|

Human-like walking began nearly 4 million

years ago

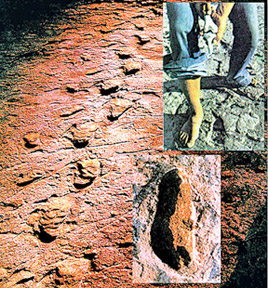

Scientists at the University of Liverpool have found that ancient

footprints in Laetoli, Tanzania, show that human-like features of the

feet and gait existed almost two million years earlier than previously

thought.

Many

earlier studies have suggested that the characteristics of the human

foot, such as the ability to push off the ground with the big toe, and a

fully upright bipedal gait, emerged in early Homo, approximately 1.9

million years-ago. Many

earlier studies have suggested that the characteristics of the human

foot, such as the ability to push off the ground with the big toe, and a

fully upright bipedal gait, emerged in early Homo, approximately 1.9

million years-ago.

Liverpool researchers, however, in collaboration with scientists at

the University of Manchester and Bournemouth University, have now shown

that footprints of a human ancestor dating back 3.7 million years ago,

show features of the foot with more similarities to the gait of modern

humans than with the type of bipedal walking used by chimpanzees,

orangutans and gorillas.

The footprint site of Laetoli contains the earliest known trail made

by human ancestors and includes 11 individual prints in good condition.

Previous studies have been primarily based on single prints and have

therefore been liable to misinterpreting artificial features, such as

erosion and other environmental factors, as reflecting genuine features

of the footprint. This has resulted in many years of debate over the

exact characteristics of gait in early human ancestors.

The team used a new statistical technique, based on methods employed

in functional brain imaging, to obtain a three-dimensional average of

the 11 intact prints in the Laetoli trail. This was then compared to

data from studies of footprint formation and under-foot pressures

generated from walking in modern humans and other living great apes.

Computer simulation was used to predict the footprints that would

have been formed by different types of gaits in the likely printmaker, a

species called Australopithecus afarensis.

Professor Robin Crompton, from the University of Liverpool's

Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease, said: "It was previously

thought that Australopithecus afarensis walked in a crouched posture,

and on the side of the foot, pushing off the ground with the middle part

of the foot, as today's great apes do.

"We

found, however, that the Laetoli prints represented a type of bipedal

walking that was fully upright and driven by the front of the foot,

particularly the big toe, much like humans today, and quite different to

bipedal walking of chimpanzees and other apes. "We

found, however, that the Laetoli prints represented a type of bipedal

walking that was fully upright and driven by the front of the foot,

particularly the big toe, much like humans today, and quite different to

bipedal walking of chimpanzees and other apes.

"Quite remarkably, we found that some healthy humans produce

footprints that are more like those of other apes than the Laetoli

prints. The foot function represented by the prints is therefore most

likely to be similar to patterns seen in modern-humans.This is important

because the development of the features of human foot function helped

our ancestors to expand further out of Africa.

"Our work demonstrates that many of these features evolved nearly

four million years ago in a species that most consider to be partially

tree-dwelling.

‘These findings show support for a previous study at Liverpool that

showed upright bipedal walking originally evolved in a tree-living

ancestor of living great apes and humans

"The Laetoli footprint trail is a snapshot of how early human

ancestors used their feet 3.7 million years ago. By using a new

technique for averaging footprints, foot pressure information from

modern great apes, and computer simulation of walking in the proposed

Laetoli printmaker, we can see that the evidence points to surprisingly

modern foot function very early on in the human lineage."

Courtesy: Science Daily

|