Tagore as a factor in Indian cinema

Rabindranath Tagore influenced many facets of Indian culture ranging

from literature and painting to music and cinema. In the next few

columns I wish to focus on Tagore’s influence on Indian cinema in

relation to the work of a relatively young Bengali filmmaker who

unfortunately died at an early age. Rabindranath Tagore influenced many facets of Indian culture ranging

from literature and painting to music and cinema. In the next few

columns I wish to focus on Tagore’s influence on Indian cinema in

relation to the work of a relatively young Bengali filmmaker who

unfortunately died at an early age.

The filmmaker I have in mind is Rituparno Ghosh. Rituparno Ghosh was

one of the most talented and perceptive of Bengali film directors (1963-

2013). His death at the comparatively young age of forty nine years was

indeed a great loss to Indian cinema in general.

He is the author of a significant body of work that includes films

such as Hirer Angti (1992), Unishe April (1994), Dahan (1997), Asukh

(1999) Barwali ( 20000), Ustab (2000), Titli (2002), 2003 Chokher Bali

(2003), Antar Mahal (2005) and Abohoman (2009). Most of his films are in

Bengali, but he also made films in Hindi and English. A central theme,

it seems to me, runs through his work and guided his imagination - the

quest for human freedom. He was always concerned about the lack of

freedom that characterized the lives of women in India and elsewhere and

later he began to explore issues of homosexual relations and transgender

desires as articulations and effects of freedom. In this short essay, I

wish to explore Ghosh’s pursuit of freedom in relation to his film

Chokher Bali: A Passion Play.

|

|

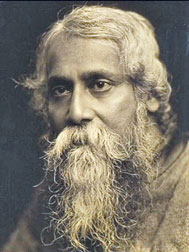

Rabindranath Tagore |

Novel

Chokher Bali is based on a novel by the Nobel Prize winning Indian

writer, Rabindranath Tagore. Rituparno Ghosh was deeply attracted to

Tagore; His films such as Chokher Bali, Noukadubi, Chitrangada are based

on Rabindranath Tagore’s writings. In Ghosh’s film Asukh one discerns

the distinct influence of Tagore.

In addition, Ghosh made a documentary on the life and work of Tagore

titled Jiban Smriti. Moreover, in his films, at appropriate moments, he

employed popular songs and the distinctive music (Rabindra sangeet) that

Tagore fashioned. Ghosh believes that Tagore’s works need to be read

dissected, reinterpreted and assimilated by each generation in the quest

for its own social and artistic truths. He had a great empathy for

Tagore; he said that Tagore’s life was ‘a journey of a lonely traveller’

and this can equally well be said of Ghosh’s relatively short life.

Humanism

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) was unquestionably one of the

greatest Indian writers and artists of the twentieth century. His

indubitable talents moved in different directions enriching diverse

fields of artistic endeavor. He distinguished himself as a poet,

lyricist, novelist, short story writer, playwright, painter, musician,

educator and social thinker. The idea of humanism is central to Tagore’s

work, and this is closely intertwined with the quest of freedom. This is

indeed a desire that marks Rituparno’ Ghosh’s work; after all, Ghosh is

a great admirer of Tagore.

The term humanism carries a multiplicity of meanings that aims to

highlight the centrality of the action of human beings, their thoughts

and actions, their freedom and sense of agency. This term, however, has

been disseminated throughout the world as a European concept that has

been invested with a universal validity. The important point about

Rabindranath Tagore’s humanism, and that of Ghosh, is that it focuses on

the idea that humanism is not one thing but many, and that it is

imperative that we seek to pluralise this concept. The work of Tagore

and Ghosh enable us to move forward in this endeavor. In recent times,

the term humanism has taken on the force of a smear-word in academic

polemics in the west; indeed, it has been reduced s reactionary ideology

largely due to the influence of such newer modes of inquiry such as

post-structuralism and pot-modernism. It seems to be that the efforts of

Rabindranath Tagore and Rituparno Ghosh facilitate a re-consideration of

some of the charges levied against humanism by contemporary

commentators.

There are, to my mind, three central charges brought against humanism

by modern critics. First, humanism is regarded as a form of ideology

that serves to de-contextualise some of the ideas and values associated

with the Renaissance in Europe and to freeze them into a kind of

universality. Second, humanism is placed at the centre of interests and

agendas of the sovereign and atomists individual who is seen as

self-present and originator of action and meaning, the privileged locus

of values and civilisational achievements.

Different picture

However, the humanism articulated in Tagore and Ghosh presents a

different picture. They were interested not in an atomistic individual

but the individual in relationality, the individual as a part of a

collectivity, as an adjunct of a larger reality.

Third, it has often been commented on by theorists like Michel

Foucault that humanism should be mapped not as a free-floating and

timeless entity but as a human creation that bears the distinctive

imprint of specific discursive formations.

This line of thinking has a direct bearing on the way that human was

perceived and advanced by Tagore and Ghosh. It has to be asserted that

far from promoting a free-floating and timeless concept, the humanism

that guided Tagore and Ghosh was firmly tethered to the culture and

traditions and values that nourished them.

Tagore’s humanism was intimately linked to the idea of freedom as was

Ghosh’s. Tagore approached the idea of freedom in its manifold

complexity. For him, as for the British philosopher Isaiah Berlin,

freedom was both positive and negative. Negative freedom was the escape

from bondage while positive freedom was reaching out towards creativity

and self-fulfillment.

Both Tagore and Ghosh understood freedom in social, cultural,

political, metaphysical and artistic terms. For example, statements such

as the following made by Tagore, make clear the relationship between

freedom and the wider social discourses. ‘Those people who have got

their political freedom are not necessarily free, they are merely

powerful. The passions which are unbridled in them are creating huge

organizations of slavery in the guise of freedom.’

Tagore, like Ghosh, was interested in the metaphysical dimensions of

freedom. In his poetry, more specifically in his nature poetry, one

observes how he is straining to reach a higher freedom, unconstrained by

worldly bonds and signifying a unity with the ultimate reality

reminiscent of the Upanishads. Tagore’s poetry, I contend, bears the

weight of this desire. Freedom was for him a creative force and humanism

finds its fullest articulation in freedom.

As Tagore once observed, ‘our mind does not gain true freedom by

acquiring materials for knowledge and possessing other people’s ideas

but by forming its own standards of judgment and producing its own

thoughts’. Hence, the independence of outlook is a significant strand in

the fabric of Tagore’s humanism.

I have chosen to discuss Tagore’s idea of freedom and humanism for

two reasons. First, Rituparno Ghosh, by his own admission, was a great

admirer of Tagore. Second, the ideas of freedom and humanism espoused by

Tagore find a ready echo in Ghosh’s work and enable us to construct a

productive frame of intelligibility to approach his cinematic output.

What we find in Ghosh’s work is a sustained attempt to explore and

cinematically enact the relentless quest for human freedom. Human

freedom is vitally connected to full citizenship and this is an idea

that finds repeated expression in Ghosh’s work.

Novel

Let us now consider Ghosh’s film Chokher Bali against this backdrop

of thinking. This film is, as I stated earlier, based on Rabindranath

Tagore’s novel. This novel has been translated into English under the

title Binodini. (This was indeed the first title that Tagore gave to

this novel before changing into Chokher Bali). The story of the novel

and the film can be encapsulated as follows. Binodini is a young,

beautiful, educated woman who finds herself as a widow after her husband

des a few months following the wedding. She returns to her village and

lives for a short time there. One day, she encounters one of her

relatives, and after some discussion, agree that it is best for Binodini

to come and live with the woman and her son Mahendra.

Proposal to marry

Mahendra had, of course, earlier turned down a proposal to marry

Binodini. Mahendra is now married to Ashalata, and apparently they are

deeply attached to each other, However, after the arrival of Binodini in

the house, things begin to change; Mahendra clearly is attracted to

Binodini and loses interest in Ashalata. Meantime, Binodini is

interested in Bahri, the adopted son. It is this emotional relationship

between Binodini, Mahendra, Bahri and Ashalata that constitutes the

essence of the story.

In Choker Bali, as in many other works such as Ghare Baire and Char

Adhyay , Tagore is concerned with the plight of Indian women, their lack

of freedom. Similarly in many of Rituparno’s films such as Titlti,

Baharwali, Antar Mahal and Ustav . we find Ghosh focusing on the

predicaments of women; their lack of freedom was a source of great

consternation to him. And his later films, he extended this quest for

freedom to include the plights and predicaments associated with

homosexuality and transgender desires. In seems to me that the optic of

human freedom is a most appropriate lens through which to examine

Rituparno Ghosh’s cinematic work.

Chokher Bali is obviously based on Tagore’s novel of the same name.

However, there are certain differences that one can observe in Rituparno

Ghosh’s film. In this regard, I wish to highlight six of them. First,

Binodini is presented as a kind of rebellious character in Tagore’s

novel. This fact is heightened, accentuated in Ghosh’s film. The

protagonist of the film comes across as being far more aggressively

independent-mined in Ghosh’s film than in Tagore’s novel.

She makes use of her widowhood as a site for acquisition of agency

and encourages other widows to ignore long-standing taboos such as

abstaining from drinking tea. This is an intentional move on the part of

Ghosh as a filmmaker to underline the plight of women and the compelling

need for acquisition of agency. Second, in the film there is a greater

emphasis on physical intimacy, physical aggressiveness; in a ay, this

move serves to further highlight and to call attention to the miserable

state in women in India find themselves. Rituparno Ghosh’s camera, which

is reflexively eloquent for the most part, captures this aspect well.

Eroticism

Third, in Ghosh’s film there is a great measure of eroticism infusing

the relationship of the characters in Rabindranath Tagore’s novel, for

example the relationship between Binodini and Mahendra is marked by a

muted eroticism. In the case of Rituparno Ghosh’s film, it is much more

pronounced and is central to the meaning of the film.

At times, unlike in the book, Binodini initiates the currents of

eroticism. An aspect of Ghosh’s cinematic art is the construct of dense

visual registers in which simultaneously multiple layers of meaning are

in play. For example the relationships between Binodini and Mahendra are

inscribed with this density of meaning with the result that while

eroticism is reconfigured prominently, there are other countervailing

forces at work such as the invocations of death.

In many scenes, in fact, there is a remarkable juxtaposition of

eroticism and death. It is not the juxtaposition of eroticism (eros) and

death (thanatos) that Sigmund Freud posited but something slightly

different which has a bearing on Indian culture.

Fourth, the idea of self-articulation is important in the film. In

Tagore’s novel, the need for female agency is fully endorsed and indeed

constitutes a vital facet of the theme. In Ghosh’s film, however, this

is given greater weight and visibility. Passages in the novel which are

given over to authorial observation are invested with a far greater

measure of self-articulation in the film. This self-articulation is not

merely a question of verbal expression; far more, importantly it relates

to the way in which Rituparno Ghosh has chosen to construct his visual

registers. The juxtapositions, the framings, the camera angles and

placements, the diegetic soundtrack all contribute to this effect.

Use of space

Fifth Rituaparno Ghosh’s use of space deserves careful consideration.

Space is indeed a crucial aspect of Ghosh’s meaning. Short descriptive

passes in the novel are converted by the filmmaker into various spatial

configurations pregnant with meaning. Let us consider two representative

passages from the novel.

‘ Though Binodini lived in the same house that she had not yet

appeared before Mahendra. But Bihari had seen her and knew that such a

girl could not possibly be condemned to spend her days in a wilderness.

He also knew that the same flame that lights a home can burn it down.

Mahendra teased Bihari for his obvious concern for Binodini and thought

Bihari met this raillery with light-hearted repartees, he was worried in

his mind , for he knew that Binodini was not a girl to be either trifled

with or ignored.’

Binodini was constantly luring him on and yet would not let him come

near her even for a moment. He had already lost one boast – that he was

invulnerable. Must he now lose face altogether and confess that he was

incapable of winning another heart, however much he tried. to be

conquered without making a conquest in return – this defeat on both the

fronts was very galling to Mahendra’s self-esteem…’

The emotional content of these passages are converted into a series

of wonderful images by Ghosh in the film. The idea of spatiality is

central to this effort. Rituparno Ghosh is a filmmaker who sets great

store by the idea of cinematic space and he has a remarkable knack for

turning physical space into cinematic space. To turn physical space into

cinematic soave involves the careful manipulation of space, to invest it

with newer human meanings. Ghosh has a way of giving his visualities

densities of meaning by deft use of cinematic space. For example, his

cinematic space is not unitary but plural in that there are diversities

of meaning. To give one example, he selects visual details carefully not

only to attain verisimilitude, which clearly is one of his aims, but

also to disrupt the unitary meaning.

To be continued |