overall, Corneille's intense focus on human will, the will striving

for freedom, and the fashioning of one's own destiny distinguishes his

tragedies from classical Greek dramas, in which humans are depicted as

helpless victims of fate.

Critical reception

Critics have praised Corneille's plays for their great diversity,

brilliant versification, and complexity of plot and situation.

Scholars have also applauded his liberation of tragedy from the

confinement and artificiality of neoclassical strictures. Much critical

discussion of Corneille's work focuses on his relationship with his

contemporary and rival, the playwright Jean Racine.

Many scholars compare the objectives and accomplishments of Corneille

with those of Racine, often to Racine's advantage.

Although the decline of Corneille's reputation, begun in his own

lifetime, continued throughout the eighteenth century, the next century

saw a reappraisal of his place in literary history, and today he is

situated in the front rank of French dramatists.

Le Cid was so different from Corneille's earlier dramas that it

hardly seems the work of the same hand.

|