A princess reborn and a princess redeemed

By Dilshan Boange

The second Colombo International Theatre Festival (CIFT) which saw a

host of diverse performances came alive on the boards of the auditorium

of the British School in Colombo presented theatregoers a remarkable

evening of performance on April 1 in the form of two solo acts

conceptualised on rereading two prominent female characters from two of

India’s greatest epics.

The performances

The performances were by two young ladies who were part of the

student contingent from the Flame School of Performing Arts.

|

|

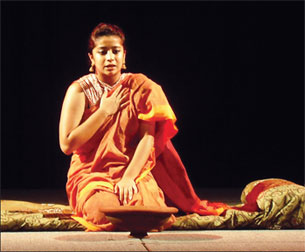

Meenakshi |

Their performances were works which they had developed as part of

their drama and theatre studies as final year students. The solo acts

were a critical review or reappraisal of how the characters Draupadi in

the Mahabharata and Shupranakha in the Ramayana have been portrayed.

The performances were about giving voice to two women whose very

being had been written entirely by the male hand of history.

The voices that were theatrically alive that evening speaking to the

viewers sitting in the gentle darkness of the auditorium was a new way

of rendering the past, made the official record called history.

It was in a way to give the female individuals their worth as

personae that have a right to be heard.

The darkness lifted as the stage came unveiled to sight under a red

light washing to the width and breadth of the performance space, washing

over the regally seated female figure garbed in white.

And then the atmosphere became ripe with anticipation as the redness

lessened and the female figure spoke.

Her opening words were that the war that erupted between the Kauravas

and the Pandavas as narrated in the Mahabharata “had to happen”.

Thus the voice of Draupadi the wife to the five Pandava princes of

the greatest Indian epic was brought to life by Devika Kamath whose

depth and firmness of tone ‘set the stage’ for a statement to be made. A

statement to be heard. To be listened to.

A princess reborn

The monologue opened with a justification to the war that engulfed

countless Kshatriyas in a horrendously bloody war as one that could not

be averted and that she Draupadi, could not be held to blame for the

lives that were lost and the blood that drenched the earth. It appeared

to me a very assertive call for self vindication from whatever blame

that had been cast on her in the Indian epic. It was an expose of sorts

of the victimisation that Draupadi had been subjected to by the

patriarchal status quo. The various incidents that were cited and

critically discussed as per the subjective outlook of a woman showed

that there was a fine line that Devika trod in her creating the voice of

a Draupadi ‘reborn’ to tell her story.

The Draupadi brought to life by Devika wasn’t meant to be a woman on

a ‘feminist rant’. She wasn’t one to denounce the entire system of the

patriarchal order and call for a complete overhauling of the system.

There was no detectable clear and unequivocal condemnation of the entire

male kind as the root of all destruction of humankind. No, the Draupadi

that came to life to tell her story although she had a clear and

unapologetic surge of indignation coming out of her on valid reasoning

that was based on the textual source was meant to be relooked at in

terms of how Draupadi was made to suffer much injustice. Injustices she

voiced as a woman as she felt they were done upon her, or were valid in

being done upon her, because of her gender.

The plea of a princess

On that line of assertions was she making a case for all womankind

and the common oppressions that women face in the face of patriarchy?

No, Draupadi didn’t purport to be a voice for universal female

emancipation. She maintained that her appeal was for recognition, to be

treated with the dignity due to her as Draupadi –a Royal princess. The

indicated stance was on that footing of being a figure who would uphold

the rightness of the hierarchical order of society. The fact that she

ends her monologue with the same words she started with –“The war in

Kurushetra had to happen” was a reassertion of how the course of

providence is not to be tampered with. The regal bearing of a Kshastriya

princess was visible throughout the act, and thus the characterisation

that was seen brought to life on stage must be noted for these

attributes to the credit of Devika.

|

|

Draupadi |

One of the most hard hitting parts of how a young nubile woman’s own

desires in that most life defining stage of choosing a partner in

marriage was denied to Draupadi even within the circuit of conservatism

and traditionalism was delivered with emphatic expression by Devika.

Although Draupadi’s father holds a ‘Swayamver’, a contest to show skills

and talents by potential suitors to claim the young lady’s hand in

marriage, the norms are that the suitor is finally chosen from the

contestants as per paternal discretion and not by the young lady for

whom the men ‘parade’ their prowess.

To the best of my knowledge a ‘Swayamver’ does not contain within its

‘institutionalism’ a right of the lady to be given in marriage to choose

her suitor at her sole discretion. The men who participate have an equal

right and an equal opportunity to contest to win her hand; and the

criterion that decides who becomes the suitor is that the most skilled,

the winner, claims the ‘prize’ –the princess, to wed.

Partner choice

Draupadi as depicted by Devika seemed to be under the impression that

she would have the sole right to choose her future husband at the

‘Swayamver’. Was that a misreading of the tradition? Or was it the

honest feeling of what ought to be from a young woman’s point of view? I

feel it is more the case of the latter, since Draupadi who was being

given the right to be heard that evening was giving voice to her own

desires and dreams.

It is interesting to note that if one may claim the solo act of

Draupadi was a feminist critique of the Indian patriarchal system that

it must be detected how Draupadi does not reject the notion of marriage

or the tradition of an arranged marriage. It was not a denouncement of

the whole system that was the cause of her displeasure but the fact that

a margin or space for her own choosing from among the choices was not to

be. It was not a complete rejection of the tradition but a critique of

its dire rigidity. In this sense Devika didn’t venture into anything

that would be sacrilegious, it must be noted, to her credit.

The universality of the mother-in-law and daughter-in-law getting

into domestic power struggles when living under the same roof is a theme

that came out strongly in the performance. Draupadi’s resentment of her

mother-in-law and her ironclad hold on her five sons who never even

think to question their mother’s word shows the frustration and

insecurity that any wife whose husband could be directed by maternal

command would be tormented by. A valid point of argument one may say

from the perspective of a woman who had to contend with the duty of

being a wife to not just one but five husbands!

The conjugal burden

On the role of Draupadi’s conjugal position as wife to five men there

was a high degree of venomous outcry by the character brought to life by

Devika. Draupadi as a woman was objectified in being made a common wife.

The discourse was clear on that contention. Being wife to five virile

warriors surely has to be a colossal task that would have its moments of

irritation to even the most forbearing of women.

One of the main woes that Draupadi’s character speaks of is that the

fulfilment of sensual needs of the five husbands took a severely

exhausting toll on her own physical being, and that her ‘conjugal duty’

was never subservient to her claimed right to decide over her body, as

to whom and when access could be granted.

Was the character of Draupadi brought to life by Devika speaking of a

woman who felt she was a sex slave? There seemed a very potent tone of

such an assertion that may have had the danger of veering into a

statement of possible blasphemy in the perceptions of an ultra

conservative viewership who would view the scenarios and status quos

depicted in the Mahabharata as sacred and beyond critical review. This

aspect discussed, in my opinion, may have the highest potential for

controversy in this work.

‘Civilised marriages’

What came out as another undeniably hard hitting argument on the part

of the indignant Draupadi was how her status as a ‘shared wife’ to not

two or even three, but five men is posited to be scrutinised for its

validity in the conventions of ‘civilisation’. Polygamy was never alien

to eastern cultures though the West frowned upon it as being not within

the norms of what is classifiable as ‘civilised’. Similarly polyandry

was an accepted conjugal arrangement in the East. But going by what was

expostulated by the character of Draupadi, polygamy was stated as

acceptable but the concept of a shared wife between brothers was not

‘civilised’. The practice of a common wife between men, a polyandrous

marriage, could only exist amongst the uncivilised was what was

declared.

Did Vedic society only approve of polygamy and frown on polyandry? I

for one am not an authority to provide an answer to this question which

kindled much curiosity in me as I wondered what could be the reason for

the denouncement of the very ‘standing’ of the conjugal arrangement

Draupadi was put in, which is a matter that is quite different to

lamenting of the burdens that are piled on her in being wife to five

men. Did Vedic society in that sense not approve of polyandry that would

unduly burden a woman’s bodily condition?

Devika’s Draupadi even said that she was made to satisfy her five

husbands one after the other irrespective of her own health conditions.

She even had to perform her conjugal duties despite debility during

menstrual bleeding. And therefore could the discourse made by the

Draupadi characterised by Devika hint about a Vedic perception about

marriage that took to account sensitivities of the woman and her bodily

conditions? Surely these are interesting points to ponder on. But

admittedly best left to be answered by the experts.

The stage set

The stage props were sparse and didn’t play on an elaborate set.

Draupadi’s space was laid out as her central ground to take her stand.

Five poles stuck on clay vase like pots surrounded Draupadi which were

of course phallic symbols to represent her five husbands; and the

‘limits’ possibly of her space to define herself? There was one such

phallic symbol that was placed at an outer distance as the odd one out.

It became the symbol to show Karna, the charioteer’s son whom Draupadi

pined for to be wife to but was denied due to the strictness of the

system she was under.

Draupadi herself was garbed in a white sari that symbolised a Brahmin

lady of tradition. A Hindi song was played over the sound system at a

certain point in the performance. Due to the language barrier, what it

was about and how it worked in the narrative I do not know. And I will

not try to pretentiously conjecture on that aspect either.

The ‘thrusts’ of the act

As a solo performance that had a significant amount of politics in

respect of reframing the moral soundness of the position Draupadi was

put into the theme and content of the work had in it an inherent allure

which any audience which knows at least the basic theme of the

Mahabharata would find interesting. This interest of course may not

necessarily be through touching audience pulses that would be enchanting

to the ear. The ripeness for contention that could ‘tread on nerves’ is

also a limb that plays as a force that compels the attention of the

audience.

Draupadi as per the Mahabharata is a feminine and possibly docile

character I will assume. But Devika’s Draupadi in that sense was a woman

reborn. The tone and bearing that the young actress showed on stage made

a statement to that effect. There was a certain staidness in her

demeanour that was undeniably coupled with a latent indignation that was

sensible at the outset. If that was what Devika intended to project

through her characterisation then she was successful in her endeavour.

There was an undeniable assertiveness of a woman who was to speak her

mind unafraid; but yet hadn’t completely lost her ability to recall and

relive her girlishness. Devika’s acting must be noted for projecting

those attributes of the Draupadi she gave life to.

Draupadi justified

The tone of voice, the expressiveness of gesticulations and movement,

the overall persona that occupied the stage did say that the Devika’s

Draupadi had to a great a certain sense of masculinity that subtly

commanded the inner being and purpose. Whatever floweriness and ‘rose

petal softness’ that was seen in that character was more the

‘constructed’ layer of the persona than the indignant unapologetic

princess whose voice was not so much one of rebellion but of a clear

battle cry. Had Devika appropriated the character of Draupadi and

rendered according to her subjective interpretation to do her justice?

It is possible that that could have been her artistic vision.

A vision which also gained life on the boards convincingly.

Shupranakha takes the stage

The second solo act that was performed had a more distinct relevance

to Sri Lankan cultural perceptions due to the source from which it was

developed –the Ramayana. The beloved sister of the mighty king Ravana is

known by several names. In Sinhala she is called ‘Supurnika’ in the

South Indian tradition of the story she is called ‘Meenakshi’ and in the

Valmiki Ramayana which is deemed to be the standard authoritative text

she is called ‘Shupranakha’.

The Ramayana can be construed in many ways for the manifold

perspectives in which it is seen by people from both sides of the Palk

Strait. The Ramayana holds not just a record of geopolitics but a sacred

narrative, a holy text for Hindus who find in it much inspiration as

well as religious doctrines.

But what the talented young Swati Simha brought to life on stage to

the audience seated in the gentle darkness was a bold artistic statement

that critiqued the established discourse of the Valmiki Ramayana to

redeem the dignity a woman wronged.

The performance opened with an English translation of a Hindi poem

being read to the audience over the sound system. The words spoke

disparagingly of Shupranakha and demonised her while Prince Rama was

glorified as per the discourse of the Ramayana of the sage Valmiki. The

verse is then played over the sound system as a song and the character

of Shupranakha enters the stage dancing to it. What could that movement

to the rhythm of a song that does not dignify Shupranakha symbolise? It

may be rendered as a symbolic opening observing total deference to the

established discourse, the unchallenged status quo. She dances to the

‘tune’ history had set for her.

Harmony breaks

A complete devastation of the ‘harmony’ of song and dance then occurs

as the first oral element enters the narrative –a piercing scream.

Shupranakha holds her hands before her nose. The heartless act of her

defacement, her mutilation at the hands of Prince Lakshman has happened.

That is how the Ramayana makes her memorable. The ‘Rakshasi’ whose

nose was cut off by a virtuous man. But what follows that very instant

is something surprising. No there is no lamentation. History it seems

has not weighed down on this Shupranakha whose next oral output is a

laugh. She laughs off what history has accorded her. This juxtaposition

of a scream and a laugh that happens in quick succession, within

seconds, is a powerful symbolic depiction of how history is divorced

from the present on the stage through the Shupranakha who speaks

unyielding to the textual directive of the Ramayana. And with no

uncertain terms the character on stage asserts that history had done her

no favour, no justice and denounces its credibility as being after all,

“his-story”. The narrative written by the hand of a man.

‘Meenakshi’ gains presence

With expressive eyes and feminine facial nuances the character begins

her verbal discourse from the point of where identities find their most

basic footing –a name. Shupranakha when translated of its etymological

composite means one with ‘long fingernails’. She contests the validity

of this assertion in the Ramayana, this christening given her by the

ancient Indian text. Would parents name their children with such

unflattering names she asks the audience, and explains how her name

given at birth, the chief source to this claim being as I believe the

Ramayana authored by Kamban, was Meenakshi, which translates as ‘fish

like eyes’. This hint at how the two versions of the Ramayana authored

by Valmiki and Kamban have notable discrepancies and disagreements about

the character of King Ravana’s sister indicate that the texts carry a

notable set of politics which perhaps relates to the North-South clash

which has been going on since time immemorial in the subcontinent.

The Ramayana’s chief female character is Sita Devi, the wife of

Prince Rama. But the war that erupted between the forces of Prince Rama

and King Ravana has at its root the matter of a vendetta which goes very

underplayed in the general synopsis of the Ramayana even as per Sri

Lankan conceptions, which is nothing other than the mutilation of

Meenakshi which causes her mighty brother to avenge the insult done to

his sister by abducting the wife of the offender. How do we then ‘read’

Meenakshi today?

Meenakshi unfolds

The unfolding of the character of Meenakshi as performed by Swati

showed a female who was explained in ways that were both rooted in the

textual source of the Ramayana as well as interpreted somewhat

subjectively on the basis of female sensibilities perfectly acceptable

to present society. The state of Meenakshi as a widow, whose husband

tried to challenge the King of Lanka and then paid for his foolishness

with his life, is spoken by Swati’s Meenakshi as a matter that is not

reviled by a widow but more as an inevitability to which the blame would

be on the obvious transgressor. Meenakshi’s decision to go into a form

of voluntary seclusion in South India which was ruled by her brother, to

recover from the pain of losing her husband shows a woman who was in

search of solitude to heal within. It also created the pathway to

ideological confrontations as revealed latterly.

The admiration of her brother Ravana and his mightiness and how she

was as a woman allowed greater status in their society showed Swati’s

Meenakshi to be a woman of much fraternal loyalties and affection as

well as being insightful as to how their society differed from that of

the patriarchal Hindu society of Prince Rama. A great deal of insight is

thus offered by the discourse performed on stage of what differences of

ideologies of the two civilisation would have existed based on the

matter of the status of females in their respective social hierarchies.

An unacceptable boldness

Her boldness in interacting with Princes Rama and his younger brother

Lakshman were seen to be improper and perhaps even somewhat impudent by

Lakshman indicates Swati’s Meenakshi. She reveals that she tried to,

through her interactions with Sita, instil in the latter some sense of

independent thinking, some critical reasoning.

Lakshman becomes angered over her intervention to spur some critical

thinking in Sita, says the solo performer, and that can be interpreted

as an attempt by Meenakshi, a woman, to be ‘political’ in that instance.

She believed she was helping Sita find some sensibility to her thinking.

This was of course not acceptable to the rigid patriarchal Aryan outlook

which she sought to upset. And for that she paid a severe price. The

humiliation of her nose being cut off by Lakshman.

The Valmiki Ramayana’s Shupranakha, is a hideous she-demon who falls

in love with Prince Rama who is the epitome of masculine beauty, and

then tries to attack the beautiful Sita whom she envies for the fortune

of being the wife of the man whom she covets. Interestingly Swati’s

Meenakshi plays a line that doesn’t negate that entire story outline.

Swati’s Meenakshi admits that she was hopelessly in love with Prince

Rama, yet didn’t attack Sita but sought to befriend her. An act in

search of propinquity to the one you pine for, one may say. Swati’s

Meenakshi describes her first moment of beholding the sight of Prince

Rama. And it must be noted at no point does she demean the persona

deemed to be by Hindu belief a divine incarnation.

Rama adored

The glow of his skin and sinewy limbs all speak of rapture by a woman

mesmerised to a figure who epitomises refined masculine beauty.

Enamoured with Prince Rama the description was by a woman who was madly

in love. By my reasoning the level of ‘femininity’ of a female can be

gauged, assessed on the one hand by the way she reveals or explains the

feeling of her experience of falling in love with a man. It is that

unhidden sincerity of how she feels within of being in love that

bespeaks a deep and warm femininity.

The Meenakshi brought to life by Swati had a sentimental femininity

that reached its most mellow point in describing what she felt for Rama.

That point of the narrative in my opinion is the winning ticket that

speaks to the sentimentalities of an audience to bring empathy on to her

side. A very intelligently and tactfully crafted portrayal of a woman

wronged by history now seeking redemption, one may note.

Restoring femininity

The Meenakshi brought to life by Swati also says that Prince Rama

enjoyed her company and her personality. Thereby one may infer that this

‘rereading’ of Meenakshi was to restore her femininity as both within

and outwardly. In the performance by Swati, Meenakshi had been a woman

who was desirable to Prince Rama in at least a platonic way.

The masculine beauty of Prince Rama is in no way contested while the

femininely appealing qualities of Meenakshi are also accorded her. A

moderate view had been at work in the crafting of this character and the

contextualisation needed to drive forth the objective of Swati’s

Meenakshi.

Amongst the critically challenged notions as per the established

discourses on what constitute good and evil, Swati’s Meenakshi brings

two very interesting topics to the stage. One is what is pure as against

impure? Sita is the symbol of purity and virtue while Shupranakha would

be an embodiment of impureness. Another is the theme of light and

darkness. Sita would be light or illumination while Shupranakha would be

darkness. Positivity versus negativity one may say.

A simile for pureness

Swati’s Meenakshi brings the following arguments on the boards.

Sita’s purity is likened to the water that may be got from a melting

iceberg. Pure and devoid of any sediment. A pureness that would lack any

taste. Possessing no ‘character’ of its own.

It is the sediment argues the Meenakshi on stage that creates tastes

in the water; that gives it character. Creating flavours as sourness,

bitterness and also sweetness one may say. Was she in a way giving as a

subtext, between the lines spoken, an equation for the audience to work

on? That the lack of any character renders one dull? Pureness, in its

absoluteness equals dullness?

Swati’s Meenakshi certainly showed in unflattering mimicry the

responses Sita gave her when she asked her things such as what she

thinks of her position as a wife. Puppet like robotic gestures and

monotonously intoned answers that quote lines from the Vedic scriptures

of what the wife would be in relation to the husband; that is what she

portrays as the sensibility of Sita. What can Prince Rama find beguiling

in such a woman with no intelligence of her own? That question weighs

heavily on Meenakshi’s mind and torments her.

What is purity?

What then is ‘purity’ as Swati’s Meenakshi sees it? Though she

doesn’t venture to give frameworks of her own to establish a meaning for

it conceptually, with very emotive expression Swati’s Meenakshi declares

that what she felt for Rama was pure. It was a love that was true and

sincere, and undiluted.

That she claims to be the pureness that was in her. Her love for

Rama. The idea of loving Rama as a truth of emotions could be a form of

purity. Her love for him was fulsome and not diluted with doubt. A

pureness by her reasoning which sadly for her, didn’t merit the

recognition of being the purity that is valued as ‘virtue’ in the annals

of history.

What is ‘light’? Is it merely the absence of darkness? This is the

other matter Swati’s Meenakshi puts forward in her discourse. If light

is merely the absence of darkness then one may contend that light is the

creation while darkness is what exists in the world. Is darkness then

possibly interpretable as infinite and eternal? These contentions

brought out by Swati’s Meenakshi showed her to be one who didn’t believe

in the black and white binary opposition theorems. She was asserting

that she was a woman with a mind of her own.

Aspects of visage and acting

Some of the notable aspects of the appearance of the character were

that her dress was notably of a Dravidian motif. Swati was very dynamic

in her switch of pulse to the different moods of her character of

Meenakshi; effortlessly making transitions that were mercurial yet quick

at regaining solidity.

Her tones and facial expressions brought out a great depth of the

character portrayed. A lithely spark was visible in her acting and Swati

was more comfortable with the stage space being open to show she isn’t

bound to its demarcated spaces alone; the example being how she used the

steps to the stage to sit on. The character of Draupadi portrayed by

Devika on the other hand appeared in her movements to be one who is more

directed and framed to a demarcated space. The manner in which stage

space is used could reflect the nature of the two characters as women.

Draupadi is more constrained in her world. Meenakshi is a more free

spirited soul.

A woman redeemed

The performance ends with an element that works with an overt dual

play in the representations it makes. A verse, a poem in rhyming

couplets is recited by Swati’s Meenakshi. The lyrical, or word content

speak of devotion to Rama. “Rama is right Rama is our guiding light” she

says. The words are in complete conformity with the established

discourse and offers submission to the divine incarnation that is Rama.

The tone however denoted sarcasm and was complemented with nuanced

facial expressions. That element of the verse recited with hands

together in obeisance showed innovation which ‘word wise’ contained what

is orthodox –the praise of Rama, while giving its ‘casing’, the ‘tone’,

the means to project what is within the woman who was wronged. The woman

regaining herself and her redemption from history. Setting the stage for

the final moment Swati’s Meenakshi comes forward to sit on the steps to

the stage, and says that despite the injustice history has done to her,

despite the distortions, that evening, she had won the argument.

And the smile of complacence she bears speaks of her inner

satisfaction. A satisfaction that is true, free of dilutions, or doubts.

|