Did humans come from the seas instead of the trees?

Scientists, academics and medics will gather in London to discuss a

topic that has been virtually unmentionable in academic circles for

decades: are humans descended from "aquatic apes" that spent more time

swimming than dragging their knuckles on the ground?

The last time this question was asked, at a conference in 1992, there

was much scoffing and ridicule. Other academics sneered and Bernard

Levin wrote a full-page article lampooning the idea.

This week's conference, Human Evolution Past, Present and Future -

Anthropological, Medical and Nutritional Considerations, at the Grange

St Paul's Hotel, has also already been the subject of much derision.

Followers of the conventional and overwhelmingly accepted belief that

our ancestors were very much land-based are launching a parody campaign

online to argue we evolved from "space monkeys". Most scientists will

openly scoff at the idea of us deriving from water-bound primates. This week's conference, Human Evolution Past, Present and Future -

Anthropological, Medical and Nutritional Considerations, at the Grange

St Paul's Hotel, has also already been the subject of much derision.

Followers of the conventional and overwhelmingly accepted belief that

our ancestors were very much land-based are launching a parody campaign

online to argue we evolved from "space monkeys". Most scientists will

openly scoff at the idea of us deriving from water-bound primates.

But, perhaps emboldened by the presence of Sir David Attenborough -

who was booked to attend the conference for one session but asked at the

last minute if he could attend both days - the aquatic ape theorists are

back.

The conference is chaired by Professor Rhys Evans, an ear, nose and

throat surgeon at the Royal Marsden Hospital, who is candid about the

scope of the conference. "We are trying to discuss the pros and cons of

the theory," he said. "But many of the things which are unique to humans

- such as a descended larynx, walking upright, fat beneath the skin, and

most obviously an extremely large brain - it seems can best be accounted

for as adaptations to extended periods in an aquatic environment." The

original aquatic ape theory, developed by Sir Alister Hardy and made

public in 1960, posited that a population of early humans, or hominoids,

was isolated during tectonic upheaval in a flooded forest environment,

similar to that of parts of the Amazon. Our ancestors, it was argued,

either adapted to water - and climbing in trees - or died out. Over many

generations, mutations that made swimming and diving easier reproduced

in the population at the expense of the more traditional, water-averse

ape genes.

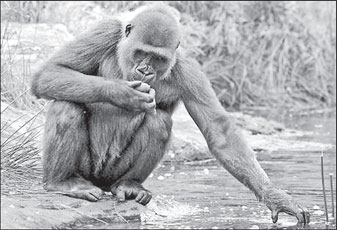

Modern-day apes do not like water. In zoos all around the world, apes

are contained by moats of water. Even wadeable moats are sufficient: if

you drop a baby orangutan into water, it sinks like a stone. A human

baby, however, will close its larynx and automatically paddle its arms

and legs, giving you a few precious seconds to retrieve it.

The aquatic ape theory would explain this ability - unlike the

traditional savannah theory of human evolution. Widely accepted wisdom

states that when humans came out of the woods and on to the savannah,

walking upright gave them an increased field of vision and freed up

hands to use tools.

Bipedalsim also exposed less of the human body to the harsh sun and

humans shed hair and increased sweat production to cope with the heat.

But, the aquatic ape proponents point out, deer and antelope kept

their fur and their quadrapedal ways on the savannah. Our copious salty

sweat production, and water consumption requirements, they argue, are

far more indicative of life in the water. And lions co-operate in

hunting without evolving significantly larger brains than other cats.

The key ingredients for growing a large brain, according to Professor

Michael Crawford, from Imperial College London, are found in fish. "DHA,

or Docosahexaenoic Acid, is essential for developing brain tissue, and

in order for our brains to grow to the size we have now, our ancestors

must have had to eat a lot of fish."

This would have taken place over many hundreds of thousands if not

millions of years, and is part of the reason that the aquatic ape theory

has evolved since its last incarnation, into, tentatively, the waterside

theory.

"Molluscs, crabs and snails would be available in abundance in

coastal regions, flooded or swamp forests, lagoons and wetlands,"

Professor Evans said. "Such lifestyles, climbing and hanging vertically,

grasping branches above the water, wading on two legs, floating

vertically collecting foods amid floating vegetation - might help

explain hominoid body enlargement, tail loss, vertical spine, dorsal

shoulder blades, wide thorax and pelvis, great ape tool use and

thickening of enamel."

So waterside theorists are now proposing a prolonged exposure and

adaptation towards coastal living, stretching over several million

years. They argue that fossil evidence seems to back this up.

- The Independent

|