The enigmatic Kafka and his continuing influence

Part 1 Part 1

Recently, I was invited as the keynote speaker at a conference on

Asian cinema held in Germany. Before the conference, I toured many

adjacent countries including Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary and

Slovakia. It is evident that a powerful sense of history figures

prominently in the experience in all these countries inflecting all

facets of their being. In Prague I was able to stand in front of the

house where the acclaimed writer Franz Kafka was born and soak in the

atmosphere.

Museums and monuments dedicated to his memory are aplenty and Prague

is indeed the city of Kafka. Memories of his writings, his troubling

images, came flooding in. This had the effect of turning my thoughts

towards Kafka and what he means to us today.

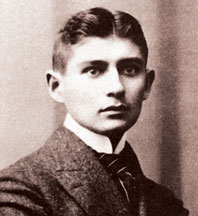

Franz Kafka, unquestionably, is one of the greatest writers of the

twentieth century. He is also one of the most enigmatic. He has had a

profound impact on the growth of modern literatures in the East and the

West. His writings compel us to re-examine the notions of alienation,

disenchantment, the absurd, guilt, self-censure with fresh eyes. Many of

his stories speak in the voice of the uneasy age.

Franz Kafka |

Distinguished writers and critics such as, Albert Camus, Elias

Canetti, Milan Kundera, Jacques Derrida., W.H. Auden, George Steiner,

and Harold Bloom have extolled his indubitable virtues in glowing terms.

To my mind, there are a number of important traits in his writings that

serve to advance the claim that he is one of the most consequential

writers of the past century. Let me focus on a few of them.

Kafka, it seems to me, was able, in his fictional writings, to

capture the anxieties and worries of the period in which he lived with

remarkable power and cogency. He located himself in the extremes of his

consciousness to uncover important facets of existential reality. He

succeeded in reaching the deepest currents of European predicaments as a

sensitive writer. W.H. Auden, commenting on Kafka’s writings, makes the

observation that ‘had one to name an author who comes nearest to bearing

the same kind of relation to our age as Dante, Shakespeare and Goethe

bore to theirs, Kafka is the first one would think of.’ And Paul Claudel

proclaimed ‘besides Racine, who is for me the greatest writer, there is

one other – Franz Kafka.’

A feature of Kafka’s writings that has stirred the deepest interest

of many writers and critics is his uncanny clairvoyance, his ability to

feel the darkness that was to engulf the world through fascism and

autocratic rule. Many of his works of fiction point in this direction.

As George Steiner remarked, ‘Kafka’s nightmare-vision may well have

derived from private hurts and neurosis. But that does not diminish its

uncanny relevance, the proof it gives of the great artiste’s possession

of antennae which reach beyond the rim of the present and make darkness

visible.’

As Steiner emphatically proclaimed, ‘the key factor about Kafka is

that he was possessed of a fearful premonition that he saw, to the point

of exact detail, the horror gathering.’

He maintains that his novel manifests the classic model of the terror

state. It foreshadows the furtive sadism, the panic which totalitarian

states insinuate into the private lives of people. As Steiner went on to

argue. ‘Since Kafka wrote, the night knock has come on innumerable

doors, and the name of those dragged off to die like a dog, is legion.

It is Steiner’s conviction that Kafka prophesied that actual forms of

the calamities of western humanism that Nietzsche and Kierkegaard had,

was ‘seen like an uncertain blackness on the horizon.’ And the German

philosopher Hannah Arendt said that Kafka’s nightmare of a world has

actually come to pass.

Another important feature of Kafka’s writing is his distinctive

imagination that infuses his work with a rare vividness and power to

shock.

His fellow-countryman Milan Kundera said ‘the slumbering imagination

of the nineteenth century was abruptly awakened by Franz Kafka, who

achieved what the surrealists later called for but never themselves

really accomplished; the fusion of dream and reality.’ Kundera goes on

to assert that this was indeed a long-standing ambition of novelists as

intimated by writers such as Novalis.

However, its fulfillment necessitated a distinctive blending that

Kafka alone discovered a century later. It is Kundera’s conviction that

Kafka’s tremendous contribution is less the last step in a historical

evolution than an unanticipated opening that demonstrates the fact that

the novel is a site where the imagination can explode as in a dream.

A careful reader of Kafka’s works surely would realise that he

attaches a great significance – a negative significance, to be accurate

– to the idea of institutions in modern societies. They are palpable,

menacing and inescapable. Milan Kundera expresses the view that

novelists before Kafka frequently exposed institutions as zones where

antipathies and conflicts between diverse personal and public interests

were played out.

In Kafka, however, it is evident that the institution is a mechanism

that adheres to its own laws. As he says, ‘no one knows now who

programmed those laws or when; they have nothing to do with human

concerns and are thus unintelligible.’

They are certainly unintelligible’ but at the same time we sense that

there is a dark logic working through them that makes these institutions

all the more menacing.There is, in Kafka’s writings, a curious logic at

work - a logic that seems to invert the normal logic we live by. The

dark and anxiety-provoking world created by him is inextricably linked

with this inverted logic.

Again, Kundera has something perceptive to say on the matter. He

claims that there is a reversal of the ideas of guilt and punishment in

Kafka’s fiction.

In his narratives, the person being punished whether he is the

protagonist in The Trial or The Castle,does not know the reason for the

punishment. The punishment is patently absurd and unfair; so much so

that to find peace and solace he has to find a justification for his

penalty.

As Kundera says, ‘the punishment seeks the offence.’

Kundera comments on this phenomenon with accuracy. ‘The Prague

engineer is punished by intensive police surveillance. This punishment

demands the crime that was not committed, and the engineer accused of

emigrating ends up emigrating, in fact, the punishment has finally found

the offence.

Not knowing what the charges against him are, Kafka decides, in

Chapter Seven of the trial, to examine his whole life, his entire past

down to the smallest details. The ‘auto-culpabalisation’ machine goes

into motion. The accused seeks his offence.’ The complex and bizarre

relationship between crime and punishment gives Kafka’s writing its

distinctive texture

to be continued

|