|

A discussion on Parvathi Solomons Arasanayagam’s

Contrapuntal:

Narrative landscapes created from memories and reflections

By Dilshan BOANGE

|

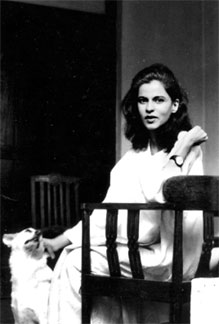

Parvathi Solomons Arasanayagam |

Contrapuntal by its definition means ‘polyphony’ which denotes having

many voices or tones. From a point of musicology the word polyphony

speaks of two or more melodies independent of each other coexisting

harmoniously in a single composition. Parvathi Solomons Arasanayagam’s

collection of fiction titled Contrapuntal and other stories speaks of

persons who would generally be at the fringes of society and those who

from a more empowered stratum, would be able to speak of them and make

an account of their existence.

This article looks at the central title piece of the book

Contrapuntal which runs the length of a novelette coursing the reader

through 52 pages of solid prose writing which does not in any way seem

pretentious of the world of experience sought to be conveyed to the

reader from the rather subjectively observed narrator.

The narrative contains more than one stream of focus and fuses

through tonally harmonised prose different aspects of the narrator’s

world of experience which never the less finds cohesion through subtle

links and interweaving. What Parvathi offers the reader is not a work

which drives the reader on a race of excitement and thrills. It is more

a call to become meditative and empathise with the central character

Sonali and the world she observes very sensitively. The narrative gives

much detail of the wayside sights and people that fill the picture that

is Kandy, but not from the central mainstream image of its cultural

grandeur and abundant heritage of hallowed antiquities. The narrative contains more than one stream of focus and fuses

through tonally harmonised prose different aspects of the narrator’s

world of experience which never the less finds cohesion through subtle

links and interweaving. What Parvathi offers the reader is not a work

which drives the reader on a race of excitement and thrills. It is more

a call to become meditative and empathise with the central character

Sonali and the world she observes very sensitively. The narrative gives

much detail of the wayside sights and people that fill the picture that

is Kandy, but not from the central mainstream image of its cultural

grandeur and abundant heritage of hallowed antiquities.

What Parvathi offers her readers is what goes unnoticed or lays

hidden from the eyes of the visitor or casual passerby. It is an account

of an observer whose keen eye and receptive senses collects and ponders

on images and experiences that weave the text as a storehouse of

emotions and information that run the common course of a readable story.

Sociological values

The story captures a slice of life of the less privileged, whose life

is interpretable through the labour they perform, and in certain cases

the hopes they carry of becoming something more than their given station

in life. The characters of the servant Bisso Menike, the washerwoman

Ukku amma, and Peter, the boy who helps Sonali’s parents with work in

the house and acts as a trusted escort to the protagonist and her sister

show portraits of the underprivileged within the context of society and

the conditions that shape them.

Parvathi’s narrative also gives a perspective on the ethnological

layering that underscores the plight of some segments in society such as

those who lived on embankments of rivers and were very obviously not

part of the ‘majorities’ in Kandy, the prime example being the

bastardised progeny of westerners and local women.

The daily ways and means of labourers and how they manage to

momentarily escape the great exhaustions their bodies and minds are

battered with by gulping down toddy by the side of wayside food kiosks,

in the safety of shadows in the night time are narrated with details

that paint a very potent and vivid picture in the mind of the reader.

The varieties of food and the kinds of recreation people indulge in

like the Kafferinjha and baila songs sung to the sound of violin music

amongst Peter’s families, show the authoress has been sensitive to

capture these threading existent in that social milieu. And while the

protagonist Sonali were not amongst the cream of society and had their

share of financial concerns they were certainly better off than the

orphans of ‘cottage house’ about whom the authoress gives glimpses for

the reader to understand the strata which formed the social fabric.

Perhaps these were what the writer documented in her own observations

being transferred to the world of the protagonist, or perhaps Parvathi

has improvised what she encountered to make them more intriguing to the

reader. However, it may be treated as very much a glimpse into a world

that is not far removed from conceivable realities in landscapes found

in Sri Lanka. Although the genre of the work would be creative writing

the verisimilitude in this work may very well offer ground for scholarly

analysis from vantages of sociological investigations.

Document of topography

The scenic beauties of Kandy and the lush Kandyan hill country flows

out mesmeric and mystically to the reader through the well crafted

prose. Anyone who has travelled to Kandy and appreciates the climatic

appeal it has to an exhausted body will surely feel an immediate lull

descend as the calmness that is Kandy (compared to Colombo) comes alive

with the words the authoress puts together to weave images of the

topography that has shaped her being. Watapuluwa, Sirimalwatte,

Mawilmada, are locales the writer mentions along this journey of

creating a topological narrative which would be easily relatable to a

reader who would be familiar with these places in Kandy.

What seems rather true to the spirit of recollection is how the

narrative gives an account of the areas in and around Kandy is not as if

they were places revisited by an outsider but relived in the mind of the

inhabitant who is distanced from the original observations by chronology

and not memory.

Describing life from a point of topography gives a firm grounding to

establish time and space of a story. Being firmly rooted in the mode of

realist fiction Parvathi gives the reader the documented Kandy of her

observations, capturing not only the images of the habitations of the

people of more or less in proximity to Sonali’s stratum but also of the

marginalised.

The geography of how the Mahaweli river may mark a locale’s character

by being within seeing range of a bus that meanders along the hilly road

are details the narrative brings to the attention of the reader

sometimes as an authorial tone and sometimes blending with the

observational input through the protagonist.

The cruxes of the story

What strikes as rather notable in this piece of fiction is that the

centrality of what seems the primary ground on which the narrative

builds itself may be disputed as not being the only foundation for the

story to be told. The protagonist Sonali’s experience of being part of a

dance class and the efforts put in by the whole class and the dance

teachers in working towards the much awaited concert becomes key to

understand the purpose of the narrative which comes as a journey into

the interior of the protagonist whose contemplations become a window to

the reader to look both inwards at Sonali and the world outside her,

through her vision’s scope.

The beginning of the narrative is an account from the first person of

how (presumably) the authoress reviews part of her childhood. The start

is about a train journey to Colombo to visit the grandparents of whom

the reader is made to know sufficient details to develop a clear picture

of how the familial environment would have been.

The switch in focus to the character of Sonali begins as the

authorial voice describes her waiting for the bus at a night time. From

there onwards one cannot help but feel the idea of travel and journeying

is meant to take on a central theme throughout the story.

The family life and the lives of those who are connected to Sonali’s

family become interwoven along with the unfolding of the central

character’s own world of emotions. Life at school, the dance class and

the perceptions of Colombo and its horrors during the time of the second

leftist insurgency are woven around Sonali’s fears, anxieties and

doubts. Yet there is also the tranquillity of her home and family and

those connected to this environment which becomes positivisms.

Nuances of taboos

The style and outlook of Parvathi’s writing seems to call for a sense

of conservatism which appears characteristic to her writing. Matters of

a sexual nature become rather inferred rather than described directly as

a certain incident while riding the bus where it is made to understand,

a man indulges in some self-stimulating act with some exhibitionism also

being involved. But one of the more obvious instances of an evasion of

directness is when two gentleman of an academic background visit

Sonali’s house as dinner guests.

The narrative tells the reader that the closeness between the two

males was one that was bound in emotions and a made to see as a special

kind, whereby the authoress refrains from addressing the scenario as a

homosexual relationship. Perhaps the authoress felt it unsound to be too

direct with certain matters that are taboo in the mainstream. Or perhaps

she thought the nuanced and inferred descriptive seemed to carry more

room for the imagination of the reader to decide on his own.

The story begins with a narrative of a train journey and ends with

one as well. The bus travel of Sonali and the space if creates for a

‘journeying’ into the world outside observed by her as well as her

interiority.

There appears a very marked symbolism adopted by the authoress in

expressing her vision of this story as one where ‘travel’ is central to

understand the larger metaphor of ‘contrapuntal’.

One could suggest that the idea of different journeys crisscrossing

and coalescing could be meant to be seen as ‘contrapuntal’.

However, the authoress stresses through her narrative that people who

are on a perpetual traversing called life are certainly meant to keep

journeying until their final destination is found. However there is that

very unfortunate possibility that all journeys may not take the

traveller to his desired destination since not every man can

successfully become master of his own fate.

|