|

Brahms' symphony No 1:

A psychological war

by Gwen Herat from the Royal Festival Hall, Southbank

|

Danielle Muller-Scott plays the cello

|

My visits to London are never complete unless I hop across to

Southbank and listen to the London Philharmoinic Orchestra which I did

sometime ago. This time it was not the lure of Vladimir Jurowski, my

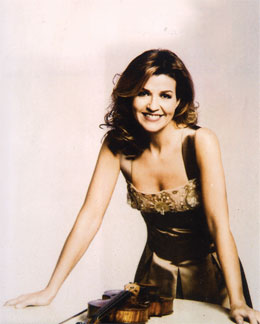

favourite conductor, but a vivacious iconic violinist by the name of

Anne-Sophie Mutter.

It is on these instances that I am furious with my father for

preventing my ambition of becoming a professional concert violinist but

instead he pushed me to the keyboard much against my will. He had the

means to send me abroad and I think I had the urge.

Few orchestral violinists can play at so many levels such as Mutter,

especially the unpredictable Brahms. She took on the Symphony No. 1

which is a psychological war, filled with successions of gripping sounds

and shapes but had no problem with the brilliant conducting by Kurt

Masur. She was ably supported by Daniel-Muller-Schott on the cello.

Freedom

The melodious freedom in the symphony was so free and fresh and the

immaculately crafted notes, were shifting and shimmering with surging

emotions. And when they came off the strings of an equally shimmering

figure, one could not ask for more. Brahms is fire; Brahms is crystal

and one has to decide which one is really he.

For me, Brahms is crystal fire when being played. In this handsome

Double Concerto, he takes us all on a sparkling symphonic upheaval. This

Concerto in A minor OP 102 scored in 1887 was first known as Double

Concerto or Brams Double. However, this is less inspired than his

earlier concertos but brimming with memorable passages and multifluous

interplay between Anne-Sophie Mutter and cellist.

This score was a peace offering to his friend, Joachim after Brahms

supported his wife in their divorce.

Interplay

|

Magnificent violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter at the Royal Festival

Hall. |

Though his Concerto No. 2 in B flat Op.83 is one of the longes almost

playing time of over forty-five minutes, and physically taxing, I still

feel this is more reflective and easy on the ear especially because of

its introduction to the beautiful third movement. Most violinists shy

away from Concerto No.2 because of the time consumed and the interplay

of the cello is limited.

Of course, one must understand that Brahms principle instrument for

scoring is the violin which needs accompanying and as far as he is

concerned, it is the cello and not the violin. Very strangely, there is

a gap of 23 years between scoring of Symphone No. 1 and Symphony No. 2.

Probably that is why the disparity.

Symphony No. 1 in C Minor Op.68

Scored in 1855-76, lustily referred to as Beethoven's Tenth Symphony

and the greated First Symphony in the history of music. Brahms wrote

this in his mid forties when he had gained confidence in himself that he

could handle symphonic form.

The Symphony is full of intensity and epic proportions which made

music lovers acclaim him as Beethoven's successor. His work contained a

striking similarity to the celebrated 'Ode to Joy' in latter's ninth

Symphony.

Brahms never stopped at Symphonies but went for piano concertos,

chamber music, sonatas and keyboard scores. They were all magnificent

and one cannot blame the London Philharmonic Orchestra opting for his

work's inclusion.

Anne-Sophie Mutter's violin rose to heights that played tribute to

the composer she selected to play for the program, confining herself to

two very popular scores of high degree.

She caressed the powerful strings with such velocity that the cello

had to move with acute speed to keep in control, without missing a

single note. There was exotic harmonising and irresistable rhythm that

formed especially in Symphony 1.

Gusto

The haunting composition had exquisite impromptus and emotionally

charged, valedictory. Mutter played with unaffected gusto and a powerful

lyrical impulse. She demonstrated a poetic sensibility rare in a

violinist.

It was so easy for conductor, Kurt Masur to manipulate her and he did

it with sheer professionalism. Danielle Muller-Scott at the cello, again

proved himself as one of the world's best that he is. With his pristine

technique augemented by deep sensivity, the cello came alive to back up

Mutter.

Violin cum cello is a tricky combination unlike the piano cum violin

but this duo made it look so simple and liquid. It stunned the audience

and to back up this iconic playing, the pair was extremely handsome,

unique in every sense.

The revered and dazzling Brahms may have stirred in his sleep. I've

seen Muller-Scott only twice but he has left a deep impression in me,

not that I am a cello fan but then the cello belongs to the string

family and that is where my heart lies.

|