Stamping out the HIV stigma

By Lionel WIJESIRI

|

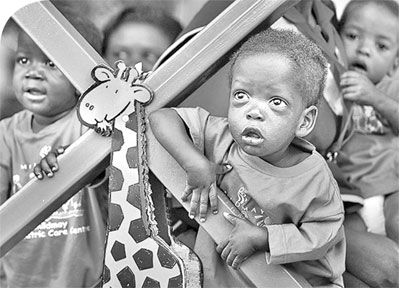

HIV/AIDS has affected many children in Africa

|

Consultant Specialist Dr. P. Weerasinghe revealed recently that as at

March 31, 2012 there were 775 AIDS patients and 1,503 individuals who

had contracted HIV in Sri Lanka. He added that according to the figures

available, there are more than 3,000 people affected by HIV in the

island. Consultant Specialist Dr. P. Weerasinghe revealed recently that as at

March 31, 2012 there were 775 AIDS patients and 1,503 individuals who

had contracted HIV in Sri Lanka. He added that according to the figures

available, there are more than 3,000 people affected by HIV in the

island.

Sri Lanka is considered a low prevalence country in the South Asian

region with less than 0.1 percent of the general population infected

with HIV. According to the National STD/AIDS Control Program, the HIV

prevalence rate has remained less than one percent even among

most-at-risk populations such as female sex workers.

Still, Sri Lanka also has risk factors which could potentially

increase the rates of HIV transmission. Among them are:

* Migration for employment,

* Increasing number of sex workers. It is estimated that there are

40,000 women engaged in commercial sex today,

* Increasing number of sexually active youth,

* Low levels of knowledge about HIV,

* Booming tourism.

There are a number of factors which act as barriers to public action.

Among them, stigma remains the most important one. It is the main reason

too many people are afraid to see a doctor to determine whether they

have the disease, or to seek treatment if they do.

It helps make AIDS the silent killer, because people fear the social

disgrace of speaking about it, or taking easily available precautions.

Stigma is the chief reason the AIDS epidemic continues to devastate

societies around the world.

A physician once told me, “If you had an opportunity to talk to a few

patients with HIV, you will understand that their overriding concern is

not the infection itself, but the way other people will treat them

should they find out about their condition”.

Death sentence

Even now, 30 years after the virus was identified and despite the

availability of potent drugs that mean a positive diagnosis is no longer

an automatic death sentence, HIV/AIDS remains a disease shrouded in

secrecy because of the persistent stigma attached to it. People who are

HIV positive can be anywhere in our community and still at risk of

discrimination, based on misunderstanding and half-truths. HIV attracts

ignorant infamy and hostility like few other diseases.

Back in the eighties, there was rampant speculation about the

infection, because scientists were baffled by it. The legislation and

guidance originating from that era reflects this huge uncertainty.

However, HIV is now one of the most scrutinised of all viruses, its

transmission, spread, management, treatment and prevention understood

like no other. This knowledge has rendered many of the restrictions put

in place 20 or more years ago, based on what was known then, massively

out of date.

Stigma not only makes it more difficult for people trying to come to

terms with HIV and manage their illness on a personal level, it also

interferes with attempts to fight the AIDS epidemic as a whole. On a

national level, the stigma associated with HIV can deter governments

from taking fast, effective action against the epidemic, while on a

personal level it can make people reluctant to access HIV testing,

treatment and care.

What is the reason for this stigma? Fear of infection coupled with

negative, value-based assumptions about people who are infected leads to

high levels of stigma surrounding HIV and AIDS.

Factors that contribute to HIV/AIDS-related stigma include:

* HIV infection is associated with behaviour (such as homosexuality,

drug addiction, prostitution or promiscuity) that are already

stigmatised in many societies.

* Most people become infected with HIV through sex, which often carries

a social stigma.

* There is a lot of inaccurate information about how HIV is transmitted,

creating irrational behaviour and misconceptions of personal risk.

* HIV infection is often thought to be the result of personal

irresponsibility.

* Religious or moral beliefs lead some people to believe that being

infected with HIV is the result of moral fault that deserves to be

punished.

* The effects of therapy on people’s physical appearance can result in

forced disclosure and discrimination based on appearance.

Different contexts

|

An AIDS patient |

In 2003, when launching a major campaign to scale up treatment in the

developing world, the World Health Organization (WHO) said: “As HIV/AIDS

becomes a disease that can be both prevented and treated, attitudes will

change, and denial, stigma and discrimination will rapidly be reduced.”

It is difficult to assess the accuracy of this statement as levels of

stigma are hard to measure and a number of small-scale studies has shown

that the relationship between increased access to HIV treatment and a

reduction in stigma is not always clear.

The fact that stigma remains in developed countries such as USA,

where treatment has been widely available, also indicates that the

relationship between HIV treatment and stigma is not straightforward. An

estimated 27 percent of Americans would prefer not to work closely with

a woman living with HIV. Moreover, preliminary results found that 17

percent of respondents living with HIV in the UK had been denied health

care and that verbal harassment or assault had been experienced by 21

percent of respondents.

I asked a young educated woman what she thinks about a colleague

living with HIV. “Because it is about sex, I think she got it because

she has been loose…she is not anything better than a prostitute.”

This woman’s experience reveals the multi-layered nature of stigma.

Within her quote she reveals being stigmatised, but perhaps unknowingly

accepting of the stigma against infected sex workers.

In the workplace, people living with HIV may suffer stigma from their

co-workers and employers, such as social isolation and ridicule, or

experience discriminatory practices such as termination or refusal of

employment. Fear of an employer’s reaction can cause anxiety in a person

living with HIV.

Community

A community’s reaction to somebody living with HIV can have a huge

effect on that person’s life. If the reaction is hostile a person may be

discriminated against and may be forced to leave their home, or change

their daily activities such as shopping, socialising or schooling.

Community-level stigma and discrimination can manifest as rejection

and verbal and physical abuse. It has even extended to murder. AIDS

related murders have been reported in countries as diverse as Brazil,

Colombia, Ethiopia, India, South Africa and Thailand. It is therefore

not surprising that 79 percent of people living with HIV who

participated in a global study, feared social discrimination following

their status disclosure.

Family

In developing countries, families are the primary caregivers when

somebody falls ill. There is clear evidence that families play an

important role in providing support and care for people living with HIV

and AIDS. However, not all family responses are supportive. HIV positive

members of the family can find themselves stigmatised and discriminated

against within the home.

Progress

So how can progress be made in overcoming this stigma and

discrimination? How can we change people's attitudes to AIDS? A certain

amount can be achieved through the legal process.

In some countries people living with HIV lack knowledge of their

rights in society. In this case, education is needed so they can

challenge the discrimination, stigma and denial that they encounter.

Institutional and other monitoring mechanisms can enforce the rights of

people with HIV and provide powerful means of mitigating the worst

effects of discrimination and stigma.

However, no policy or law can combat HIV/AIDS related discrimination

on its own. Stigma and discrimination will continue to exist as long as

societies have a poor understanding of HIV and AIDS and the pain and

suffering caused by negative attitudes and discriminatory practices.

The fear and prejudice that lie at the core of the HIV/AIDS-related

discrimination need to be tackled at the community and national levels

with AIDS education playing a crucial role.

A more enabling environment needs to be created to increase the

visibility of people with HIV/AIDS as a ‘normal’ part of any society.

The presence of treatment can make this task easier; where there is

the opportunity to live a fulfilling and long life with HIV, people are

less afraid of AIDS; they are more willing to be tested for HIV, to

disclose their status, and seek care if necessary.

The task is to confront the fear-based messages and biased social

attitudes, to reduce the discrimination and stigma of people living with

HIV and AIDS.

|