|

Birds hold funerals for their dead

We have all participated in complicated ceremonies to honour a dead

person. Mind you it may be in Asia,Europe or Middle East but we have to

perform certain acts connected to the beliefs in that area.Can you

imagine funeral ceremonies or for that matter birds holding funerals for

their dead?Researchers have observed what appears to be a version of a

funeral. We have all participated in complicated ceremonies to honour a dead

person. Mind you it may be in Asia,Europe or Middle East but we have to

perform certain acts connected to the beliefs in that area.Can you

imagine funeral ceremonies or for that matter birds holding funerals for

their dead?Researchers have observed what appears to be a version of a

funeral.

Teresa Iglesias and colleagues studied the western scrub jay and

discovered that when one bird dies, the others do not just ignore the

body. Multiple jays often fly down to gather around the deceased. The

subsequent ceremony isn't quiet either. "Discovery of a dead conspecific

elicits vocalisations that are effective at attracting conspecifics,

which then also vocalise, thereby resulting in a cacophonous

aggregation," Iglesias and her team wrote. This part of the response is

similar to how the birds react when they see a predator, such as a great

horned owl. The researchers explain that "all organisms must contend

with the risk of injury or death; many animals reduce this danger by

assessing environmental cues to avoid areas of elevated risk."

The "funerals" therefore serve, at least in part, as a lesson. Since

the birds don't necessarily know what bumped off their feathered friend,

they seem to focus more on the area, associating it temporarily with

danger.The researchers noted that the living birds tended to avoid

foraging in the place where they found the deceased bird for of at least

24 hours.Prior research suggests giraffes and elephants might also hold

ceremonies for their dead. If so, perhaps there are shared factors with

humans and birds. Solidifying group togetherness and social bonding

appear to be key benefits, along with learning how to avoid (if

possible) whatever did in the deceased.

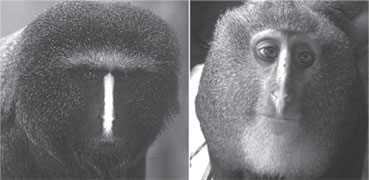

New, colourful, long-nosed monkey found

"When I first saw it, I immediately knew it was something new and

different -- I just didn't know how significant it was," said John Hart,

a veteran Congo researcher who is scientific director for the Lukuru

Wildlife Research Foundation, in Kinshasa,when his research team came

upon a shy, brightly coloured monkey species living in the lush

rainforests at the heart of the Democratic Republic of Congo,In fact,

the find was something of a happy accident. Hart first spied the suspect

monkey in 2007 while sifting through photographs brought back from a

recently concluded field expedition to a remote region of central DRC.

Yet the image that caught his eye hadn't been taken in the field. It

was snapped in a village, and showed a young girl named Georgette with a

tiny monkey that had taken a shine to the 13-year-old. Yet the image that caught his eye hadn't been taken in the field. It

was snapped in a village, and showed a young girl named Georgette with a

tiny monkey that had taken a shine to the 13-year-old.

It was a gorgeous animal, Hart said, with a blond mane and upper

chest, and a bright red patch on the lower back. "I'd never seen that on

any animal in the area, so right away I said, 'Hmmm,'" he said..Hart

through five years of field work, genetic research and anatomical study,

and a list of collaborators formally introduced to the world a new

primate species, dubbed Cercopithecus lomamiensis, and known locally as

the lesula. It turned out that the little monkey that hung around

Georgette's house had been brought to the area by the girl's uncle, who

had found it on a hunting trip. It wasn't quite a pet, but it became

known as Georgette's lesula. The young female primate passed its days

running in the yard with the dogs, foraging around the village for food,

and growing up into a monkey that belonged to a species nobody

recognised.

The lesulas live in this isolated region in groups up to five strong,

and feeds on fruit and leafy plants. The males weigh up to 15 pounds (7

kilograms), about twice the size of the females.

They also have some rather arresting anatomical features."They have

giant blue backsides," Hart said. "Bright aquamarine buttocks and

testicles. What a signal! That aquamarine blue is really a bright colour

in forest understory."

The only other monkey to share this feature is the lesula's closest

cousin -- the owl-faced monkey, a species that lives farther east. At

first it was thought the monkeys were close kin, but genetic analysis

suggests the two species split from a common ancestor about two million

years ago.Now that the new species has been formally identified, Hart

said, the next task is to save it. Although the lesula is new to

science, it is a well-established sight on the dinner table.

Courtesy Internet

|